Sasha Zbrozek is a homeowner in Los Altos Hills who is proposing a 20-unit development using the builder’s remedy.

Jim Gensheimer/Special to The ChronicleLos Altos Hills resident Sasha Zbrozek is the first to admit that he is not a real estate developer.

“I’m just some random homeowner dude,” he said. “I’m not qualified to develop much.”

Yet, over the last few days, Zbrozek has become the face of the so-called “builder’s remedy,” a fledgling movement that over the next year could transform the way that housing development is approved across the Bay Area.

The builder’s remedy allows property owners to bypass most local planning and zoning rules if that city or county has failed to complete certification of a state-mandated eight-year housing plan known as a “housing element.” So far, the Bay Area is not doing too well: Only five of 109 jurisdictions had their housing plans approved by the state by the Jan. 31 deadline. That means that all of Marin County, most of the South Bay — including San Jose — and most of the East Bay are subject to the builder’s remedy. Among large cities, only San Francisco is in compliance.

But fears that the builder’s remedy would prompt an army of big-city developers to stick highrise condos in the middle of leafy suburban neighborhoods so far have not come to fruition. Only a handful of property owners — there are two projects in Los Altos — have filed builder remedy applications. And, so far, the proposals have been modest and have involved frustrated small property owners or fed-up homeowners like Zbrozek, rather than well-funded corporations.

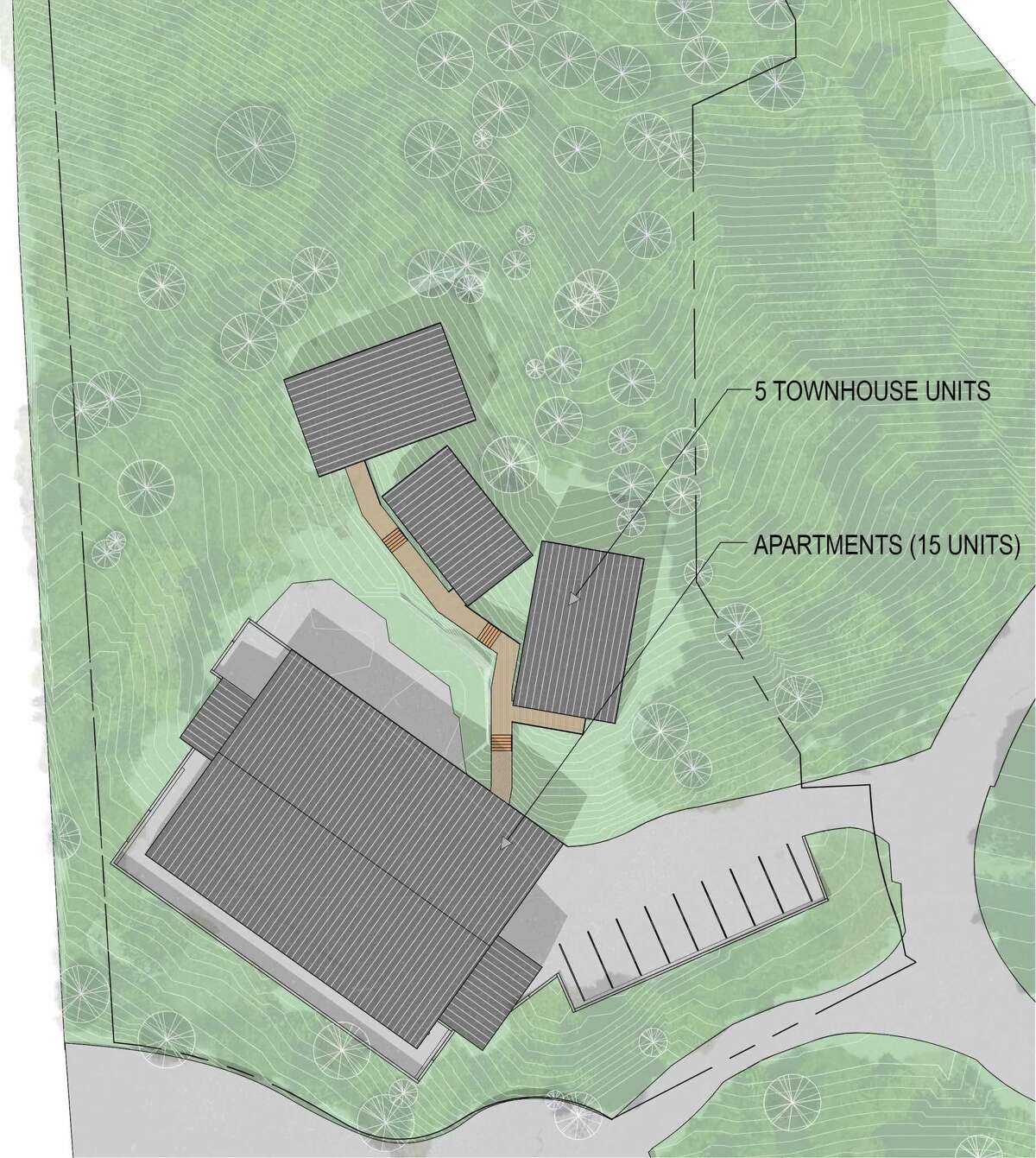

A rendering of the proposed housing development on the property of Sasha Zbrozek. The Los Altos Hills homeowner has filed the project under the builder’s remedy loophole.

OpenScope StudioFor Zbrozek, the opportunity to take advantage of the builders remedy is motivated by a deep belief that the Bay Area, particularly wealthy bedroom communities, have created a dysfunctional region by failing to build enough housing to accommodate its workforce. Zbrozek owns a 1.8 acre property on a steep lot with views across the bay to Fremont and Hayward.

Currently, the property has a house and a pool on it, but Zbrozek has submitted two alternatives for redevelopment. One would add five townhomes and retain his current house and swimming pool. The other would require razing his house and pool and putting a 15-unit apartment building along with the five townhomes. If the larger project is approved, he will sell to an experienced builder and move.

So far, there are dozens of property owners looking at invoking the builder’s remedy, but only a few have pulled the trigger, according to Sonja Trauss, executive director of YIMBY Law, which has sued several cities for not having compliant housing elements.

Trauss said she knows of property owners in Burlingame, Fairfax, Oakland, Sausalito and Palo Alto who are likely to file applications, but that many are hesitant given that the builder’s remedy has only been in effect for two weeks.

A rendering of the proposed housing development on the property of Sasha Zbrozek. The Los Altos Hills homeowner wants to replace his house and pool with townhomes and apartments.

OpenScope StudioShe said the lack of applications so far, “is about what we expected. I’m glad anybody is trying it since there is so much uncertainty.”

UC Davis Professor Chris Elmendorf, an expert on California housing law, said that developers may be waiting to see what cities come into compliance with housing element law in the coming weeks. Several developers are poised to file projects in Berkeley and Oakland, but may be hesitant because of the speculation that both of those East Bay cities may be close to getting state certification, he said.

“I think it’s wait and see,” said Elmendorf. “In Southern California there were a couple of bigger developers who took a run at it and proposed several developments. I don’t know if there are any major developers in the Bay