This week was gaming week at The Diff, a look at one of the world’s most important media industries and what other companies can learn from it. Posts you missed:

-

AppLovin’s Double-Pivot: AppLovin was born as an app developer, then turned into a tool for marketing apps, and is now transitioning into a hybrid model where they use the information they get from working with app developers to build platonic ideals in certain categories, and then use the data from those apps to better inform their marketing for others.

-

Every Channel, Every Model: There is no end to the devices on which games can be played or the ways they can produce revenue.

-

Xbox: The Misfit: of all the important players in gaming, Microsoft is one of the most surprising. Why does a company that’s dominant at selling to businesses also want to sell video game hardware—and to spend almost $70bn to acquire Activision Blizzard?

Sign up now to read these posts and to access future subscribers-only content. Next week’s coming attractions include a look at a beaten-down growth company, and thoughts on how to run a 10,000-year endowment fund.

Welcome to the Friday edition of The Diff! This newsletter goes out to 27,153 subscribers, up 100 from last week. In this issue:

-

The Factorio Mindset

-

The Carbon Rally

-

The Bridge

-

Housing and Rates

-

Full Stack Media

-

Buying Out Contracts

-

Diff Jobs

This week was Games Week in The Diff. After looking at games’ pricing and distribution strategy, AppLovin’s full-stack/full-lifecycle approach to monetizing, and Microsoft’s defensive investment in Xbox, it’s worth zooming out to consider what impact games beyond the direct economics of the business.

The Factorio Mindset

I used to be of the opinion that the computer game Factorio was a colossal waste of talent, burning many billions of dollars of GDP every year. It seemed downright pathological that Shopify lets employees expense it. If anything, my view was that Amazon should be reimbursing Shopify employees for playing.

