If you want to be a decent person, you should care about how you treat other people. What else is important in life? It’s right and fit that we discuss how we can treat each other better. Our chat can’t be limited to not punching your little sister or not eating your roommate’s leftover Pad Thai. Most of the time we treat other people kindly or cruelly by talking — talking to them or about them. If we want to be better people, we should think about how we talk to and about other people — including when we’re mad at them. It’s easy to be nice to someone when you’re happy with them. It’s harder to be kind when dealing with our enemies, strangers, and the least of us. So it’s legitimate to examine how we respond to speech that makes us mad. We should have a thoughtful conversation about whether modern American culture encourages us to react excessively and even cruelly to speech we don’t like, how that impacts people, and what we should do about it.

The New York Times’ Editorial Board did not offer such a thoughtful conversation in its piece “America Has a Free Speech Problem,” which discusses oft-invoked “cancel culture.” It’s vexingly unserious.

The problems begin in the lede, which the Editorial Board used on social media to promote the piece:

For all the tolerance and enlightenment that modern society claims, Americans are losing hold of a fundamental right as citizens of a free country: the right to speak their minds and voice their opinions in public without fear of being shamed or shunned.

This is sheer nonsense from the jump. Americans don’t have, and have never had, any right to be free of shaming or shunning. The First Amendment protects our right to speak free of government interference. It does not protect us from other people saying mean things in response to our speech. The very notion is completely incoherent. Someone else shaming me is their free speech, and someone else shunning me is their free association, both protected by the First Amendment.

Many words later in the piece, the Editorial Board ambiguously acknowledges this, sort of:

It is worth noting here the important distinction between what the First Amendment protects (freedom from government restrictions on expression) and the popular conception of free speech (the affirmative right to speak your mind in public, on which the law is silent). The world is witnessing, in Vladimir Putin’s Russia, the strangling of free speech through government censorship and imprisonment. That is not the kind of threat to freedom of expression that Americans face. Yet something has been lost; the poll clearly shows a dissatisfaction with free speech as it is experienced and understood by Americans today.

I appreciate the Board correcting its opening mistake 3/4ths of the way through the op-ed, but it’s still incoherent. “[T]he popular conception of free speech [the affirmative right to speak your mind in public, on which the law is silent]” is vague and nonsensical too. The law isn’t silent on the affirmative right to speak your mind in public. The law protects it. And this articulation of the “popular conception” still doesn’t even attempt to explain where your conceived right to speak ends and my conceived right to respond begins.

Some defenders of the op-ed say that critics are being too pedantic, and that it’s clear the Times is talking about norms, or “free speech values,” or “free speech culture” or “norms.” First, bullshit. It’s the New York Times Editorial Board. I’m not critiquing a middle-schooler’s essay. I can hold them to a standard of coherence. More importantly, slapping a different label like “norms” on the assertion doesn’t cure the central problems it poses. The problems are these:

-

We don’t have anything resembling a consensus on what “cancel culture” is and we’re not having a serious discussion about defining it;

-

We don’t have a consensus on how we reconcile the interests of speakers and responders, and we’re not making a serious attempt to reach one.

-

We don’t have a consensus about what to do about it and we’re not trying to reach one.

Ignoring these problems isn’t a quibble. They’re the main event.

The Editorial Board does not attempt to define “cancel culture” or articulate the boundaries of the sort of shaming, shunning speech that should concern us. You can’t blame them. Hardly anyone tries. Even the famous Harper’s Letter — praised as an attempt to start a dialogue about the subject — criticized speech that tries to punish or silence, but didn’t try to define it. The Times simply waves an imperious hand at the issue:

However you define cancel culture, Americans know it exists and feel its burden.

That’s nice, I’m sure, but it’s not actionable, any more than the Harper’s Letter was. Both pieces make references to some things we might try to agree on — like people getting fired for speech — but neither offers even a gesture at getting there.

Some thoughtful people of good faith have tried — I’d cite Greg Lukianoff and Nicholas Christakis, for instance. I’m going to offer a working definition for the purposes of this essay: “cancel culture” is when speech is met with a response that, in my opinion, is very disproportionate. Perhaps that sounds cynical, and I could certainly give you a Justice-Breyer-seven-factor balancing test, but that’s what this discussion boils down to: just as we constantly debate norms of what speech is socially acceptable, we debate norms about what responses to speech are socially acceptable.

Let’s discuss some examples, because when I criticize sloppy use of “cancel culture” I’m accused of denying that there are ever any unfair, disproportionate, or evil responses to speech. I don’t deny that. What happened to Justine Sacco was, in my opinion, very disproportionate. What happened to David Shor was disproportionate and maddeningly stupid. What’s happening in the community of Young Adult Fiction seems like a complete shitshow that makes me want to avoid everyone there. What happened to Professor Greg Patton was disproportionate and anti-Asian bigotry to boot. Shouting invited speakers down so they can’t speak and attendees can’t listen is fascist and contemptible. I could go on, but you get the point.

Why should we care about having a serious discussion about defining cancel culture? We should because simply complaining about it in the abstract, without attempts to define it, without actionable responses, and without taking the rights of “cancellers” doesn’t ease the culture war. It inflames it.

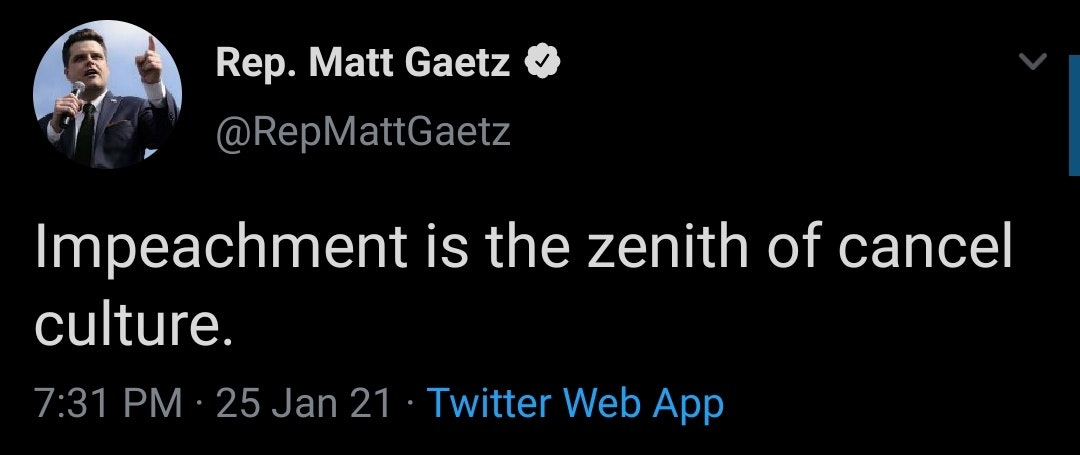

There are several problems. One is that “cancel culture” is relentlessly, constantly used in a cynical, bad-faith way. Vladimir Putin claims that the West is trying to “cancel” Russia merely for invading a sovereign nation — a suggestion echoed, I sure hope ironically, in the Times itself. Mike Lindell, who indulged in