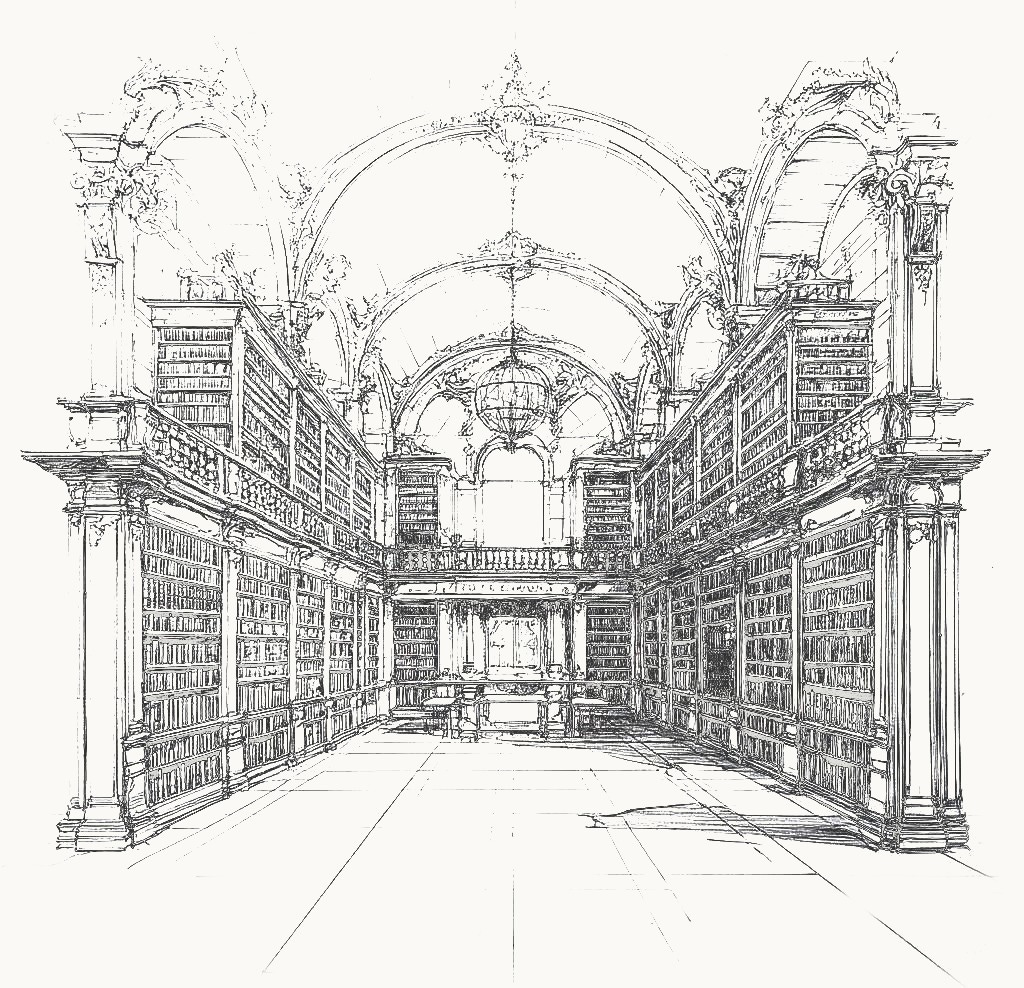

Nestled in a café-bar-museum-event space in Fort Mason — San Francisco’s water-front, weathered military campus with sweeping views of the Golden Gate Bridge —is a floor to ceiling library housing the Long Now Foundation’s Manual for Civilisation. A crowd-curated collection of the 3,500 books “most essential to sustain or rebuild a civilisation,” the Manual for Civilisation began with one question: If you were stranded on an island (or small hostile planetoid), what books would you want to have with you?

The collection, displayed along industrial walls, is both solemn and optimistic, earnest and futile, a romantic’s bookish Golden Record. It is, most vividly, a humbling monument to historian Barbara Tuchman’s proclamation that “Books are the carriers of civilisation.” “Without books,” Tuchman wrote, “the development of civilisation would have been impossible.”

Linking civilisation and human culture to books, reading and writing is not unique to Tuchman.

