The Value of Foreign Diplomas by MrBuddyCasino

This was a timed post. The way these work is that if it takes me more than one hour to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. You can find my previous timed post here.

You have two practically identical résumés sitting in front of you: same level of education, same limited experience because they’re young, same claimed technical expertise, and so on. But, there’s one key difference: Applicant A went to Harvard, and Applicant B earned their degree from DeVry University. You want to hire the best employee, so which one are you more likely to call back?

The honest answer from almost everyone will be Applicant A, and there’s good reason to make that choice: People who go to Harvard are, all else equal, likely to be more capable than people who go to lesser-ranked universities. The screening process to get into Harvard is more intense than elsewhere, so the wise employer picks up the phone and knows exactly what to do in this situation.

But somehow people seem to forget this when it comes to other comparisons. One such comparison is between America’s natives and its immigrants. Let’s look at that.

The OECD cognitively tests the adults of various nations as part of the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies or PIAAC. In the latest PIAAC iteration, participants’ literacy, numeracy, and adaptive problem solving skills were tested. The literacy questions were like this:

The questions were entirely not hard, but they’re hard enough that they manage to discriminate different ability levels reasonably well. The numeracy questions were similarly easy. For example, here’s the “Render Mix” question:

The adaptive problem solving section has less obvious content. Defined as “the capacity to achieve one’s goals in a dynamic situation, in which a method for solution is not immediately available”, adaptive problem solving is said to require participants to engage “metacognitive processes” to define and address different problems. As an example, here is the “Best Route” question:

Again, not hard. But if you sum up people’s correct (1) and wrong (0) answers, you get a nice bell curve of scores without much range restriction in most participant countries. For my purposes, I’ll be using the data from just one country though: the United States of America.

In the U.S., the tests are administered entirely in English, and in the latest wave, they’re administered in a computerized format. Given the language of the test and the nature of the comparison we’re about to embark on, an obvious question is Are the tests biased by language? Immigrants might not have enough English language experience to fully perform on the tests for reasons of experience alone. But this is no big deal for a few reasons. Substantively, English language skills matter, so deficiencies in English signal assimilation issues. Also, we can compare immigrants who’ve been in the U.S. longer to those who are more recent arrivals. But more directly, we can just see if the tests display measurement invariance. If they do, there’s no language issue and scores are directly comparable.

Since we have item-level data I used the method in this paper to compute a measure of aggregate bias (ETSSD) for items at the subscale level with at least 80% pre-imputation coverage in three groups: Natives with degrees, immigrants with degrees from the U.S., and immigrants with degrees from outside the U.S. I did the bias comparison between natives and immigrants as a whole because the sample size for immigrants was only a couple hundred. The result of this analysis isn’t very meaningful: Literacy was biased 0.01 d in favor of natives, numeracy was biased 0.05 d in favor of immigrants, and adaptive problem solving was biased 0.06 d in favor of natives. This might be meaningful in some other context, but the scale of the native-immigrant gaps in performance was much larger, as you’ll see.

In order to make scores meaningful, I’ve put the scores for natives with any degree, immigrants with any degree from the U.S., and immigrants with any degree from outside the U.S. into percentile terms, where the 50th percentile is defined as the median for all natives irrespective of education.

U.S.-educated immigrants do marginally better than natives as a whole, but considerably worse than natives who have any sort of degree. But more shockingly, natives without degrees who only have some college experience also manage to outperform both types of immigrant, with literacy, numeracy, and adaptive problem solving percentile scores of 54, 53, and 59. Native college dropouts only lag on numeracy, and not significantly.

In standardized terms, U.S. natives with degrees respectively outperform immigrants with U.S. and foreign degrees by 0.30 and 0.62 Hedge’s g in literacy, 0.19 and 0.35 g in numeracy, and 0.43 and 0.53 g in adaptive problem solving. Accounting for the bias mentioned above has practically no effect on this picture.

I’m not the first person to notice this. Just a few years ago, Jason Richwine analyzed an earlier wave of PIAAC data and he observed the same pattern. I’m effectively replicating this:

Unfortunately, then and now, the amount of data isn’t enough to really pick apart every little category of immigrant. We can split the data up, but the results beyond the big picture quickly become extremely statistically uncertain. If we want more certain answers about exactly how skilled different immigrant national, occupational, and educational groups are, the easiest way would be for the U.S. to restart the New Immigrant Survey.

We do have a decent amount of power to break apart the native group. We know, for example, that natives with bachelor’s degrees alone score better than immigrants with U.S. degrees of any sort, those with bachelor’s degrees, and even those with advanced degrees. Natives with advanced degrees score even more highly. We also know more heavily-replicated facts, like that White natives score about 1 g above Black natives, and that they score higher at the same levels of education, that male and female natives score similarly highly, and so on. But let’s focus back on immigrants by talking about potential immigrants.

