It has been a subject of much recent internet discourse that the kids are not okay. By all reports, the kids very much seem to be not all right.

Suicide attempts are up. Depressive episodes are way up. The general vibes and zeitgeist one gets (or at least that I get) from young people are super negative. From what I can tell, they see a world continuously getting worse along numerous fronts, without an ability to imagine a positive future for the world, and without much hope for a positive future for themselves.

Should we blame the climate? Should we blame the phones? Or a mind virus turning them to drones? Heck, no! Or at least, not so fast.

Let’s first lay out the evidence and the suspects.1

Then, actually, yes. Spoiler alert, I’m going to blame the phones and social media.

After that, I’ll briefly discuss what might be done about it.

Suicide Rates

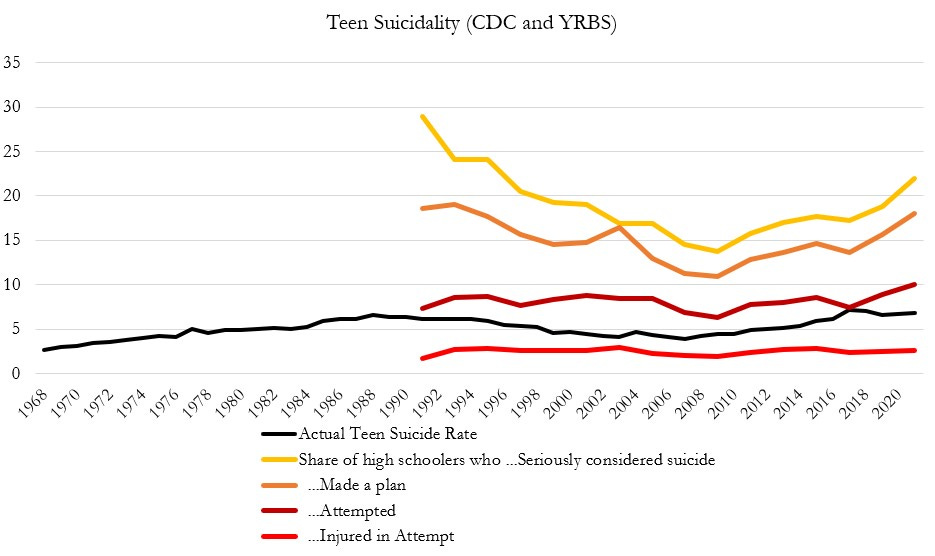

The suicide numbers alone would seem at first to make it very very clear how not all right the kids are.

Washington Post reports, in an exercise in bounded distrust:

Nearly 1 in 3 high school girls reported in 2021 that they seriously considered suicide — up nearly 60 percent from a decade ago — according to new findings from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Almost 15 percent of teen girls said they were forced to have sex, an increase of 27 percent over two years and the first increase since the CDC began tracking it.

…

Thirteen percent [of girls] had attempted suicide during the past year, compared to 7 percent of boys.

One child in ten attempted suicide this past year, and it is steadily increasing? Yikes.

There is a big gender gap here, but as many of you already suspect because the pattern is not new, it is not what you would think from the above.

In the U.S, male adolescents die by suicide at a rate five times greater than that of female adolescents, although suicide attempts by females are three times as frequent as those by males. A possible reason for this is the method of attempted suicide for males is typically that of firearm use, with a 78–90% chance of fatality. Females are more likely to try a different method, such as ingesting poison.[8] Females have more parasuicides. This includes using different methods, such as drug overdose, which are usually less effective.

I am going to go ahead and say that if males die five times as often from suicide, that seems more important than the number of attempts. It is kind of stunning, or at least it should be, to have five boys die for every girl that dies, and for newspapers and experts to make it sound like girls have it worse here. Very big ‘women have always been the primary victims of war. Women lose their husbands, their fathers, their sons in combat’ (actual 1998 quote from Hillary Clinton) energy.