Writing nearly 350 years earlier, Galileo had declared books “the seal of all the admirable inventions of mankind,” because books allow us to communicate through time and place, and to speak to those “who are not yet born and will not be born for a thousand or ten thousand years.”

A few generations later, Henry David Thoreau, writing in the seclusion of Walden Pond, wrote that “books are the treasured wealth of the field and the fit inheritance of generations and culture.”

The following generation, Carl Sagan, after taking his TV audience on a journey through the cosmos, found himself alone in a library, circling back to Galileo. With the Cavatina — one of two Beethoven songs floating in space on the Voyager II’s Golden Record — playing, Sagan marvelled at the existence of books. “Writing,” he says, “is perhaps the greatest of human inventions, binding together people who never knew each other, citizens of distant epochs.” “A book,” he concludes, “is proof that humans are capable of working magic.”

Tuchman’s platitude, then, has persisted through the centuries: Books carry civilisation. Not because they are inherently sacred objects of inherently sacred knowledge, but because reading and writing assemble and shape culture. And without culture, there is no civilisation.

In Arabic, the root word for civilisation — ح-ض-ر: to be present, to settle, to remain — expresses a profound shift from wandering to dwelling. For Islam, that shift began with a search at the boundary between city and desert.

1,450 years ago, looking down at the Kaaba from 2,000 feet up, and over two miles away, a wanderer in search of a spiritual dwelling was commanded to Read. The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ responded, “I am not a reader.” He was commanded again, Read. Again the Holy Prophet responded, “I am not a reader.” The command came once more. Read in the Name of your Lord who created.

So much has been said about Islam’s origin story — codified through humanity’s most rigorous and sophisticated system of oral preservation — that one hesitates to reference it in an essay about reading. Yet, it is with this divine command that the God of Abraham, Moses and Jesus began the story of Islamic civilisation. Read in the Name of your Lord who created.

To command an unlettered man to Read unsettles the essential pillar that reading is largely, or exclusively, the one dimensional act of decoding printed symbols. The Arabic word, “Iqra,” often translated as to “read” contains a curious ambiguity — it simultaneously means “to read” and “to recite.” To recite is to engage in a primarily oral act, externally expressive. To read is to engage in something more private and solitary, internally reflective.

The Read of Islam’s originating verse embodies, as Alan Jacobs succinctly puts it in Pleasures of Reading in the Age of Distractions, “a moving between the solitary encounter and something more social.” In the context of modern reading, social can be anything — a journal entry, a blog post, a book club, a literary salon, a dignified virtual debate, a letter to a friend — because, Jacobs writes, “every good idea ever achieved is the product of both connection and contemplation, of moving back and forth between the two.”

If reading does not flow outward to build and contribute to the living networks of human knowledge, the divine command to Read feels hamstrung, unfulfilled.

Reading alone however — even with its duality — is not enough. The Quran’s command to read has a direction.

Read in the Name of Your Lord who Created. Created humans from a clinging clot. Read! And your Lord is the Most Generous, Who taught by the pen—taught humanity what they knew not.

The command to Read in the name of our Creator confers — as Rebecca Elson put in “We Astronomers,” a poem about resisting disenchantment — a “responsibility to awe.” The Quranic Read could be interpreted as a responsibility to awe. It is an invitation to learn with both disciplined inquiry, and receptive wonder.

Over the last century, our responsibility to awe has been a source of anxiety.

In 1926 — the year the radio, a dizzying new addition to the American home, brought the World Series to living rooms across the country; the year Bell Telephone perfected transcontinental calls from New York to San Francisco for $18; the year the Orpheum Theatre opened in Los Angeles, its legendary neon sign still shining today—Virginia Woolf worried about the future of reading.

In the August 3, 1926 edition of The New Republic, Woolf, comparing cinema to reading, is unsettled and nearly disgusted by the horror of the cinema. The cinema, she writes, and the pleasure we derive from it, emanates from an impulse so unrefined in its humanity, it is anti-civilisational. Woolf, the quintessential sombre optimist who famously wrote that “the future is dark, which is the best thing the future can be, I think” in January 1915, does not go so far as to condemn the future of reading, but she concludes the audio-visual dangerously erodes depth.

