When you look out at the Universe, what you see is only a tiny portion of what’s actually out there. If you were to examine the Universe solely with what’s perceptible to your eyes, you’d miss out on a whole slew of information that exists in wavelengths of light that are invisible to us. From the highest-energy gamma rays to the lowest-energy radio waves, the electromagnetic spectrum is enormous, with visible light representing just a tiny sliver of what’s out there. At shorter wavelengths and higher energies, gamma rays, X-rays, and ultraviolet light are all present, while at longer wavelengths and lower energies, infrared, microwave, and radio light encodes a wide variety of information about what various astrophysical sources are doing.

However, there’s an entirely different method to measure the Universe: to collect actual particles and antiparticles, a science known as cosmic ray astronomy. For more than a decade, astronomers have seen a signal of cosmic ray positrons — the antimatter counterpart of the electron — that they’ve struggled to explain. Could it be humanity’s best clue toward solving the dark matter mystery? While many hoped that the answer would be “yes,” a recent study definitively says no, it’s probably just pulsars. Here’s why.

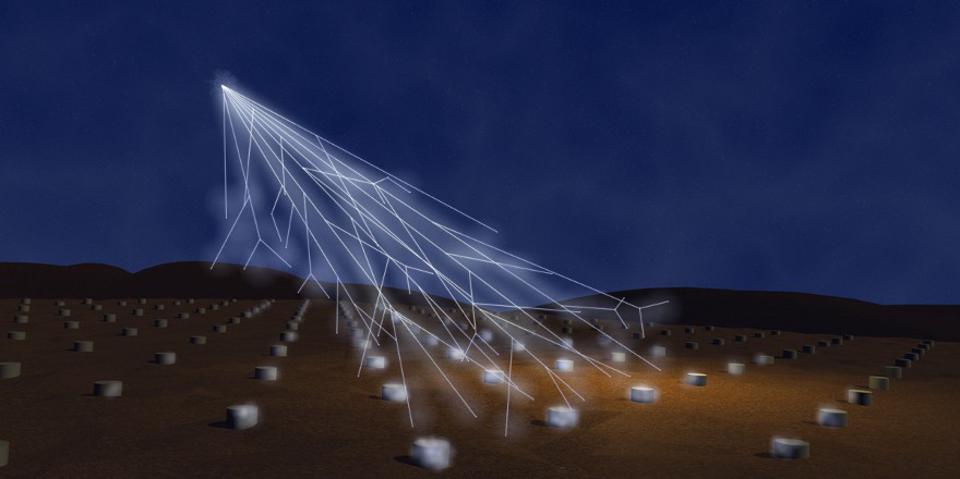

Cosmic rays produced by high-energy astrophysics sources can reach any object in the Solar System, and appear to permeate our local region of space omnidirectionally. When they collide with Earth, they strike atoms in the atmosphere, creating particle and radiation showers at the surface, while direct detectors in space, above the atmosphere, can measure the original particles directly.

There are a great many things in the Universe that are known to create positrons: the antimatter counterpart of electrons. Whenever you have a high-enough energy collision between two particles, there’s a certain amount of energy that will be available with the potential to create new particle-antiparticle pairs. If that available energy is greater than the equivalent mass of the new particle(s) you want to create, the available energy as defined by Einstein’s famous equation, E = mc², there will be a finite probability of generating those new particles with every such collision that occurs.

There are all sorts of high-energy processes that can lead to this type of energy becoming available, including:

- particles accelerated by black holes,

- high-energy protons colliding with the galactic disk,

- or particles accelerated in the vicinity of neutron stars.

However, it’s also possible that they could arise from an exotic source, such as dark matter or a different sort of new particle from beyond the Standard Model. Based on the known physics and astrophysics of the Universe, however, we know that a certain amount of positrons must be generated irrespective of any new physics. “New physics” should only be considered if the amount of positrons generated by the more mundane physical mechanisms is shown to be insufficient.

