What are Lichtenberg figures, and how do we make them?(Last updated 05/05/22)

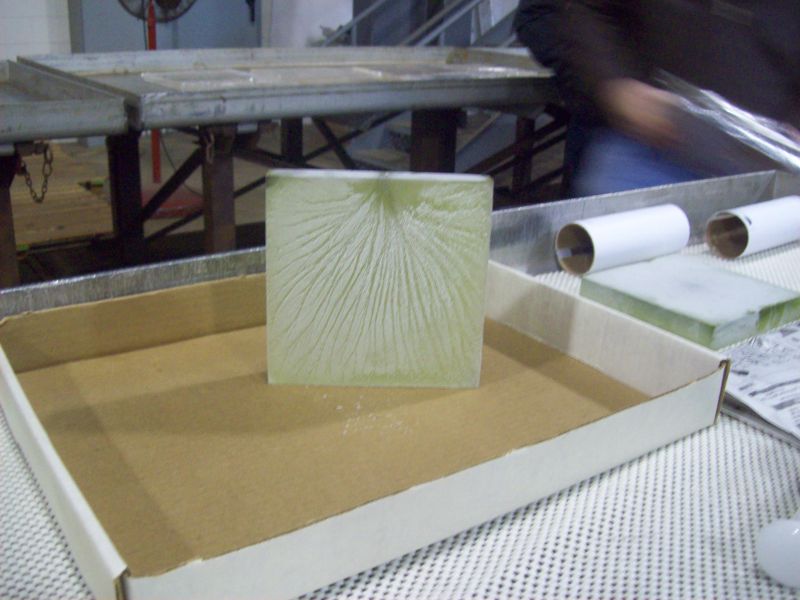

Doubly-Irradiated “Windblown Lightning” Sculpture

This Captured Lightning® sculpture was created by injecting trillions of

electrons into a block of

clear acrylic using a 5 million

volt particle accelerator. Electrons were injected into one side, the

specimen was rotated 180 degrees, and additional electrons

were injected through the opposite side. This created two

intensely-charged layers of excess electrons inside the specimen, each

located about

one-half inch below the

surface. The charge layer on the right side was then manually

discharged. The escaping electrons created a brilliant flash of

miniature “lightning” that propagated upward through the nearest

charge

layer. Additional discharges then grew from the right layer

towards the left layer, forming a complex, beautifully

interconnected 3D structure. The entire discharge took place in less

than 100 billionths of a second! The resulting sculpture above is

illuminated

from below

by blue light emitting diodes (LED’s). Each of our Captured Lightning

sculptures contains an incredibly detailed fractal-like discharge

pattern.

Unlike laser art, every one of our sculptures is a one-of-a-kind

treasure. As they

branch, the discharge channels become increasingly thinner. The

microscopic hair-like tips ultimately disappear into the acrylic. The

smallest

discharges are now thought

to extend down to the molecular level. See our Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) or our one-page explanation for a quick overview of how these beautiful objects are created, or you can get all the details from this web page.

(Sculpture size: 3 x 3 x 2 inches or 7.6 x 7.6 x 5 cm)

What are Lichtenberg figures? A bit of history…

“Lichtenberg figures” are branching, tree-like patterns that

are created by the passage of high voltage electrical discharges along the surface, or inside,

electrically insulating materials (dielectrics).

The first Lichtenberg figures were actually 2-dimensional “dust figures”

that formed when airborne dust settled on the surface of electrically-charged

plates of resin in the laboratory of their discoverer, German

physicist Georg Christoph Lichtenberg

(1742-1799). Professor Lichtenberg first observed this in 1777,

demonstrated the phenomenon to his physics students and peers, and reported his findings in his memoir (in Latin): De Nova Methodo Naturam Ac Motum Fluidi Electrici Investigandi (Göttinger

Novi Commentarii, Göttingen, 1777). The English translation of the title is, “Concerning the New Method Of Investigating the

Nature and Movement of Electric Fluid”. Lichtenberg’s translated paper is contained in Appendix A of a Masters thesis by Mark A Payrebrune (“Experimental Morphology of Lichtenberg Figures”, McGill University, Montreal, Canada, 1979). The translated document (by Dr. J. Blain, Classics Department at McGill University) contains the following passage that describes Lichtenberg’s initial discovery:“At the beginning of spring 1777, after the completion of the new

Electrophore, everything in my little room was still covered with

extremely fine resinous dust that had settled, between the scraping and

the shaving of the instrument’s base or stand, on the walls and books.