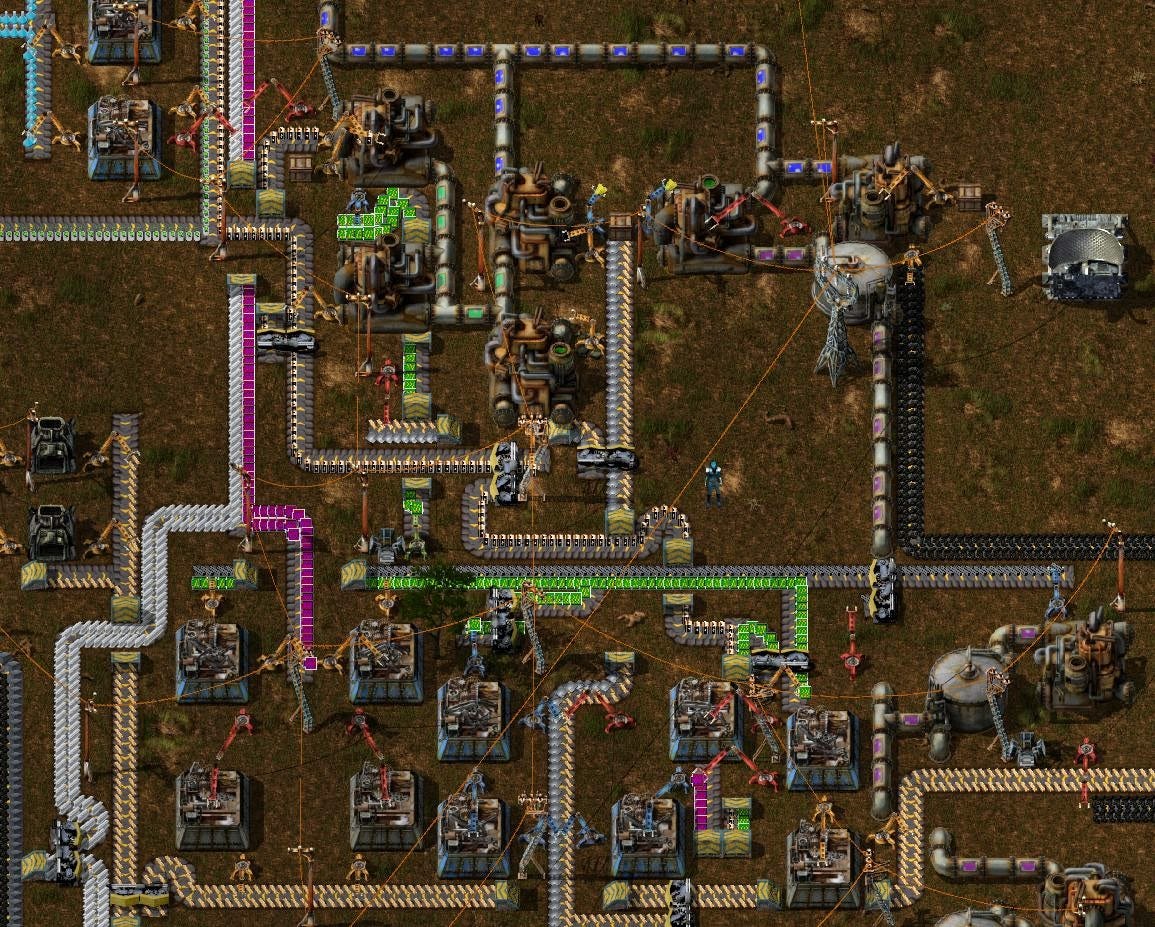

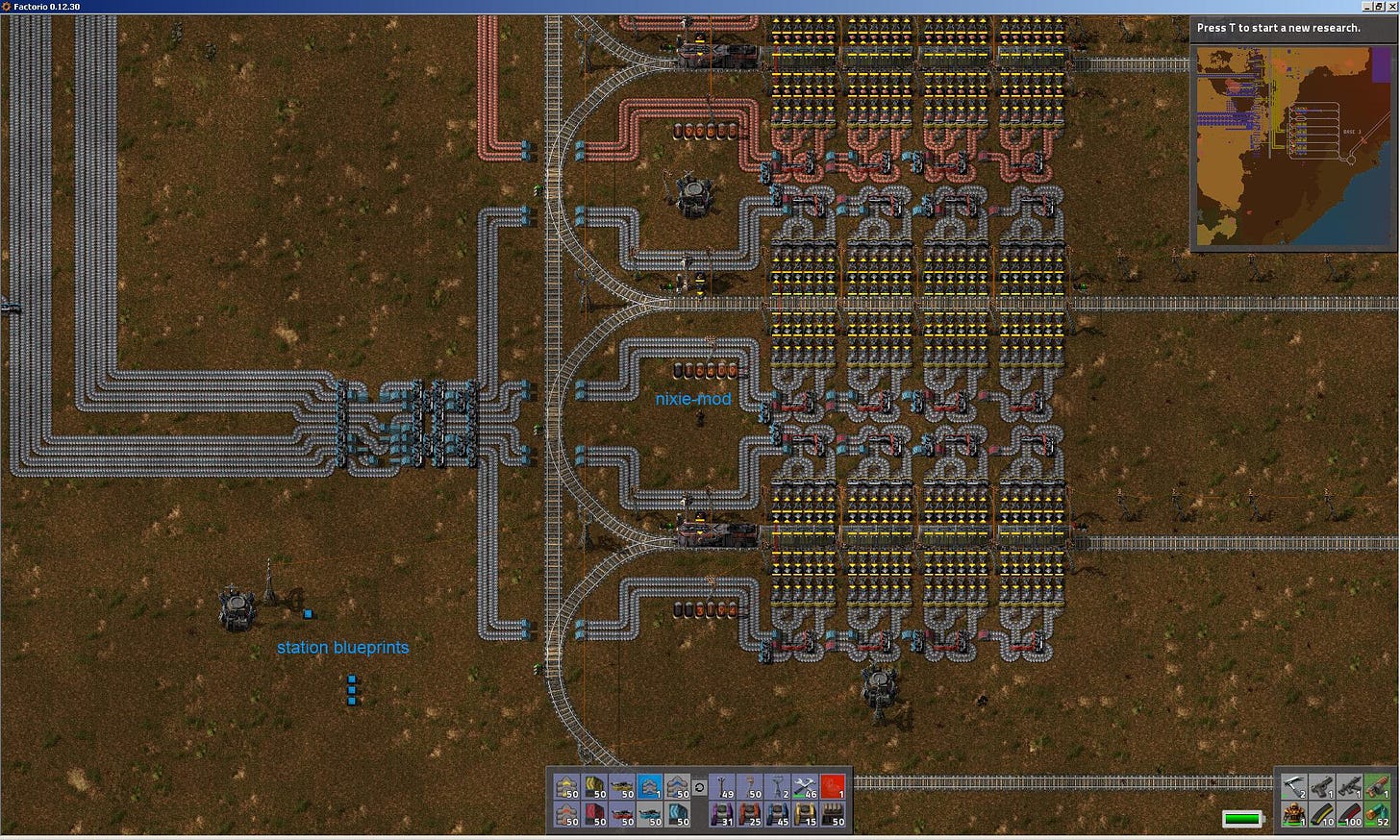

But since trying it out a bit more I’m starting to suspect that Factorio is the rare computer game to actually increase GDP. In Factorio, players gather resources and craft items, and then automate this process—so a player might start by manually mining coal and iron, then smelt the iron and use it to build a mining drill, the hook up some conveyor belts so the miner automatically sends the iron to a smelter, then hook up conveyor belts to that and uses them to pass these materials on to a factory that mass-produces more conveyor belts, mining drills, and so on.

This may sound boring, but how many human-hours per year are spent matching colored gems? Some games get described as meditative, and that’s true of Factorio in two senses: first, there’s a theme-and-variation aspect to it, where each new product built is some combination of known problems (e.g. one more thing to move on conveyor belts) and new challenges (squirting fluids through pipes, and combining their outputs with solid products to create new items). But it’s also meditative in the sense that meditation is partly a way to cultivate a particular mindset, and Factorio does that, too. You can meditate in order to be in the moment; you play Factorio in order to habituate yourself to never leaving a manual process un-automated.

Over time, playing the game reveals the metagame: early factories end up poorly laid-out, with redundancies, complex hacky ways of moving products around, and dead ends from which it’s impossible to scale. So the basic loop in the game is:

-

Make a series of design decisions that have some internal logic at the time, but with accruing mistakes.

-

