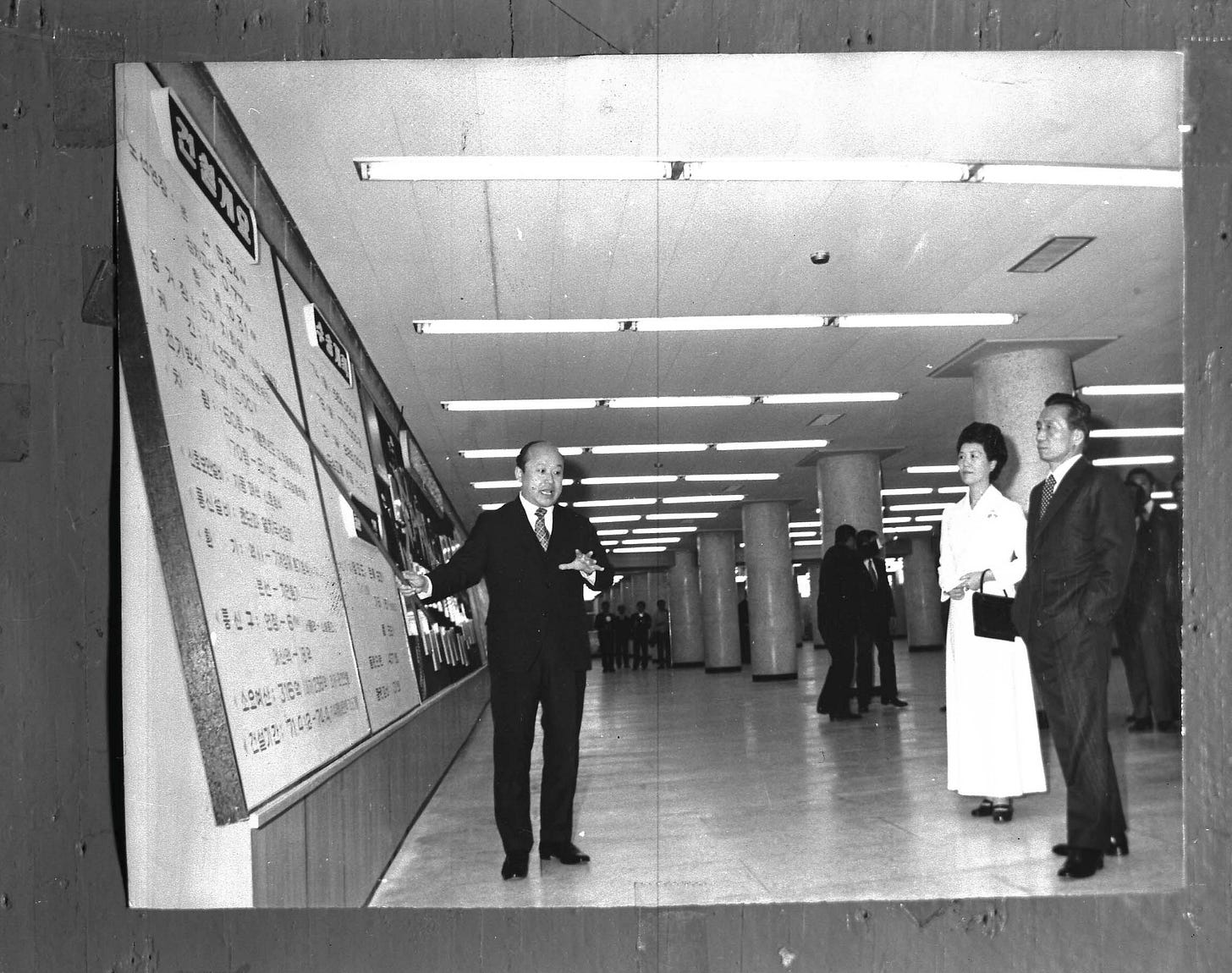

It is past 11 a.m. in Seoul on August 15, 1974, the 29th birthday of the Republic of Korea. The mood on the platform at Cheongnyangni Station is tense and sombre. Cameramen and journalists have fled the station already. After confusion and a previous cancellation, the ribbon is brought back out to be cut. The Mayor of Seoul and three government officials are rushed out to line up and cut the ribbon. None of the men smile for the cameras.