As soon as a draft in the air arose, the dust fell, much to my

annoyance, on the conducting disc of the Electrophore. Often afterwards,

when I held the disc suspended from the ceiling of my room, it turned

out that the dust, as it settled on the base, did not cover it

completely, as it previously had covered the disc, but only in certain

areas. Much to my great joy, it gathered to form little stars, dim and

pale at first, but as the dust was more abundantly and energetically

scattered, there were very beautiful and definite figures, not unlike an

engraved design. Sometimes there appeared almost innumerable stars,

milky ways, and great suns. There were arcs, unclear on their concave

side, but radiant on their convex side. Very glittering little twigs

were formed, similar to those which frozen moisture produces on glass

window panes. There were clouds of different shape and shadows that were

visible in varying degrees … But the most pleasing sight

presented itself to me, when I saw that these figures could not be

easily erased, as I tried to wipe away the dust with a feather or a

rabbit foot. I could not prevent these same figures, which I had just

erased, from shining forth once more, and somehow, more brightly.

Therefore l placed a piece of black paper smeared with a viscous

material on the figures and pressed down lightly. I was able to produce

imprints of the figures, six of which the Royal Society has seen. [Note:

see figures below]. This new kind of Typography has been

extremely satisfying to me, hastening as I was to more remote

preoccupations and having neither the time nor the inclination of

sketching the figures or destroying them all.”During his subsequent studies, Professor

Lichtenberg used various high-voltage electrostatic devices to electrically charge

the surfaces of various insulating materials including resin, glass, and

ebonite (hard

rubber). He then sprinkled mixtures of finely-powdered

sulfur (yellow) and minium

(“red lead”, now called lead tetroxide) onto the

charged surfaces. He

found that powdered sulfur (which becomes negatively-charged by rubbing against its container) was more strongly attracted to

the

positively-charged regions on the surface. Similarly, frictionally-charged particles of

red lead acquired a positive charge and were attracted to

negatively-charged regions. The colored powders

made previously-hidden regions of stranded surface charges, as well as their

polarity, clearly visible. We now know that these charged surface regions

were previously deposited by small sparks of static electricity. The

sparks deposited isolated patches of electrical charge onto the surface

as they

flashed along the surface of the insulator. Once

deposited onto the insulator surface, the charges remain

stranded for a very long time since the insulator prevents them from moving and dissipating. Lichtenberg also discovered

that the appearance of

positive and negative dust figures was markedly different.

Discharges created by a positively-charged high-voltage

terminal were star-like, with long, branching paths while discharges from negatively-charged terminals were shorter,

rounded, and

fan-shaped or shell-shaped. By carefully pressing a piece of paper onto the

dusted

surface, Lichtenberg found that he could transfer the images onto a piece of paper,

demonstrating what eventually became the modern processes of xerography and laser printing. The underlying physics that created Lichtenberg’s dust figures evolved to become the

modern-day science of plasma physics.The

following demonstration video is a replication of Lichtenberg’s experiments

using a mixture of powdered lead tetroxide and sulfur to highlight positive

(yellow) and negative (red) Lichtenberg figures. In the video a Wimshurst electrostatic generator is used as the high voltage source instead of an electrophorus,

as originally used by Lichtenberg, but the principles are otherwise the

same. In the video, branching positive Lichtenberg figures are created first,

followed by shell-shaped negative Lichtenberg figures.

Many other physicists, experimenters, and artists studied Lichtenberg

figures over the next two hundred years. Notable 19th and 20th century

researchers included physicists Gaston Planté and Peter T. Riess (mid-1800’s). In the late 1800’s, French artist and scientist Etienne Leopold Trouvelot created “Trouvelot figures” – now known to be photographic Lichtenberg figures – using a Ruhmkorff coil as a high voltage source. Other researchers included Thomas Burton Kinraide (1890’s), and professors Carl Edward Magnusson, Maximilien Toepler, P. O. Pedersen, and Arthur Von Hippel

(1920’s-30’s). Most modern researchers and artists used photographic film to

directly capture the faint light emitted by the electrical

discharges. A wealthy English industrialist and

high voltage researcher, Lord William G. Armstrong,

published two beautiful full-color books showing some of his high

voltage and Lichtenberg figure research. Although these books are now

quite scarce, a copy of Armstrong’s

first book, “Electric Movement in Air and Water, with Theoretical

Inferences”, was made available through the kind efforts of

Jeff Behary at the Turn of the Century Electrotherapy Museum.