As you scale, see the consequences compound and necessitate increasingly hacky solutions.

-

Rip up large fractions of the setup and lay them out again with more straight lines and sensibility

-

Go to 1, but making the next round of errors subtler, meaning that the complications are correspondingly hard to fix.

The traditional programming term for solving this kind of problem is “refactoring,” when you take a big messy blob of code that has evolved over time, write down what it is actually supposed to do, and rewrite something that does exactly that.1 Factorio involves a lot of this (it should probably be renamed “Refactorio”). The player is basically building a giant mesh of in-game APIs (“plug in here to get steel bars, plug in there to get green circuits”), getting those APIs to 100% reliability, and then building something on top of them and getting that to perfect reliability, all while managing scarce resources and dealing with random failures.2

This metagame also has some of the flavor of memory management, both in the directly analogous sense that there are finite resources that have to be allocated to different tasks, and in the more metaphorical sense that one of the limits to sloppy scaling is losing track of what you’re working on. Building something that isn’t resource-constrained is one task, and building something that doesn’t overproduce anything of significance is another, more complicated task—but one that’s also rewarding, because it makes the problem so easy to keep track of. Ineffective scaling in Factorio can reach a point where players can in principle keep going, but would in practice need to track an elaborate to-do list; in that case, they lose by turning a game into a chore.

There are many games that evolve into a metagame; ches