The conflation of suicide rates with forced sex here seems at best highly misleading. The sexual frequency number is rather obviously a reflection of two years where people were doing rather a lot of social distancing. With the end of that, essentially anything social is going to go up in frequency, whether it is good, bad or horrifying – only a 27 percent increase seems well within the range one would expect from that. Given all the other trends in the world, it would be very surprising to me if the rates of girls being subjected to forced sex (for any plausible fixed definition of that) were not continuing to decline.

That implies that in the past, things on such fronts were no-good, horribly terrible, and most of it remained hidden. I do indeed believe exactly this.

Also, can we zoom out a bit? On a historical graph, the suicide rate does not look all that high (scale is suicides per 100,000 children, per year)?

The kids are not okay. The kids in the 1990s were, by some of these graphs, even more not okay. The kids in between were also not okay. It’s not like 14% is an acceptable number of kids seriously considering suicide in a given year, or 7% an acceptable rate of them attempting it. But those kids, by these measures, were less not okay.

CDC Risk Study

We also know that the rate of major depressive episodes among US adolescents increased by more than 52 percent between 2005 and 2017. I do think some of that is changing norms on what we call such an episode. I doubt that is all (or more than all) of it. That problem still seems sufficient to make farther-back comparisons not so meaningful, and make me want to fall back on suicides, similar to the case count vs. death count question in measuring Covid.

Here is the CDC study of youth risk behavior.

They are happy to report several things. Adolescents are engaging in less ‘risky sexual behavior,’ which means less sexual behavior period, both at all and with four or more partners. There is less substance (alcohol, marijuana, illicit drug, misused prescription drug) use.

(Rough math aside: In case anyone was wondering, yes, sexual contacts and alcohol use go together. If 30% of students have had sex and they are 41% likely to be drinking, and overall rate is 23%, that means only 13% of virgins are drinking, over a 3:1 ratio. For illicit drugs, 25% vs. 7.4%. And for marijuana, this it’s 34% vs. 8.3%, over 4:1, so looks like hard drugs are bad even on their own terms.)

Overall: So less fun. Sounds depressing. Less sexual activity is flat out called ‘improvement’ by the CDC. I am going to come out and say that the optimal amount of teenage sexual activity, and the optimal amount of teenage substance use, are importantly not zero.

They also talk glowingly about ‘parental monitoring,’ defined as parents or other adults in their family knowing where students are going and who they are with, as ‘another key protective factor for adolescent health and well-being.’ While I certainly would agree with the correlation with short term physical safety, and that this leads to less sexual activity and substance use, I would centrally say that considering this a key protective factor is one of the prime suspects for reasons kids are depressed so often.

On the plus side, there was also less bullying.

They are less happy to report worse overall mental health, more suicidal thoughts and more suicidal behaviors, as already noted. There is less condom use, less STD testing and less HIV testing, which is what rational people would do given less sexual promiscuity and improved treatments available for HIV.

(On another note, this below has to be the weirdest stat I’ve seen, I keep trying to figure out what it could mean and coming up short.)

If you look at the above graph, you’ll notice that HIV testing is not declining once you control for rates of sexual activity. The decline in condom use is entirely explained by the decline in multiple sex partners combined with selecting responsible teens out of the dating pool. If we had access to ‘the crosstabs’ we could check if this is indeed what is happening.

They also observe a rise in ‘experiences of violence.’ When I saw that I noted I was outright calling BS on any real effect. To the extent that ‘experiences of violence’ are rising, it is about what people are told to report experiencing changing, not about any increase in real physical violence. Then I found the actual stats on page 46:

I mean that’s some bounded distrust right there. Is this an increase in violence? The only substantial increase here is not going to school because of safety concerns. I am happy to report that safety concerns are not violence. Actual safety concerns in a school surround bullying, which is down (and I’d heavily bet is down in severity too). What do we do about that? I mean, same as we always have, and hint it isn’t letting them miss school. We force students who are being beaten up by other students into close proximity with their bullies at the barrel of a gun, of course. What else would we do?