In the mid-1920’s, Von Hippel discovered that Lichtenberg figures were

actually created through complex interactions between corona discharges

or small electrical sparks, called streamers,

and the dielectric surface below. The electrical discharges deposited

matching patterns of electrical charge onto the dielectric surface

below where they became temporarily stranded. Von Hippel also

discovered that increasing the applied voltage, or reducing the

surrounding gas pressure, caused the length and diameter of

the individual paths to increase.

Riess discovered that the diameter of a positive Lichtenberg figure was about 2.8

times that of a negative figure of the same voltage. The relationships between the size of Lichtenberg figures versus voltage

and polarity were utilized in early high-voltage measuring and recording instruments, such as

the klydonograph,

to measure both the peak voltages and polarities of

high voltage impulses. A klydonograph, sometimes called “Lichtenberg’s camera”, could photographically record the size

and shape of Lichtenberg figures that were generated by abnormal

electrical surges on electrical power lines due to lightning

strikes. Klydonograph measurements allowed lightning researchers and power

system designers in the 1930’s and 1940’s to

accurately measure lightning-induced voltages, thus providing critical

information about the electrical characteristics of lightning strikes.

This information allowed power engineers to create

“man-made lightning” with similar characteristics under

laboratory-controlled conditions so that they could test the

effectiveness of

various lightning-protection approaches.

Lightning protection has since evolved to become an essential part of

the design for all

modern

electrical transmission and distribution systems. A schematic

diagram of the active parts of a klydonograph is shown on the leftmost

drawing below,

along with examples of klydonograms from positive and

negative

high voltage transients of various amplitudes versus polarity. Notice

how positive Lichtenberg figures are

considerably longer than negatives figure even though

the peak voltages are of equal magnitude.

A more modern version of this device, called a teinograph, used a

combination of delay lines and multiple klydonograph-like sensors to

capture a series of time-shifted “snapshots” for a given transient,

allowing engineers to capture the overall wave shape of a HV transient

event. Although they were eventually replaced by modern electronic

equipment, teinographs were still used through the 1960’s to study the

behavior of

lightning and switching transients on HV transmission lines.

Lichtenberg figures are now known to occur during the electrical breakdown of gases, insulating liquids, and solid dielectrics.

Lichtenberg figures may be created within billionths of a second (nanoseconds)

when dielectrics are subjected to very high electrical stress, or they may develop over years through a progressive series of small, low-energy, partial discharges.

Countless partial discharges on the surface or the interior of solid

dielectrics often create slowly-growing, partially-conductive 2D surface

Lichtenberg figures or internal 3D “electrical trees”.

2D electrical trees are often found along the surfaces of contaminated

power line

insulators. 3D trees can also form, hidden from view, inside dielectrics

due to the presence of small impurities or voids, or at locations

where an insulator has been physically damaged. Since these

partially-conductive trees can eventually cause the

complete electrical failure of the insulator, preventing

their initial formation and growth is critical to the long-term reliability of

all high-voltage equipment.

The study of electrical trees and their prevention has been critical to

the reliable design of the high-voltage power transmission systems that

transfer electrical power to our homes and businesses.3D Lichtenberg figures inside transparent plastic were

first created by physicists Arno Brasch and Fritz Lange in the late 1940’s.

Using

their newly-invented electron accelerator, they injected trillions of

free electrons into plastic specimens, triggering electrical breakdown and creatingcarbonized internal Lichtenberg figures. Electrons are tiny, negatively charged particles that orbit the positively-charged

nucleus of the atoms that make up all condensed matter. Brasch and Lange used high voltage pulses from a

multi-million volt Marx Generator

to drive a pulsed electron beam accelerator.

An article about their research and their accelerator (which they

called a “Capacitron”) originally appeared in the March 10, 1947 issue of LIFE

Magazine. The Capacitron could deliver a three-million volt pulse, and

could generate a powerful blast of free electrons with an incredible peak current of

up to 100,000 amperes. The glowing region of heavily-ionized air created by the exiting high-current

beam of electrons resembled a bluish-violet rocket engine flame. A complete set of B&W pictures,

including Lichtenberg figures inside a clear block of plastic, has

recently become available online, as has another article with color pictures

from the April, 1951 issue of Popular Mechanics. In 1944, Brasch

founded the Electronized Chemicals Corporation (ECC), a pioneering researcher of using electron beams to

cross-link monomers and polymers to improve their electrical and

physical properties. ECC was eventually purchased by the 3M Company in

1985.

The first formal scientific study of the injection and movement of electrical charges and charge trapping/detrapping within

dielectrics was conducted by Brazilian physicist Dr.