And so, under the most awkward, funereal atmosphere, Seoul opened South Korea’s first-ever subway line. It is hard to imagine a more uncertain and confusing beginning to one of the most celebrated urban mass transit networks in the world — now expanded to nine Metro lines, several more commuter lines, and a national high-speed rail network centralized around the capital city. But perhaps such dispositions were an appropriate mood for the event: Line 1 would grow beyond the original planners’ wildest expectations and its unconstrained growth will reshape not only Seoul’s mass transit but Seoul and the country themselves. The history leading to Line 1’s creation is also marked by volatility and violence — quite neatly in line with that of the Korean peninsula in the 20th century.

Why were the men who cut the ribbon so sad?

1899 was the birthyear for rail in the Korean peninsula, with the advent of two separate railways connecting Seoul — then called Gyeongseong, the capital city of the Joseon Dynasty — in two different directions. First was the Gyeongin Railway which connected Gyeongseong to the port city of Incheon to its west in September. (Note the portmanteau “Gyeong” “In”, a common wordplay in Korean) Under the American entrepreneur James R. Morse, the Gyeongin Railway connected Incheon’s port district of Jemulpo to Noryangjin, a port on the south bank of the Han River. A year later, the Gyeongin Railway crossed the Han River and terminated at the current Seoul Station north of the river.

Second was the opening of Gyeongseong’s first tram line in May 1899. Also built by Americans Henry Collbran and Harry Bostwick, the line started right outside Daehan Gate at Deoksu Palace, where King Gojong resided. The line travelled north up Sejongro, turned right on Jongro and travelled east past Dongdaemun (East Gate) to terminated next to rice fields of Cheongnyangni. The last leg to Cheongnyangni was more for symbolism than logistics; Cheongnyangni was where the tomb of Gojong’s wife, Queen Min, was buried after she was murdered by Japanese assassins in Gyeongbok Palace in 1895. As much as urban connectivity as priority, this first tram line was built as a reminder of a recent historical injustice and a play at the king’s own heartstrings by extending a literal train line from his palatial footsteps directly to his slain wife’s tomb. Despite the emotional charge at patriotism, locals near the tram line rioted against it, seeing it as a foreign intrusion on the local feng shui and threat to their properties.