Also, seriously, no increase in electronic bullying since the introduction of the smart phone, are you kidding me? How is this even real? How did we do it? Huge if true.

Also I will state that ‘did not go to school because of safety concerns’ did not change between 2019 and 2021 and let that float around in everyone’s head for a bit.

There are a bunch of other ‘are you seriously saying this trend went this way during the pandemic?’ stats and I will spare you the rest of them.

On to their depression stats, which match other sources.

I am curious about the 13% or more who experienced persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness without poor mental health. If I was feeling persistently sad or hopeless and someone asked me for the quality of my mental health, and I had the energy to reply, I would reply ‘poor, thanks for asking.’

Strangely, they list suicide considerations, plans, attempts and injuries, but do not list stats on actual suicides.

Objectively Worse?

This New York Magazine article says that ‘No, Teen Suicide Isn’t Rising Because Life Got Objectively Worse.’ It does confirm that the lived experience of teens seems to have gotten worse, at least in terms of their mental health.

Life isn’t ‘objectively worse,’ in this view, because the economy has improved as has our social safety net. Our treatment of many groups has dramatically improved. If you are entering the labor force today, goes the argument, you can expect to earn a much higher ‘standard of living’ than your predecessors in the 1950s. Suspicion is pointed towards our phones and social media.

I would suggest this misunderstands what it means for things to be ‘objectively worse.’

Economically one should emphasize the ability to purchase a socially acceptable goods basket that enables the important aspects of life, more than worrying about the measured quality of its components.

Similarly, I would assert that the existence of social media can absolutely make things ‘objectively’ worse if it works like its critics fear, as can all the other suspects one might have. To the extent one disagrees with this, the word ‘objective’ is being used to dismiss concerns other than access to material goods as not ‘objective.’

If you want to use that definition, fine, you can use that word in that way. In which case I do not much care whether the ‘worse’ is ‘objective.’

(Also, you can’t both assert factors like ‘tolerance for many groups is way up’ as objectively good and then reject factors like ‘tolerance for not using social media is way down’ as not objectively bad. Both are real, and they are equally ‘objective.’)

That does not tell us what is causing the kids to not be okay. It does make it less likely that we should be looking mostly or exclusively at social media, or at wokeness, or fear of climate change, since none of those can explain the early 1990s. That would require the two peaks have distinct causes.

Children Versus Adults

Should the cause differentiate adults from children? Adults continue to say they are happy with their own lives despite not being happy with things in general (source). To the extent that their happiness with things in general changed, it does not correspond at all to when the kids were relatively not okay.

All the usual suspects correlate, in case anyone is pretending they don’t.

An alternative hypothesis is that perhaps adults are happy with their lives largely relative to the baseline of what they see as the lives of others around them, rather than as an absolute thing. Being more worried about losing one’s job makes you not okay, but it could also make you more satisfied with the job you do (at least for now) have. You can see 2008 on the personal satisfaction line, but it is a rather small effect. Whereas kids perhaps have not learned these tricks so much yet, and only observe that things are not okay.

School Daze

A reasonable suspect for the core problem would be American schools. Remember that suicide rates go up during school, go down during summer vacation. When there were school closings, suicide rates declined.

Robin Hanson thinks this is clear, responding to the new paper reported via MR to have shown a negative log-linear relationship between per-capita GDP and adolescent life satisfaction.

If a group is attempting suicide this frequently, reports of life satisfaction this high do not make sense unless they represent comparison to expectations, or to the lives of others. We need to look for a better understanding of what such responses mean.

The problem with the school hypothesis is that while it explains kids not being okay in general, it does not explain the changes over time. If you buy as I do the hypothesis that our schools have been making kids miserable, why would that effect have gone down and then gone back up again?

I can tell a story for why school was especially toxic during the pandemic. ‘Remote learning’ was a new level of dystopian nightmare. That still does not fit the graphs.