Bernhard Gross in the early 1950’s. Dr. Gross confirmed that internal Lichtenberg figures could be created within a number of different polymers

and glasses by injecting them with high-energy electrons from a particle accelerator. The

techniques that we use to make our modern sculptures are built upon the

theoretical work and experimental techniques originally developed

by Brasch, Lange, and Gross. 3D acrylic Lichtenberg figures are

sometimes called “electron trees” or “beam trees”. We call our

state-of-the-art creations Captured Lightning® sculptures.How do we make our Acrylic Captured Lightning® sculptures?

Since 2004, we have developed and refined irradiation and fabrication

techniques to create a wide variety of beautiful 2D and 3D sculptures.

We begin by carefully cutting and polishing various shapes from a clear, glass-like polymer called polymethyl methacrylate (or PMMA).

This material, commonly called acrylic, is sold under various

trade

names such as Lucite, Plexiglas, or Perspex (UK). Acrylic has a unique

combination of

high optical clarity and superior electrical

and mechanical properties. Besides being an excellent electrical

insulator,

acrylic is actually clearer than glass! We have tried a number of other

clear polymers, such as polycarbonate

(PC), polystyrene (PS) , polyester/polyethylene terephthalate (PET), epoxy, and clear polyvinyl

chloride (PVC). Lichtenberg figures can be made inside all of these

polymers with varying

degrees of success. However, the branches tend to be dark gray or even black instead

of the sparkling white, mirror-like figures seen within acrylic. We

have also experimented with making Lichtenberg figures in glass. However, since glass Lichtenberg figures often explosively shatter upon discharge or, unpredictably, days or even months later, we no longer make them.We inject electrons into acrylic specimens using a 5 million volt, 150 kW commercial particle accelerator called a Dynamitron.

The heart of this device is the accelerator tube – a huge three-story

high “vacuum tube” that operates at voltages between one and

five million volts. At the top of the tube, electrons are emitted by a

small, white-hot tungsten filament. The filament is connected to

the negative terminal of an adjustable multi-million volt power supply. The bottom of the tube is

connected to ground and the positive terminal of the high voltage supply. This configuration creates a very strong

electrical

field that accelerates electrons emitted from the filament. As they

“fall” though the large potential difference, and they acquire a very

high velocity. The

bottom of the vacuum tube has very thin (only 2.3 thousandths of an

inch thick!) titanium

window that separates the high vacuum on the inside

from atmospheric air on the outside. The high-velocity electrons pass

right through

the titanium window, almost as though it wasn’t there! Trillions of free

electrons emerge

through the outside surface of the window, travel

24 inches through air then crash into our acrylic specimens on the

moving carts below. Although the average lifetime of free electrons in

air is only 11 billionths of a second, that’s more than enough

time for them to work their magic on our acrylic specimens.

The energy of the accelerated electrons is measured in millions of electron volts (or MeV).

Most of our sculptures were created using electrons that had energies

between 2 and 5 MeV. At these energies, electrons are traveling at relativistic velocities – between 98.5% and 99.6% of the speed of light. During irradiation,

these energetic electrons burrow deep inside the

acrylic before finally coming to rest. The penetration depth is a

function of

the energy of the electrons in the beam, the target material’s

dielectric properties, and its atomic density. The charging process

is called “deep dielectric charging”. The higher the energy of

the electrons in the beam, the deeper they penetrate. For example,

electrons with an energy of five MeV will

penetrate about one-half inch into acrylic, but a 1/16-inch thick piece of much denser lead will completely block them.

When

a thick piece of acrylic is irradiated, huge numbers of electrons

accumulate

inside the specimen, creating a strongly-charged cloud-like layer called

a space

charge. Because acrylic is an excellent electrical insulator, injected

electrons become temporarily trapped inside the acrylic. By passing

thick specimens

through the electron beam in two or more passes, changing specimen

orientation between passes, or rotating them while they’re

being irradiated, complex 3-dimensional space charge regions can be

created inside the acrylic. As electrons accumulate during irradiation, the

electrical stress (called the electric field or “E-field”) inside

the acrylic dramatically increases, reaching several million volts

per

centimeter. We normally charge our specimens to just below the point

where they’ll break down. We then force the charged specimens to release

(“discharge”) the electrons at the desired location by poking them with a

heavily-insulated, pointed

metal tool. This creates a small fracture that greatly concentrates the E-field at that point. The intense electrical field at the tip of the fracture overcomes the dielectric strength of the acrylic, initiating complete electrical breakdown of the specimen. During breakdown, some of the chemical

bonds that held acrylic molecules together suddenly break, stripping away free electrons in a process

called ionization.