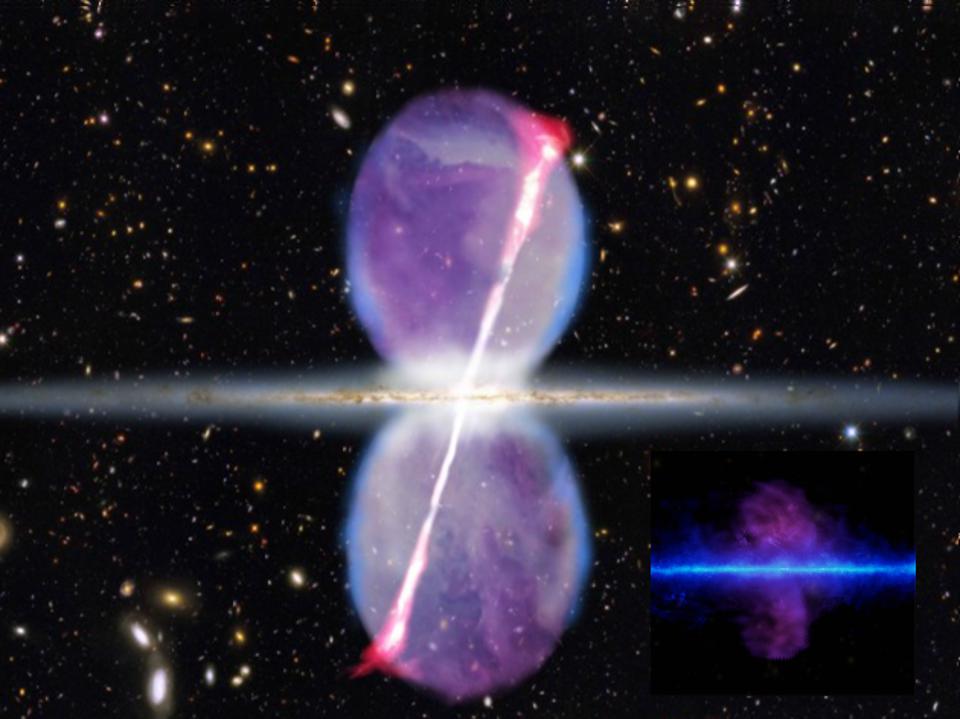

In the main image, our galaxy’s antimatter jets are illustrated, blowing ‘Fermi bubbles’ in the halo of gas surrounding our galaxy. In the small, inset image, actual Fermi data shows the gamma-ray emissions resulting from this process. These “bubbles” arise from the energy produced by electron-positron annihilation: an example of matter and antimatter interacting and being converted into pure energy via E = mc^2. We are certain that no antimatter signature in our galaxy arises from either antimatter stars or large clumps of antimatter.

However, we also expect that there actually must be some new physics out there, because of the overwhelming astrophysical evidence for dark matter. While the true nature of dark matter will remain a mystery until the particle (or at least one of the particles) responsible is detected directly, many dark matter scenarios exist where not only is dark matter its own antiparticle, but that dark matter annihilations will also produce electron-positron pairs. As long as your dark matter particle is massive enough so that electron-positron pairs can be generated from the energy released when dark matter particles annihilate, this type of antimatter ought to be generated under some conditions.

So how do we decide: dark matter or “mundane” physics? Which one is responsible for blowing these “Fermi bubbles” in our galaxy?

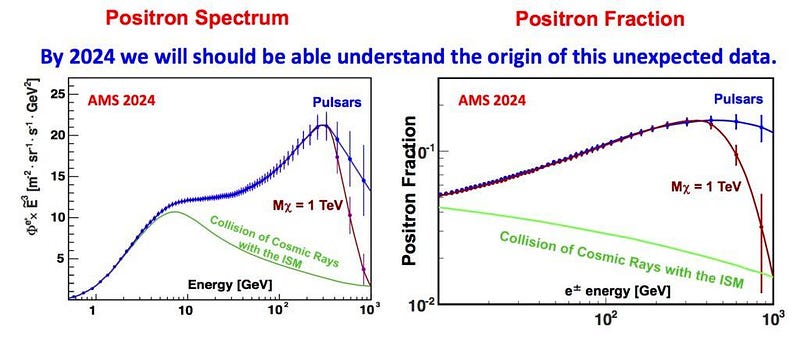

Whenever you have multiple possible physical explanations for what could cause an observable phenomenon, the key to telling which one matches reality is to tease out differences between the explanations. In particular, positrons due to dark matter should experience a cutoff at specific energies (corresponding to the mass of the dark matter particles), while positrons generated by conventional astrophysics should fall off more gradually. In other words, looking at the energy spectrum of these positrons, directly, should tell us what the answer is.