25 years later, in 1951 — the year I Love Lucy debuted, replacing the family radio with a wooden TV box set; the year of House Un-American Activities Committee; the year of the first nuclear tests in the Nevada desert; the last year before the death of technicolour in 1952 — E.B. White, beloved children’s book author of Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little, worries about the future of reading.

In the New Yorker’s “Talk of the Town,” White reflected on the Rollins College President’s prediction that

23 Comments

geff82

Currently re-visiting and re-describing old tumulus tombs in my area where the last survey was decades ago and where no current description exists. Also, I found tombs via Lidar maps that have been unaccounted before and I am cataloguing them. All that as a hobby and as a member of an association of local history.

Things can be done and should!!

mjfl

[dead]

submeta

What a wonderful article! Thanks for sharing!

I’ve been thinking a lot about how research — as both leisure and serious inquiry — is making a comeback in unexpected ways. One sign of that resurgence is the huge interest in so-called “personal knowledge management” (PKM) tools like Obsidian, Roam Research, or Notion. People love referencing Luhmann’s Zettelkasten method, because it promises to structure and connect scattered notes into a web of insights.

But here’s the interesting part: the tools themselves are often treated as ends in their own right, rather than as vehicles for truly deep research or the creation of original knowledge. We end up collecting articles, or carefully formatting our digital note-cards, without necessarily moving to the next step — true synthesis and exploration. In that sense, we risk becoming (to borrow from the article) “collectors rather than readers.”

I read Mortimer Adler’s "How to read a book" 30 years ago. It mentions severl levels of reading-ability. The highest, he says, is “syntopical reading”, which is a powerful antidote to this trend mentioned above. Instead of reading one source in isolation or simply chasing random tangents, syntopical reading demands that we gather multiple perspectives on a single topic. We compare their arguments and frameworks, actively looking for deeper patterns or contradictions. This process leads to truly “connecting the dots” and arriving at new insights — which, in my view, is one of the real goals of research.

So doing research well requires:

1. *A sense of wonder*: the initial spark that keeps us motivated.

2. *A well-formed question*: something that orients our curiosity but leaves room for discovery.

3. *Evidence gathering from diverse sources*: that’s where syntopical reading really shines.

4. *A culminating answer* (even if it simply leads to more questions).

5. *Community*: sharing and testing ideas with others.

What stands out is that none of this necessarily requires an academic institution or official credentials. In fact, it might be even better done outside formal structures, where curiosity can roam freely without departmental silos. In other words, anyone can be an amateur researcher, provided they move beyond the mere collection of ideas toward genuine synthesis and thoughtful communication.

tokai

Don't buy it at all. Global book market is healthy and as big as it ever was. Most of us a reading more in a day that even scholars did in a month two centuries ago. It has never been more accessible to research any kind of subject and phenomenon than it is now.

The article is rolling out the same old bourgeois doomsday theory people like Stefan Zweig and McLuhan subscribed to. Luckily the democratization of literacy or even leaving the medium of the book behind is the opposite of an issue.

thriw7383848

[flagged]

bsindcatr

I perused the three posts on this blog, and believe that an LLM was heavily used, because I used one daily, and this is the way its content reads.

The leisure the author speaks of may be their own, and the research of which they speak today may be done by a machine.

I think the intent is good, and if you as the reader get insight from it, then it is still valid, but I cannot read it, because I don’t feel a thread of consciousness helping me experience life with them.

If an author chose to instead pair with an LLM to research on their own and write themselves about it, perhaps it would be different.

Why do these posts keep getting to the front and even to the top of the HN feed? We are no better than machines, I guess.

dynm

One of the underrated downsides of the professionalization of research is how much it sucked the "fun" out of things. It's strange, but research papers in most fields are written very differently from how people actually talk to each other. Professional researchers still communicate informally like normal humans, in ways that are "fun" and show much more of how they came up with ideas and what they are really thinking. But this is very hard for outsiders to access.

brightball

I started reading history as a hobby a few years after college when I heard some things from people that just didn’t make sense or didn’t seem true. So I picked up a booked that was well cited, read it while checking the citations after each chapter. Between the Library of Congress and Google, checking original sources has never been easier.