The newly-freed electrons become accelerated by the

extreme electric field, and as they collide with other

molecules, they rapidly create an ever-increasing number of new electrons in an exponentially-growing runaway process called avalanche breakdown.Within

billionths of a second, a tree-like network of white-hot plasma channels form within

the acrylic and, with a bright flash and a loud BANG, the

material undergoes complete dielectric breakdown.

The previously-trapped electrical charges rush out in a river-like

torrent. Thousands of smaller tributaries dump their

share of stored charge into larger channels that eventually merge into a

single, brilliant discharge path that exits the acrylic. Although images

and videos appear to suggest that we’re injecting high voltage into each piece, we are

actually removing the excess

charges that were previously trapped inside each piece. Dielectric breakdown occurs with incredible speed – the main electrical discharge

within a 4-inch square specimen lasts less than 120

billionths of a second (120 nanoseconds)! Some physicists think that dielectric

breakdown within a charge-injected solid may be the most energetic

(explosive) known chemical reaction.

The

following image shows a 12 x 12 x 1 inch

specimen being discharged. In the image, camera settings were adjusted

to reduce the brilliance of the discharge so that the individual plasma

channels can be

seen. Note the bright descending discharge that exits from the discharge

point, across the top surface of the specimen, and then to the groundedmetal table below:

(Photo courtesy of Terry Blake)

As the miniature lightning bolts blast their way through the acrylic,

they

create millions of microscopic tubes and fractures, leaving behind a

permanent “lightning fossil” deep inside the acrylic. The peak current

within the electrical discharge reaches hundreds, or even thousands of

amperes, depending upon the physical size of the specimen. The white-hot high-density plasma within the

confined discharge channels causes the nearby acrylic to vaporize

and fracture, and highest-current “roots” often char the surrounding acrylic. The

exit point of the discharge creates a small crater on the surface as hot gases explosively exit the specimen.

Surprisingly, although we inject a huge amount of negative charge into

our specimens, the electrical discharges originate from spark tips which aremore electrically positive (versus the space charge layer), so all of

our Captured Lightning® sculptures are actually “positive” Lichtenberg

figures! Single-discharge branched figures continue to split as paths

become finer, filling the charged area, but they never cross or form

loops. The finest tips eventually disappear into the acrylic.Some specimens self-discharge while they’re being irradiated by the

electron beam. This

is usually caused by a small surface scratch or imperfection, left-over

manufacturing or fabrication stresses, or an internal defect, such as a

small bubble or inclusion, inside the acrylic. A

self-discharged

specimen will continue to discharge numerous times while it is being

irradiated as the electron beam continues to inject new charge into the

specimen. Unlike the neatly-branched structures seen in

manually-triggered sculptures, self-triggered sculptures typically

develop a

thicker, mat-like tangle of chaotic discharges, or a complex combination

of

dendritic and chaotic patterns. Because of their complexity,

self-discharged specimens are often among some of our most fascinating

sculptures.

Video clip of a huge 15 x 20 x 2 inch sculpture being discharged:

Following

is a short video clip showing a huge 15″ x 20″ x 2″ specimen being

discharged. The specimen was first

charged on one side using a 5 MeV electron beam. The electrically-charged

specimen was then (very carefully!) flipped over and irradiated once

more on the other side. This created two independent charge layers,

each located about 1/2″ below the large surfaces. Prior to discharging,

the estimated potential of these internal layers was over 2.5

million volts. Because there were two very large charge layers, this

specimen stored significantly more electrostatic energy than most of our

other specimens – more than four kilojoules! Safety precautions were

necessary to prevent the possibility of receiving a painful, and potentially dangerous, electrical

shock.Although the main discharge is quite brief (under 500 billionths

of a second for this specimen), the video successfully captured the brilliance of the 4

kilojoule electrical discharge in a single video frame (shown below). Numerous

secondary discharges continued to intermittently flash after the main discharge. These

continued with decreasing frequency for over 30 minutes. This video is courtesy of

Dr. William Hathaway, GCL Laboratories. The resulting sculpture, cradled within

a custom walnut light base and illuminated by an array of white and

blue LED’s, is also shown below.

(Click on above image for high-resolution image)

The resulting Lichtenberg Figure is a series of branching hollow tubes surrounded by conchoidal

(shell-shaped) fractures. Conchoidal fractures are characteristic of the way that glassy (amorphous)

materials fracture when stressed beyond their breaking point. Since the

countless

fractures behave as tiny mirrors, illuminating a figure through the

edges causes the entire Lichtenberg figure to glow brilliantly

with the reflected colors of the external light source.