I can tell a story where recently schools have become more controlling and restrictive, perhaps more woke and liable to alarm kids regarding climate change or gun violence, they interact in toxic ways with social media. Heck, they’re doing mandatory trauma infliction periodically, which they call active shooter drills.

That all seems like it doesn’t sufficiently differentiate school from these other candidate source factors, and we would still need a second story for how those things had local peaks in the 1990s, which doesn’t seem right.

Thus I would say that school lays the foundation for children to be miserable. I would say school directly causes children to be miserable. It still does not seem to explain why things recently got so much worse.

Liberal Politics

Matt Yglesias suggests we look at politics, and why young liberals are so much more depressed than young conservatives. He points to a study looking at depression in adolescents by political beliefs.

I notice that this graph is suggesting something happened around 2011 that impacted everyone, and disproportionally impacted only liberal girls. Until then, liberal girls and liberal boys had similar depressive levels. Even now, conservative boys and conservative girls are similar, and the temporary difference ran the other way. The conservative vs. liberal gap among boys is similar in 2005 and 2018.

The story this data is telling is something like:

- Liberal children are more often depressed than conservative children.

- Since 2005, depression among children has risen across the board.

- Since 2005, something has made liberal girls in particular more depressed.

Causation between politics and depression is not obvious here. All of these stories seem plausible:

- If you are depressed, that tends to make you liberal. Change is needed.

- If you are liberal, that tends to make you depressed. Change is needed.

- If you are liberal, you tend to identify as depressed more often.

- If you are attending liberal-area school, you’ll report depression more often.

- If you are around liberals more in person, you’ll report depression more often.

- Liberal parents are raising their kids in ways that cause more depression, and kids tend to adopt the ideologies of their parents.

- Urban areas lead to greater risk of childhood depression, and are liberal.

A left-wing theory by authors of a paper on the subject of why this is happening is that it is all because bad political actors are doing bad things, which are very depressing if you are a good person who understands. I’ll quote the same passage as Yglesias does, except for spacing:

Adolescents in the 2010s endured a series of significant political events that may have influenced their mental health.

The first Black president, Democrat Barack Obama, was elected to office in 2008, during which time the Great Recession crippled the US economy (Mukunda 2018), widened income inequality (Kochhar & Fry 2014) and exacerbated the student debt crisis (Stiglitz 2013).

The following year, Republicans took control of the Congress and then, in 2014, of the Senate. Just two years later, Republican Donald Trump was elected to office, appointing a conservative supreme court and deeply polarizing the nation through erratic leadership (Abeshouse 2019).

Throughout this period, war, climate change (O’Brien, Selboe, & Hawyard 2019), school shootings (Witt 2019), structural racism (Worland 2020), police violence against Black people (Obasogie 2020), pervasive sexism and sexual assault (Morrison-Beedy & Grove 2019), and rampant socioeconomic inequality (Kochhar & Cilluffo 2019) became unavoidable features of political discourse.

In response, youth movements promoting direct action and political change emerged in the face of inaction by policymakers to address critical issues (Fisher & Nasrin 2021, Haenschen & Tedesco 2020). Liberal adolescents may have therefore experienced alienation within a growing conservative political climate such that their mental health suffered in comparison to that of their conservative peers whose hegemonic views were flourishing.

To me and to Matthew Yglesias, this sounds like a story of political discourse among and directed to young people making them depressed.

This is not plausibly a story about a society that was suddenly overcome by a huge rise in war (which wars is this even claiming to be talking about given the time frame, I seriously have no idea?) or any of the other non-economic factors. For economics, the timing does not match, nor is there any reason bad economic prospects should depress liberals but not conservatives during a period where both parties took turns in political office.

This is instead a story about how these bad things became central and constant parts of the discourse that young people felt socially obligated to discuss and endorse. As the authors say, they became ‘unavoidable.’

