The unprecedented experiment explores the possibility that space-time somehow emerges from quantum information, even as the work’s interpretation remains disputed.

Introduction

Physicists have purportedly created the first-ever wormhole, a kind of tunnel theorized in 1935 by Albert Einstein and Nathan Rosen that leads from one place to another by passing into an extra dimension of space.

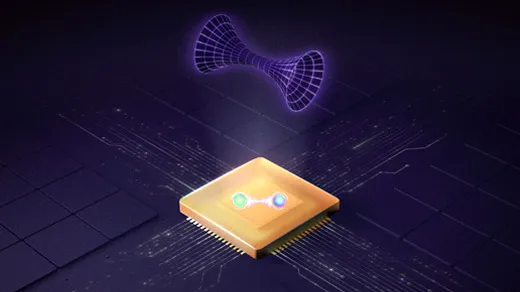

The wormhole emerged like a hologram out of quantum bits of information, or “qubits,” stored in tiny superconducting circuits. By manipulating the qubits, the physicists then sent information through the wormhole, they reported today in the journal Nature.

The team, led by Maria Spiropulu of the California Institute of Technology, implemented the novel “wormhole teleportation protocol” using Google’s quantum computer, a device called Sycamore housed at Google Quantum AI in Santa Barbara, California. With this first-of-its-kind “quantum gravity experiment on a chip,” as Spiropulu described it, she and her team beat a competing group of physicists who aim to do wormhole teleportation with IBM and Quantinuum’s quantum computers.

When Spiropulu saw the key signature indicating that qubits were passing through the wormhole, she said, “I was shaken.”

The experiment can be seen as evidence for the holographic principle, a sweeping hypothesis about how the two pillars of fundamental physics, quantum mechanics and general relativity, fit together. Physicists have strived since the 1930s to reconcile these disjointed theories — one, a rulebook for atoms and subatomic particles, the other, Einstein’s description of how matter and energy warp the space-time fabric, generating gravity. The holographic principle, ascendant since the 1990s, posits a mathematical equivalence or “duality” between the two frameworks. It says the bendy space-time continuum described by general relativity is really a quantum system of particles in disguise. Space-time and gravity emerge from quantum effects much as a 3D hologram projects out of a 2D pattern.

Introduction

Indeed, the new experiment confirms that quantum effects, of the type that we can control in a quantum computer, can give rise to a phenomenon that we expect to see in relativity — a wormhole. The evolving system of qubits in the Sycamore chip “has this really cool alternative description,” said John Preskill, a theoretical physicist at Caltech who was not involved in the experiment. “You can think of the system in a very different language as being gravitational.”

To be clear, unlike an ordinary hologram, the wormhole isn’t something we can see. While it can be considered “a filament of real space-time,” according to co-author Daniel Jafferis of Harvard University, lead developer of the wormhole teleportation protocol, it’s not part of the same reality that we and the Sycamore computer inhabit. The holographic principle says that the two realities — the one with the wormhole and the one with the qubits — are alternate versions of the same physics, but how to conceptualize this kind of duality remains mysterious.

Opinions will differ about the fundamental implications of the result. Crucially, the holographic wormhole in the experiment consists of a different kind of space-time than the space-time of our own universe. It’s debatable whether the experiment furthers the hypothesis that the space-time we inhabit is also holographic, patterned by quantum bits.

“I think it is true that gravity in our universe is emergent from some quantum [bits] in the same way that this little baby one-dimensional wormhole is emergent” from the Sycamore chip, Jafferis said. “Of course we don’t know that for sure. We’re trying to understand it.”

Into the Wormhole

The story of the holographic wormhole traces back to two seemingly unrelated papers published in 1935: one by Einstein and Rosen, known as ER, the other by the two of them and Boris Podolsky, known as EPR. Both the ER and EPR papers were initially judged as marginal works of the great E. That has changed.

In the ER paper, Einstein and his young assistant, Rosen, stumbled upon the possibility of wormholes while attempting to extend general relativity into a unified theory of everything — a description not only of space-time, but of the subatomic particles suspended in it. They had homed in on snags in the space-time fabric that the German physicist-soldier Karl Schwarzschild had found among the folds of general relativity in 1916, mere months after Einstein published the theory. Schwarzschild showed that mass can gravitationally attract itself so much that it becomes infinitely concentrated at a point, curving space-time so sharply there that variables turn infinite and Einstein’s equations malfunction. We now know that these “singularities” exist throughout the universe. They are points we can neither describe nor see, each one hidden at the center of a black hole that gravitationally traps all nearby light. Singularities are where a quantum theory of gravity is most needed.

Albert Einstein, pictured on the top in 1920, and Nathan Rosen, pictured around 1955, stumbled across the possibility of wormholes in a 1935 paper.

The Scientific Monthly (top); AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection

Albert Einstein, pictured on the left in 1920, and Nathan Rosen, pictured around 1955, stumbled across the possibility of wormholes in a 1935 paper.

The Scientific Monthly (left); AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection

Introduction

Einstein and Rosen speculated that Schwarzschild’s math might be a way to plug elementary particles into general relativity. To make the picture work, they snipped the singularity out of his equations, swapping in new variables that replaced the sharp point with an extra-dimensional tube sliding to another part of space-time. Einstein and Rosen argued, wrongly but presciently, that these “bridges” (or wormholes) might represent particles.

Ironically, in striving to link wormholes and particles, the duo did not consider the strange particle phenomenon they had identified two months earlier with Podolsky, in the EPR paper: quantum entanglement.

Entanglement arises when two particles interact. According to quantum rules, particles can have multiple possible states at once. This means an interaction between particles has multiple possible outcomes, depending on which state each particle is in to begin with. Always, though, their resulting states will be linked — how particle A ends up depends on how particle B turns out. After such an interaction, the particles have a shared formula that specifies the various combined states they might be in.

The shocking consequence, which caused the EPR authors to doubt quantum theory, is “spooky action at a distance,” as Einstein put it: Measuring particle A (which picks out one reality from among its possibilities) instantly decides the corresponding state of B, no matter how far away B is.

Entanglement has shot up in perceived importance since physicists discovered in the 1990s that it allows new kinds of computations. Entangling two qubits — quantum objects like particles that exist in two possible states, 0 and 1 — yields four possible states with different likelihoods (0 and 0, 0 and 1, 1 and 0, and 1 and 1). Three qubits make eight simultaneous possibilities, and so on; the power of a “quantum computer” grows exponentially with each additional entangled qubit. Cleverly orchestrate the entanglement, and you can cancel out all combinations of 0s and 1s except the sequence that gives the answer to a calculation. Prototype quantum computers made of a few dozen qubits have materialized in the last couple of years, led by Google’s 54-qubit Sycamore machine.

Meanwhile, quantum gravity researchers have