Lichtenberg figures have fractal properties

The

branching pattern of a Lichtenberg figure looks similar at various scales of

magnification. This property is called “self-similarity”, and it suggests that Lichtenberg

figures can be mathematically described through a branch of mathematics called Fractal Geometry.

Unlike most common geometric forms, fractal-like objects do not have

even-integer dimensions. Instead, they

have dimensions that lie between 1 and 2 (for 2-dimensional fractals) or between 2

and 3 (for 3-dimensional fractals). Lichtenberg figures

may be one of the first fractal-like forms created by man. Our

branching 2D Lichtenberg figures have a

fractal dimension that varies between 1.5 (for thin, sparsely branching discharges) to 1.9 for

dense, fern-like bushy discharges. Most of our standard 2D sculptures have a

fractal dimension of about 1.7. Our 3D sculptures typically have a fractal dimension of about 2.5.

The appearance of

the resulting Lichtenberg figures depends upon how much charge was injected into the

acrylic and where and when the specimens are discharged. The technical terms for branching figures are

dendritic or ramified (tree-like).

If a larger amount of electrical charge is injected

into a specimen, very dense dendritic discharges can be created such as

in Figure 1 below. These very dense discharges are similar in appearance

to fern fronds (“filiciform”) or plume agates.

Specimens exhibiting this

form were heavily charged to just below the point of self-breakdown and

then immediately discharged. If we reduce the amount of injected charge,

more classical, lightning-like or tree-like discharges are created

(Figure 2). If premature breakdown occurs while we’re actively

irradiating

a specimen, the resulting discharges form a thicker, densely tangled

mat of “chaotic”

discharges

(Figure 3). The fractal dimension of chaotic discharges is currently

unknown. In chaotic discharge specimens, after the initial breakdown,

newly-injected electrons from

the accelerator recharge smaller nearby regions, causing them to

repetitively discharge in random directions into existing discharge channels. The rapidly changing

internal electrical fields create a much thicker mat of densely chaotic

discharges that

are reminiscent of interconnected nerve cells and neural networks.

Some of the most complex and fascinating patterns

occur when a specimen self-discharges about halfway through the charging

process, creating dramatic discharges that change from being densely dendritic

to densely chaotic across the sculpture.

The

self-similarity of dendritic discharges can easily be seen in the

following sequence of zooms from a 12″ x 12″ Lichtenberg Figure.

Although the branches become finer and hairlike, the overall branching

structure remains similar until the finest tips ultimately disappear at

the very edges of the discharge structure. Some recent research suggests that this dendritic pattern may extend to the molecular level.

Similar fractal-like patterns are prevalent in nature. They are seen in

aerial views of rivers and their tributaries, and organic structures

such as branching tree limbs, your body’s circulatory system, and within

various organs such as lungs, kidneys, and the liver. The satellite

view in the left image below shows a river

drainage system near Grand Junction, Colorado, USA. The rightmost image is a

casting of the bronchial tree of a human lung (courtesy Paul Cazeaux,

PhD student at Laboratoire Jacques-Louis Lions (LJLL), Paris, France).

The similar branching structure of all of these systems may be a

consequence of a recently proposed new law of physics, the Constructal Law,

which states that Nature tends to develop a hierarchical branching

network of paths that result in most efficient flow. The flowing

material can be water, air… or even electrons!

Lichtenberg figures can be mathematically modeled using an iterative growth process called “Diffusion Limited Aggregation” (DLA). A more accurate model, that combines an electric field with DLA, is called the Dielectric Breakdown Model (DBM).

The DBM appears to accurately describe the forms of Lichtenberg

figures that occur under various electrical field intensities on the

surface or within solid, liquid, and gaseous insulators.

Other interesting properties: fluorescence, solarization, birefringence, and the discharge-free zone

When

acrylic is bombarded by high-energy electrons, it glows brilliantly

with a blue-white color. Radiation chemistry studies suggest that this

is mainly due to luminescence that peaks at a wavelength of about 435 nm. However, acrylic also generates fainter glows from X-ray fluorescence, and Cherenkov radiation

as high velocity electrons interact with acrylic molecules. The

detailed light-producing mechanisms for electron-irradiated acrylic are

not fully understood.