It was a really mind blowing exercise. Much more interesting than fiction.

When I do Bible study now I do it the same way, find whatever sources I can to cross reference with other history at the time. Strongly recommend it.

What’s funny is that history is the subject I was least interested in all through school.

thehyperflux

I do a ton of product research for leisure…

markus_zhang

Don't know about you guys, but reading has become more and more of a burden for me.

It is as if — I have greatly narrowed my interest such that most books are not interesting any more. Even the sci-fi and fantasy books, once I loved, lost their magic.

Nowadays there are only two types of books that excite me: 1) those about software/hardware engineering, such as iWoz(I even bought a few Tom Swift JR books for my son), Showstopper and Soul of the New Machine, and 2) books about existentialism such as Shestov's philosophy books.

I suspect it has something to do with getting older and getting kid(s).

What about you guys?

NalNezumi

The blog post gives a slight posh impression. With the excessive quoting of authors and their book but in an incoherent manner that only strengthen the authors narrative by "look many famous people agree with me" and not why they agree with you.

I agree with the general sentiment of the article but I think it kinda defeat itself in its need to reaffirm it's own excellence over actually being informative. He could've skipped everything above the "Against hollow reading" Section and got the same message across.

The message below that section is valuable but only in value. It doesn't really get in to how to practice it. It laments the modern information landscape but doesn't tell us how. His point can be summarized to "don't be a passive consumer of information, be active in asking questions, refine those questions, and develop answers".

How? Write. Write for leisure, not for anyone else but yourself and read it with critical lenses you use when reading others. Only then will you need to refine your writing and thinking, which leads to new questions, new exploration and perspective.

Research of any kind is an iterative process. You find new information, you create a bias in favor of it, try to explain many things with it. Then you realize that it doesn't explain everything, and now you have to go back to reading or finding out more. It's easier to catch yourself getting stuck with one idea, when you write those down and review them. Reading as he put it, the introspecting one is only complete when combined with Writing. (Or at least deep contemplation that resembles the structure of writing)

This article reminds me of "I don't like honors" by Richard Feynman[1]. Too caught up in how one ought to be, rather than being (or informing).

[1] https://youtu.be/iNCiQzMDcV0?feature=shared

sergioisidoro

I think reading is an essential skill, but we also need to get reading out of the pedestal. Because a lot of the time these arguments come across as some sort of literary elitism. Like if you're not ingesting information through reading, it doesn't count.

This month I spent many hours listening to lectures on youtube about geopolitics on the Asian continent from the naval war college. Sure I could have read it, but nevertheless I got curious about a topic, engaged in it, and "followed the rabbit holes"

I think there is a case to be made that we need to be more active in information seeking, rather than just being fed what the algorithm suggests you – on that topic Technology connections recently made a really good exposition of that issue — https://youtu.be/QEJpZjg8GuA — But it should not be about the method of ingesting information, but the quality and the intent of it.

atebyagrue

This article sums up precisely why I don't mind being a "forever GM".

I'm constantly researching new things to flesh out game ideas for my groups to add flavor, immersion & a sense of "reality" to my players' worlds & I love doing it. It almost makes running the actual games for them, an afterthought to tide me over to the new thing to learn about & implement. Great article!

janpmz

I did some leisure research on how the Nazca Lines align with mountain shadows and made a publication. That was a nice weekend.

https://zenodo.org/records/11422308

jsemrau

“I have studied, alas, philosophy, jurisprudence and medicine, and even, sad to say, theology, all with great exertion.”

– Faust, Part I, Scene I (“Night”)

btrettel

I only skimmed everything before "From Theory to Practice: A Framework for Research as Leisure" and read everything after that, but it doesn't seem this covers actual obstacles to doing research on the side that I face. I do want to note that to the author, "research" seems to be basically a learning process, whereas I'm interested in building something, which I think is more involved. Here's my perspective on the obstacles towards this form of deeper research:

1. Lack of time and energy. This to me is the largest obstacle for any of the research side projects I've had since finishing my PhD. My day job gets the best of my time and energy and everything else gets scraps. What I do on the side tends to be more superficial than I'd like for this reason. (More specifically: Lots of reading and writing, little implementation of my ideas.) I simply don't have the energy to do much deeper work. I recently concluded that to make progress on the one side project I'm prioritizing, I'm probably going to have to take leave from my job. And it's also been necessary to think like a startup, to limit the scope and focus on a MVP. But even the MVP is still challenging.

