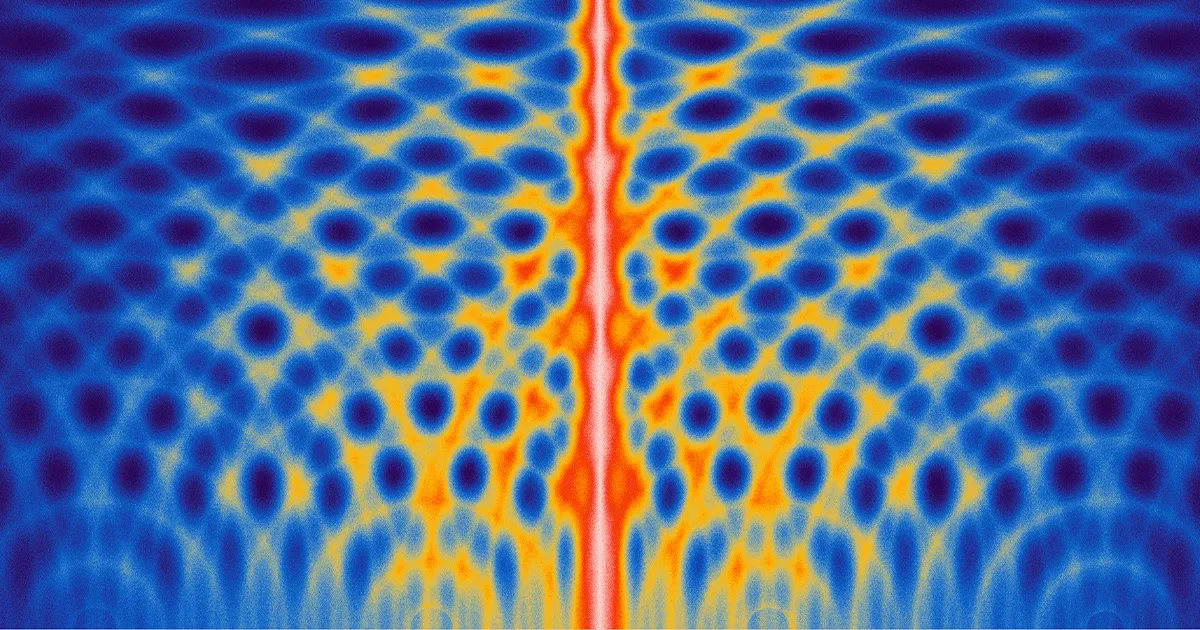

The interference pattern is a supremely strange result because it implies that both of the particle’s possible paths through the barrier have a physical reality.

The path integral assumes this is how particles behave even when there are no barriers or slits around. First, imagine cutting a third slit in the barrier. The interference pattern on the far wall will shift to reflect the new possible route. Now keep cutting slits until the barrier is nothing but slits. Finally, fill in the rest of space with all-slit “barriers.” A particle fired into this space takes, in some sense, all routes through all slits to the far wall — even bizarre routes with looping detours. And somehow, when summed correctly, all those options add up to what you’d expect if there are no barriers: a single bright spot on the far wall.

It’s a radical view of quantum behavior that many physicists take seriously. “I consider it completely real,” said Richard MacKenzie, a physicist at the University of Montreal.

But how can an infinite number of curving paths add up to a single straight line? Feynman’s scheme, roughly speaking, is to take each path, calculate its action (the time and energy required to traverse the path), and from that get a number called an amplitude, which tells you how likely a particle is to travel that path. Then you sum up all the amplitudes to get the total amplitude for a particle going from here to there — an integral of all paths.

Naïvely, swerving paths look just as likely as straight ones, because the amplitude for any individual path has the same size. Crucially, though, amplitudes are complex numbers. While real numbers