Newly-irradiated specimens develop a discolored layer in the region

between the irradiated surface(s) and the

discharge layer. This phenomenon, called solarization, appears to be caused by various interactions between the injected electrons and the molecular structure of the acrylic. During

irradiation, electrons in the beam are initially traveling at over 99%

of the speed of light. As they penetrate the specimen, they collide with

acrylic molecules, rapidly coming to a stop within a fraction of an

inch. Electrons in the beam have considerable kinetic energy,

and as they collide with

the atoms in the acrylic they release this energy

as heat and x-rays.

In acrylic, most solarization seems to occur in the regions directly

hit by the electrons. However, regions that are intentionally covered by sheet lead (to prevent

electrons from hitting some areas of the acrylic) may also exhibit

solarization within deeper regions of the acrylic. As electrons crash into

the lead mask, they radiate intense x-rays that apparently create a darker region of

solarization in the acrylic immediately underneath the mask.

Energetic collisions with electrons, x-rays, and the build-up of excess electrons stimulate chemical and

physical reactions that alter the physical and optical properties of the

acrylic. Deeply-trapped electrons may remain stranded within the

acrylic for several years. These create color centers

which also contribute to solarization. While some of these changes may last

for only minutes, others persist for months or years after

irradiation, and some appear to be permanent. Although all of the specific causes

of solarization are not completely understood, there is evidence that

irradiation creates longer-lived unstable (“metastable“)

compounds that preferentially absorb light at the blue end of the

spectrum (wavelengths between 250 and 400 nm). Since a portion of the

blue spectrum of ambient light

is absorbed by the solarized region, freshly-irradiated specimens

typically appear green, amber, or sometimes even rose-colored when

illuminated by white light.

The solarization layer in charged acrylic specimens is most often lime-green immediately

after irradiation. Within minutes of being discharged, the solarized layer changes to

brownish-amber, then fades to a lighter amber color over weeks or months. The

amber region usually fades away over months to several

years. The fading process can

usually be accelerated by heating

the

block in the presence of air or by leaving the specimen

in bright sunlight for an extended period of time. As oxygen diffuses

into the

acrylic from the outside surfaces and the porous discharge layer,

it

slowly bleaches the solarized region, causing the solarized layer in between to

gradually become thinner until it eventually disappears entirely.

Most Lichtenberg figures older than 2-3 years are completely bleached. Although older

specimens may no longer show any solarization, many exhibit various

degrees of “fogging” from electron collisions and X-radiation damage to the acrylic’s molecular structure.

Some PMMA specimens exhibit

comparatively little initial solarization, while a small percentage of other

specimens permanently retain their amber color. Permanently-colored specimens

appear to be solarized via a different, deeper penetrating mechanism,

such as X-radiation, since these specimens also tend to be uniformly

solarized throughout their entire thickness. These differences may be due to

subtle variations in the acrylic blends and the specific catalytic agents used by acrylic manufacturers to polymerize the acrylic.The solarized layer is often fluorescent.

An amateur scientist from Australia, Daniel Rutter, discovered that monochromatic light from a green laser pointer apparently changes color

when passed through the solarized layer of a Lichtenberg figure. More

recently, we have discovered that the light from a near-ultraviolet

source, such as a 405 nm Blu-ray laser or blue LED’s, also causes the

solarized region to fluoresce with a yellow-green color. Both effects

appear to be due to the presence of semi-stable fluorescent components within the

solarized layer. And, as the solarization fades over time, so does the

fluorescence.

Most specimens also exhibit slight changes in the

refractive index

in the regions near the discharge layer. This may be due to

residual mechanical stresses near the discharge

fractures or residual electrical charges. Residual

stresses near the Lichtenberg figures can sometimes be seen as

multicolored regions near the discharge plane when a sculpture is

illuminated by polarized

light and then viewed through a second polarizing filter, a

configuration called crossed polarizers. When physically stressed

mechanically or by a large electrical field,

acrylic exhibits a property called birefringence.

When viewed through crossed polarizers, stress- or

electrical-field-induced birefringence

causes changes in color that are directly related to the amount and

distribution of otherwise hidden mechanical and electrical stresses. The

sample below clearly show internal compressive forces created by the

high

internal electrical field. These forces are then mostly relieved when

the

specimen is

discharged. Following are images of the same specimen prior to charging,

fully charged, and then after discharging. Little internal stress is

seen in the initially uncharged specimen. The specimen was then charged

by injecting electrons from the left side. The injected charge forms an

intensely negative layer of charge near the center of the specimen. At

the same time, positive ions (created in the air by collisions between

air molecules and the high-energy electrons in the beam) are strongly

attracted by the internal negative charges. The positive ions attach

themselves to the external

surfaces of the specimen. The outer positive “mirror” charge layer

partially

neutralizes the electrical field created by the internal negative charge

layer, dramatically reducing the electrical field seen outside

the specimen. Attraction between the internal negative

layer and the positively-charged outer surfaces create intense

compressive stresses within the acrylic. For the specimens below, the

compressive force created between the charge layers is approximately 400

pounds per square inch (PSI).