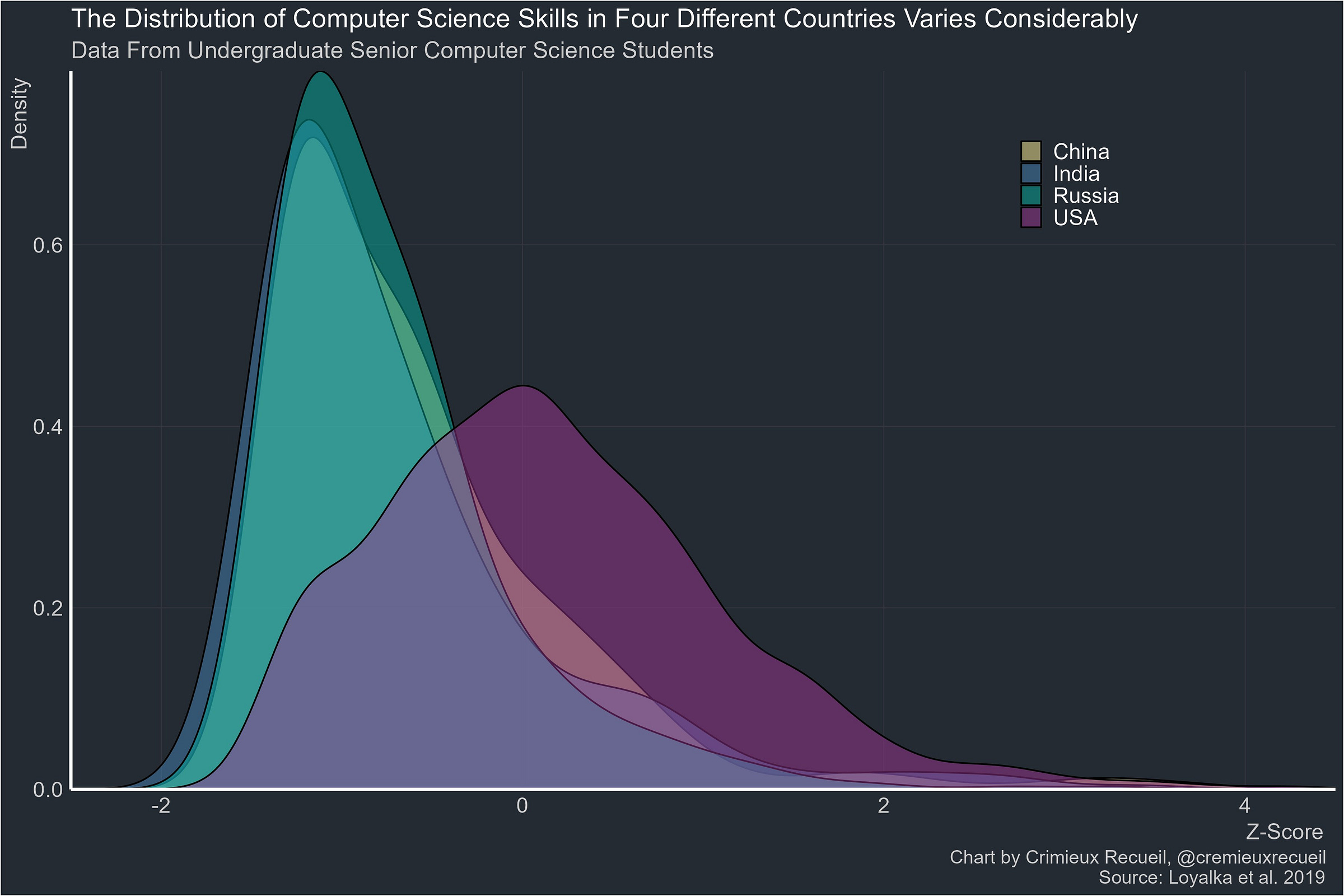

Foreigners are often sought after for the educational credentials they hold in different countries—offshoring services! This is common for a few fields, but a notably high-skilled one is computer science. A revealing 2019 study by Loyalka et al. showed that the educations of foreign computer science students aren’t comparable to U.S. educations.

Loyalka et al. used an expertly translated and psychometrically vetted test of computer science skills and gave it out to thousands of final-year computer science undergraduates across China, India, Russia, and the U.S. Americans far and away outperformed the seniors in ostensibly similar programs in any of the comparison countries:

This skill delta in favor of the U.S. couldn’t be attributed to a high number of international students—if anything, America’s non-international students performed somewhat better—nor could it be attributed to an overrepresentation of elite school attendees in the American sample. At the end of the day, American students just tended to be more skilled, and there’s not even a saving grace in the form of higher variance in China, India, and Russia. In fact, the opposite is true:

But, though American natives are quite skilled relative to both immigrants and their foreign peers who their work might be outsourced to, there’s still another group that needs to be discussed: people who choose to pursue skill development because they want to go to America!

Some economists have recently begun to argue that brain drain—where smart or skilled people leave for another country—isn’t a problem. This argument is a matter of degree. Plenty of people now say it doesn’t exist full-stop and others argue there are offsets, so its harms have to be considerably qualified. The reason brain drain effects need to be qualified is that when skill-based ways to migrate open up, people in sending countries start training, getting educated, and working on their skills so they can become eligible to move. Those countries thus experience “brain gain”