A few months ago I published a post called Overcoming male reproductive greed. I was then urged from the comments section to think it through more carefully and develop the idea further. So that’s what I did. I have now written it out more explicitly divided between two new posts. This first post is about why male reproductive greed mostly prevents human societies from developing. The second one is about why human societies started developing after all.

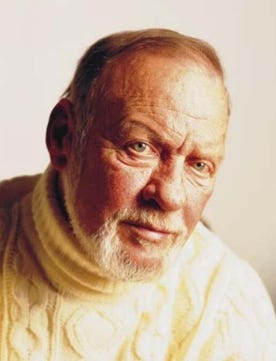

If there were a prize for Most Maltreated Scientist of the 20th Century it should probably go to Napoleon Chagnon. Chagnon was an anthropologist who dedicated his whole career to the study of the Yanomamö of the Amazon rainforest. Chagnon first met the Yanomamö in 1964, only a few years after their first contact with civilization. The Yanomamö were some tens of thousands of people in the rainforests between Venezuela and Brazil. They cultivated plantains and hunted for a living. They lived in villages of between 100 and 400 people. Their villages often split into smaller villages when disagreements arose. Inter-village warfare was rife.

Napoleon Chagnon kept visiting the Yanomamö for over 30 years. He learned the language and got the nickname Pesky Bee because he always pestered people with his questions. He mostly did what anthropologists do: He observed daily life and studied kinship patterns. Inspired by the sociobiological thoughts of some of his colleagues, most notably O. E Wilson, he made calculations from his data in order to estimate evolutionary pressures.

In spite of his rather ordinary anthropological fieldwork, Chagnon managed to stir more controversies than most. In part that was because he became more famous than most anthropologists. Chagnon had a favorable combination of gifts: He was both a good field worker and a good writer. His books became well-known even outside of academic circles.

The controversies culminated in the year 2000, when journalist Patrick Thierny published Darkness in Eldorado, a book where he accused Napoleon Chagnon of several very serious crimes: of deliberately spreading measles to the Yanomamö, of arming them so they could kill each other more efficiently and, of course, of being wrong about everything. The book made Chagnon a canceled person in anthropological circles. Not because the accusations were proven true, but because it gave him a bad reputation that could spill over to the field as a whole. This was a sad prequel to contemporary cancel culture: Never mind who is guilty. Reputation is everything.

Patrick Thierny’s worst accusations were one by one proven fraudulent. After ten bad years, Napoleon Chagnon’s name was more or less cleared. The question whether Napoleon Chagnon was guilty of criminal behavior has been answered and the answer is a firm no. The question that remains is: Why did the accusations stick so well? What made Napoleon Chagnon such a plausible villain?

In 2000, Napoleon Chagnon had been controversial in anthropological circles for several decades. The origin of the controversies were the reports from Chagnon that the Yanomamö waged war, a lot of war. According to Chagnon’s calculations about 30 percent of Yanomamö men and 10 percent of women died from human violence. Chagnon asked the Yanoma