The compression can easily be seen as

colored regions on either side of the center in the middle image. After

the specimen is discharged, both the electrical and mechanical stresses

are greatly relieved

as can be seen in the rightmost image. There are still residual

mechanical stresses near the discharge zone due to all the microscopic

fracturing, and residual electrical stresses left over from embedded

charges that were not removed by the main spark discharge. Click on

any of the individual images below to see full-sized images. Further

study, using a monochromatic light source, is planned for the future.

Finally, all of our sculptures have a

discharge-free

zone along the outside boundary. Since acrylic is not a

perfect

insulator, some of the injected charge “leaks away” through the

perimeter that separates the internal negative space charge layer and

the positively-charged outer surfaces. The charge leaks away most

quickly in those areas where the

electrical field is greatest, such as along the perimeter. The boundary

is also influenced by positive charges on surface of the specimen. As

propagating

streamers approach the edges of the sculpture, the electrical field

“seen” by the tips of the

growing discharges is dramatically reduced as they approach the positive

surface charges. As the advancing streamer tips approach the outer

edges, most streamers thin and die out. However, some discharge tips

suddenly make an abrupt turn and then continue to grow parallel to the

nearby edge. We suspect that the positive charges on the

large outer surfaces force the discharges to be confined to a thin

layer, parallel to the

outer surfaces of the specimen. “Iced ‘bergs” and negative Lichtenberg figures. And, do we get curved figures in a magnetic field?

From studies done by other researchers, we knew that acrylic specimens

could retain their injected

charge for weeks, or even months, if

chilled, irradiated, and subsequently maintained at dry ice

(-109F/-78.5C) temperatures. One of our team members, Todd

Johnson, has christened these frozen objects as “Iced ‘bergs”. At room temperature,

injected charge leaks away over a few minutes to a few

hours for commercial acrylic. Chilling acrylic

significantly reduces the speed that free charges can move inside the

acrylic, and this dramatically increases the time that trapped charges

can be stored. At dry ice temperatures, trapped charges can apparently

be stored indefinitely. We have confirmed virtually full charge

retention over

several weeks, and

other researchers have demonstrated charge storage for up to six months.

When later discharged, these specimens behave in a fashion similar to

freshly-charged specimens. The initial lime-green color of the solarized layer is also retained in

chilled specimens until they are discharged. This suggests that the green color

is

related to the high density of electrons that remain

trapped before discharging. Or perhaps this proves that electrons are green? Anyway, once discharged, chilled specimens rapidly

lose their green color, changing to an amber color.

Chilled specimens develop a heavy layer of frost when

exposed to humid air. When we discharge a specimen, we produce a

“positive”

Lichtenberg figure inside the acrylic. Photographic evidence confirms

that the exiting sparks then “wrap around” the specimen. The surface

sparks cover the exterior surfaces of the

specimen, discharging the external layer of positive charges that have

attached themselves to the

specimen’s surfaces. As the external surface discharges branch out, they

produce a

“negative” Lichtenberg figure along the large surfaces of the specimen.

However, the negative surface discharges are considerably fainter than

the

brilliant internal discharges, so they’re quite

difficult to see or photograph. We accidentally discovered that, when a

charged specimen is coated with frost, the negative discharges along the

acrylic

surface blast away the frost layer immediately above the discharges.

This makes the main paths taken by the negative discharges clearly

visible. The following “iced ‘berg” was discharged by Todd

Johnson and Dr. Timothy Koeth during our 2010 production run.

As

can be seen, the resulting negative Lichtenberg

figures that blasted through the frost layer show considerably less branching

than positive

internal figures… just as professor Lichtenberg observed

over 200 years ago. Other experimental evidence suggests that the “branching

angle” (at the fork where a discharge path splits) for negative

discharges is centered around 29 degrees, while the branching angle of

positive discharges appears to be centered around 39 degrees.

We also wondered if an externally-applied magnetic

field might cause discharge paths inside the acrylic to become curved.

It was known that Lichtenberg figures created within gases along

dielectric surfaces become curved due to Lorentz force acting on the

moving charged particles within the electrical discharges. The stronger

the magnetic field, the greater the curvature:

&