2. Intellectual property assignment agreements. A lot of technical folks' employers made them sign agreements that arguably give the employers' full rights to what their employees do in their free time. If I'm working on a side project that could turn into a business, it's simply risky if my employer could swoop in and claim ownership of the entire thing. I think even the "favorable" versions of these agreements that limit what employers can take to things related to what the company does are still overreach. A lot of companies do tons of things and could find justification to take nearly anything for that reason.

3. Lack of collaborators and community. I think the linked article discusses "community of knowledge" in a superficial way. I haven't tried, mind you, but I think it would be really hard to find a group of people online with similar research interests to mine. I think people who have more common or less specific interests would not have a problem, but for anything more specific, finding collaborators is going to be a challenge. I think I won't find a close collaborator until I publish something (could be journal article or even a web page) and they come to me.

DeathArrow

It would be nice to afford to practice that art. Most people are practicing the art of putting food on their tables.

Most researchers are doing it for a living and they might want to pursue other activities in their free time. Other people do not possess the skill level. Science and research is harder than it was centuries ago.

brador

The fact that all historians still refuse to acknowledge the origin of the term “yankees”.

jdp

Stamp collecting is a good outlet for research as leisure. If you're the type of person who falls into wiki holes and likes talking about what you learn with other people, it might be for you.

Many stamp collectors follow the research-as-leisure framework naturally as part of their hobby. The article outlines cultivating curiosity, developing questions, gathering evidence, developing answers, and building communities around that process, which is basically what collectors are doing when they're talking about stamps and other philatelic material. They're sharing discoveries they find interesting, often only after identifying the material, looking up its historical context, drawing parallels to current events, and then formulating some kind of answer or conclusion that makes it worthwhile to share what they've found.

I think the experts in a lot of hobbies engage in this sort of recreational research for the joy of it, but it's closer to the norm for casual collectors. There is a whole wide spectrum of collectors though, ranging from aesthetics-driven folks who spend more time on thematic album pages than on researching anything, over to experts in narrow areas like Transylvanian hotel stamps who publish whole books on about how they weren't valid for postal use but were used by hospitality workers nestled up in the Carpathians to get mail from guests back into the official mail stream because the state couldn't be bothered to service up there. If you get into it you'll find there are a lot of curious and motivated people in the middle who are happy to share what they've been reading about (or listening to, or watching) lately.

calvinmorrison

Join the RR&R or start your own charter club!

https://ephorate.org

inktype

I'm sure it's still out there, but I don't seem to notice as much prevalence of dedicated research trivia as I used to, like Damn Interesting, or Cracked. Lots of the articles would be some niche question that wasn't just a google away and it was obvious that it took effort and time at a library to write.

The closest thing that comes to mind now is Asianometry's youtube channel and mailing list.

awongh

I read a fair amount and I actually do research as leisure all the time, but I can’t stand these elitist and unoriginal think pieces about how much better and cooler this person’s habits are than yours.

>> for the leisurely researcher, self-study must include the discipline’s foundational texts

I feel like this person has some kind of dark academia aesthetic fetish that they need to hold onto to feel superior to everyone else.

I actually deeply agree with the advice in the OP around curiosity but personally I end up implementing it in a totally different way than they do.

Lately I’ve found that LLMs are an amazing tool for this free-floating “research”- for example “Summarize the top three theories about why suburbs exist and who said them”. The LLM as open ended semantic search engine / research tool is an amazing way to figure out the topology of a subject you want to dive deeper into.

I usually work my way down a content ladder from there to podcasts, wikipedia and finally to books.

The idea that somehow civilization is ending because of our media consumption habits and that “reading source material” will save us comes off as more an aesthetic fantasy than a real-world complaint about today’s culture.

I was around before the internet and I’m so thankful that so much more information is accessible now than it was when there were only books.

fxtentacle

"Where have the amateur researchers gone"

To their 2nd job.

"and how do we bring them back?"

Pay them enough salary to survive on just 1 job.