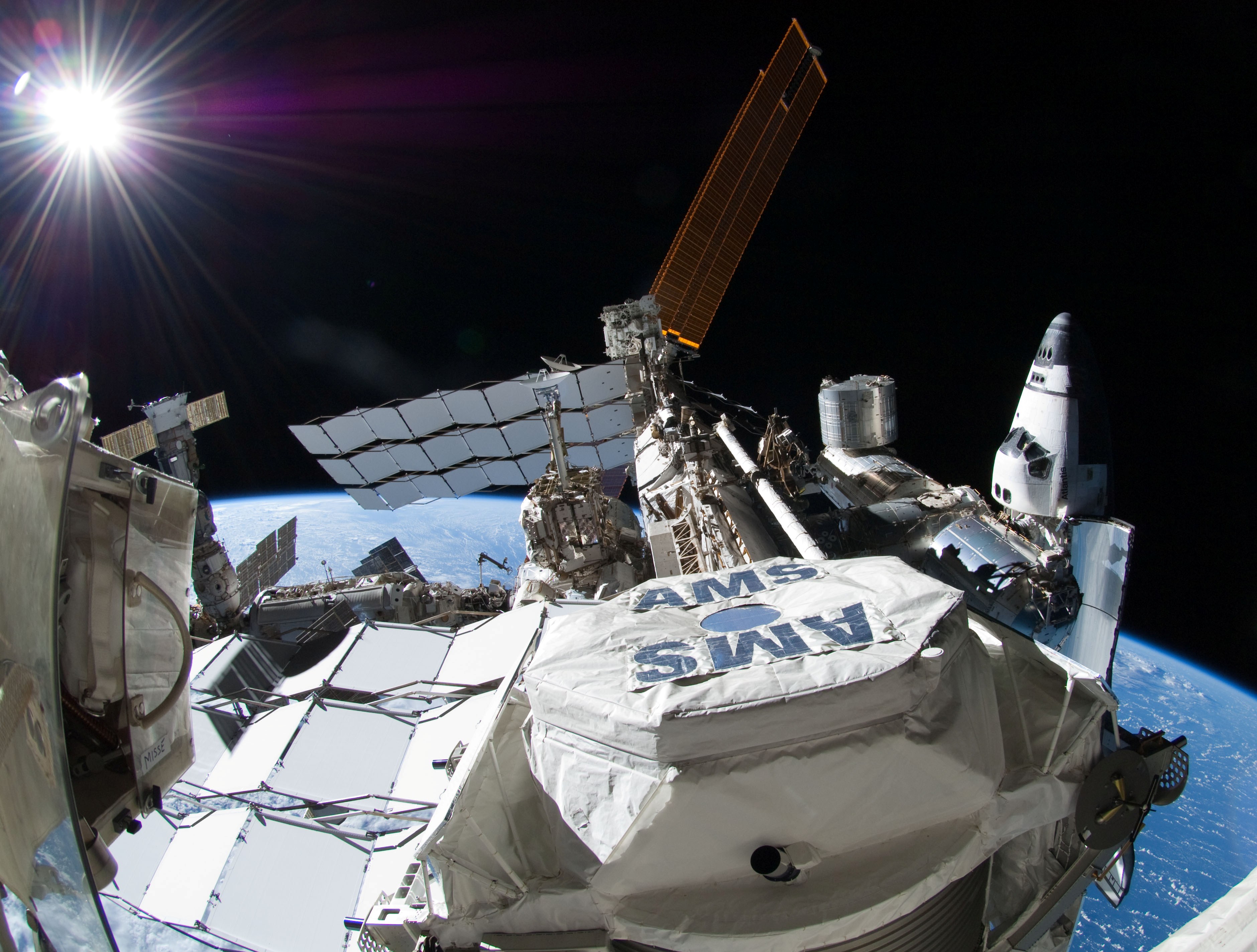

Exterior view of the ISS with the alpha magnetic spectrometer (AMS-02) visible in the foreground. The AMS-02 experiment was installed in 2011 and has provided our best measurements of cosmic rays by type and energy of any experiment to date. It is particularly good at measuring positrons.

In 2011, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer experiment (AMS-02) was launched, with the goal of further investigating this mystery. After arriving at the International Space Station aboard the final mission of the Space Shuttle Endeavor, it was quickly set up and began sending data back to Earth within 3 days. During its operational phase, it collected and measured more than ten billion cosmic ray particles per year. Although only a tiny fraction of them were positrons, that’s okay; because of the different energy, charge, and charge-to-mass ratios of the different particles that impacted it, different species of particle could be separated out.

What’s remarkable about AMS-02 is the “magnetic” part of the experiment: magnetic fields bend charge particles, and while the magnetic force on a moving charged particle depends only on its electric charge and velocity, the amount that a particle “bends by” as it passes through the detector is also dependent on the incoming particle’s mass and momentum. This makes AMS-02 able to sort these cosmic rays both by type and by energy, providing us with an unprecedented set of data to evaluate whether the positrons appeared to be due to dark matter or not. At low energies, the data matched the predictions of cosmic rays colliding with the interstellar medium, but at higher energies, something else was clearly at play.

If the AMS-02 experiment would have experienced zero failures and not required any repairs, it would have collected sufficient data to distinguish between pulsars (blue) or annihilating dark matter (red) as the source of the excess positrons. Either way, collisions of cosmic rays with the interstellar medium can only explain the low-energy signature, with another explanation required for the high-energy signatures.

However, just because you’re seeing more positrons above and beyond what we expect would be caused by collisions of cosmic rays with matter in the interstellar medium doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a slam dunk for dark matter. That’s not true by any means. At higher energies, it’s also possible that pulsars, which accelerate matter particles to incredible energies through a combination of their gravitational and electromagnetic forces, could produce a peaked excess of positrons at high energies.

The only way to truly tell those scenarios apart is t