Young people in liberal peer group social circles – which is most young people, especially given the internet – were increasingly socially punished for not expressing the view that a lot of extremely depressing things were happening. Social media amplified this quite a lot. The youth both had to endorse that these things were depressing and terrible and unacceptable, focusing carefully on the current thing of the week, and signal that this depressed them, and also express the belief that these things were getting worse.

That certainly sounds like it would cause a lot of depression, regardless of the truth the claims subject to these social cascades.

Regardless of the extent to which these issues are central, I highly endorse not catastrophizing, and not encouraging others to catastrophize.

These last few weeks, I have written two giant posts covering events that Isee as plausibly leading directly to all humans being killed and the wiping out of all value in the universe. I have seen the richest man in the world announce his intention to do the worst possible thing he could do, to make the problem arrive faster and be that much harder to solve. Whether or not you (or most others) agree with this perspective on recent events in AI, it is my perspective, yet I do my best to (mostly successfully) keep smiling.

It is important to cultivate the skill of not letting such things bring you down, and to encourage a discourse and culture that helps others not be brought down rather than reinforcing such failure modes.

Whereas, as far as I can tell, liberal discourse explicitly reinforces not doing that.

Another aspect of liberal politics is the focus on various forms of identity, including demands for how kids must react to things and then potentially severe punishment if caught reacting the ‘wrong’ way, except for the hot and popular kids who of course react the way they always have and get away with it.

All of this is also plausibly very not good for kids’ mental health, and plausibly much more not good than the (also not good) traditional versions.

Then there is the tendency to medicate children every time they get out of line or pose any sort of problem, or are given any kind of label that needs fixing – you can imagine why worries about this happening could make one paranoid and unhappy. Also the drugs themselves often make kids unhappy.

I had a rough childhood in many ways. I never got any sort of formal diagnosis, and was never put on medication. Whatever other things I might be mad about, I am deeply grateful for both of these things.

These days? Not a chance. There is more to say here, but I would leave it as an exercise to the reader.

Phones and Social Media

The Social Media Hypothesis (SMH) is both common and common sense. It is easy to see why we might expect social media to be (1) damaging to everyone, (2) especially damaging to teenagers, (3) even more damaging to girls and (4) extremely difficult to escape even when you know about the problem.

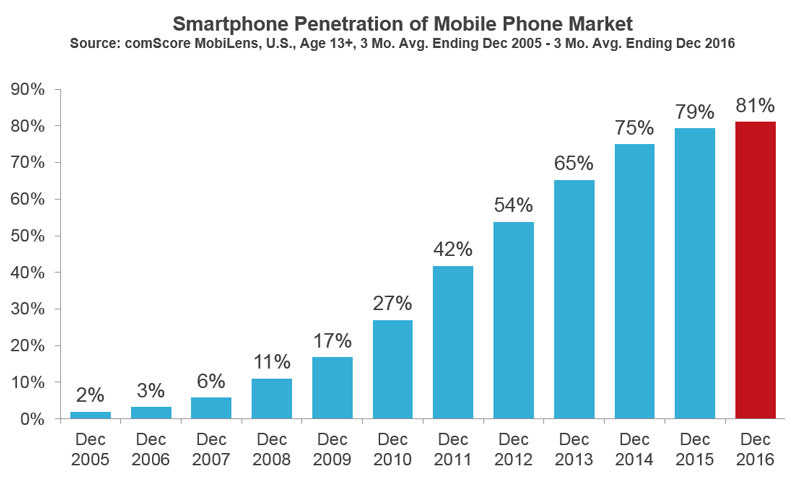

The timing also matches quite well, although it obviously can’t explain the 90s.

Richard Hanania considers the SMH. He notes that given his other views he has strong motivations to reject the SMH and instead blame anything else and especially to blame wokeness. Despite this, he is convinced:

After looking at various kinds of evidence, however, I have changed my mind. This essay sets out to explain why I think that the rise of social media has had disastrous effects on the mental health of young people. First, randomized control trials show that quitting or cutting back on Facebook is good for your mental health. It’s true that some studies show a null or even opposite effect, but, a