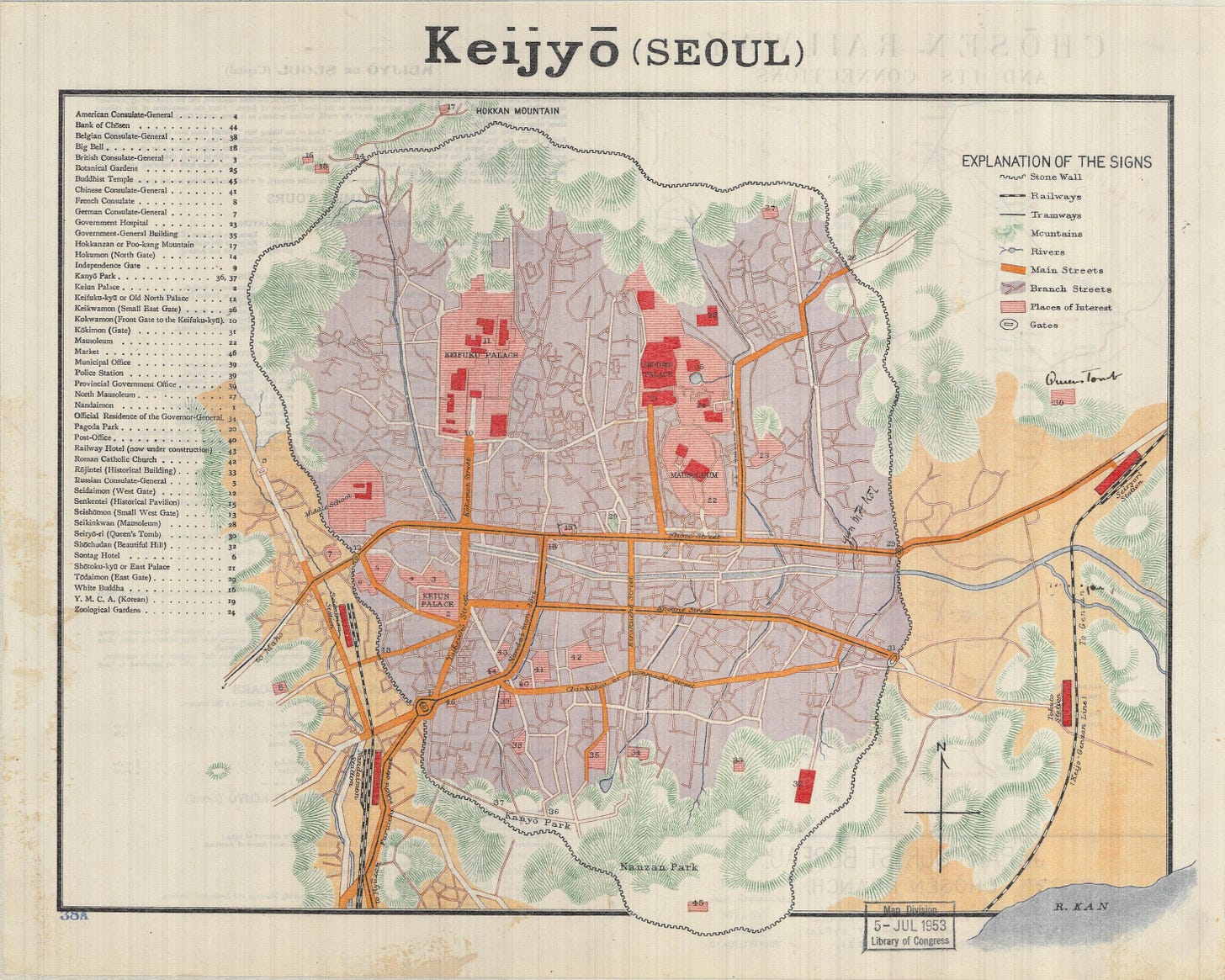

Once Japan annexed Korea in 1910 and abolished the 505-year-old Joseon Dynasty, rail played a crucial role in the Japanese colonial management of economic growth and resource extraction. Gyeongseong, now called Keijo under Japanese rule, became the epicenter of a national rail network which connected the southern port cities of Busan, Mokpo, Gunsan, and Incheon to the industrial northern cities of Pyeongyang, Wonsan, and Sinuiju, the last of which extended into Manchuria. Under Japanese rule, Keijo’s tram network expanded as its new centers around Japanese-populous neighborhoods in the southern half of Keijo, around what is now Euljiro (then called Kogane-cho) and Toegyero (then called Honmachi). Yongsan Station, outside the city walls and located next to the Japanese Army Headquarters south of Seoul Station, emerged as a new railway hub for colonial affairs. Japanese soldiers, Korean forced labor, rice, and other materiel departed from or passed through Yongsan Station as Japan’s wartime efforts grew in the 1930s and 1940s until Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945.

The Korean War between June 1950 and July 1953 had a devastating impact on Seoul’s railways. All bridges crossing the Han River were destroyed and railway tracks and depots were targeted by aerial bombings on both sides; for example, a recent declassified CIA record confirmed the US Air Force targeted Yongsan Station and nearby Haebangchon neighborhood — then packed with refugees fleeing the north — repeatedly with B-29 bombers in September 1950, resulting in total devastation of rail infrastructure around Yongsan and the refugee camps at Haebangchon, resulting in thousands of civilians dead. For the Seoul tram network, the war crippled their operations beyond full repair: nearly one-ninth of its trackage and nearly half of its streetcars were rendered unusable, and countless catenaries and equipment were looted by desperate civilians.

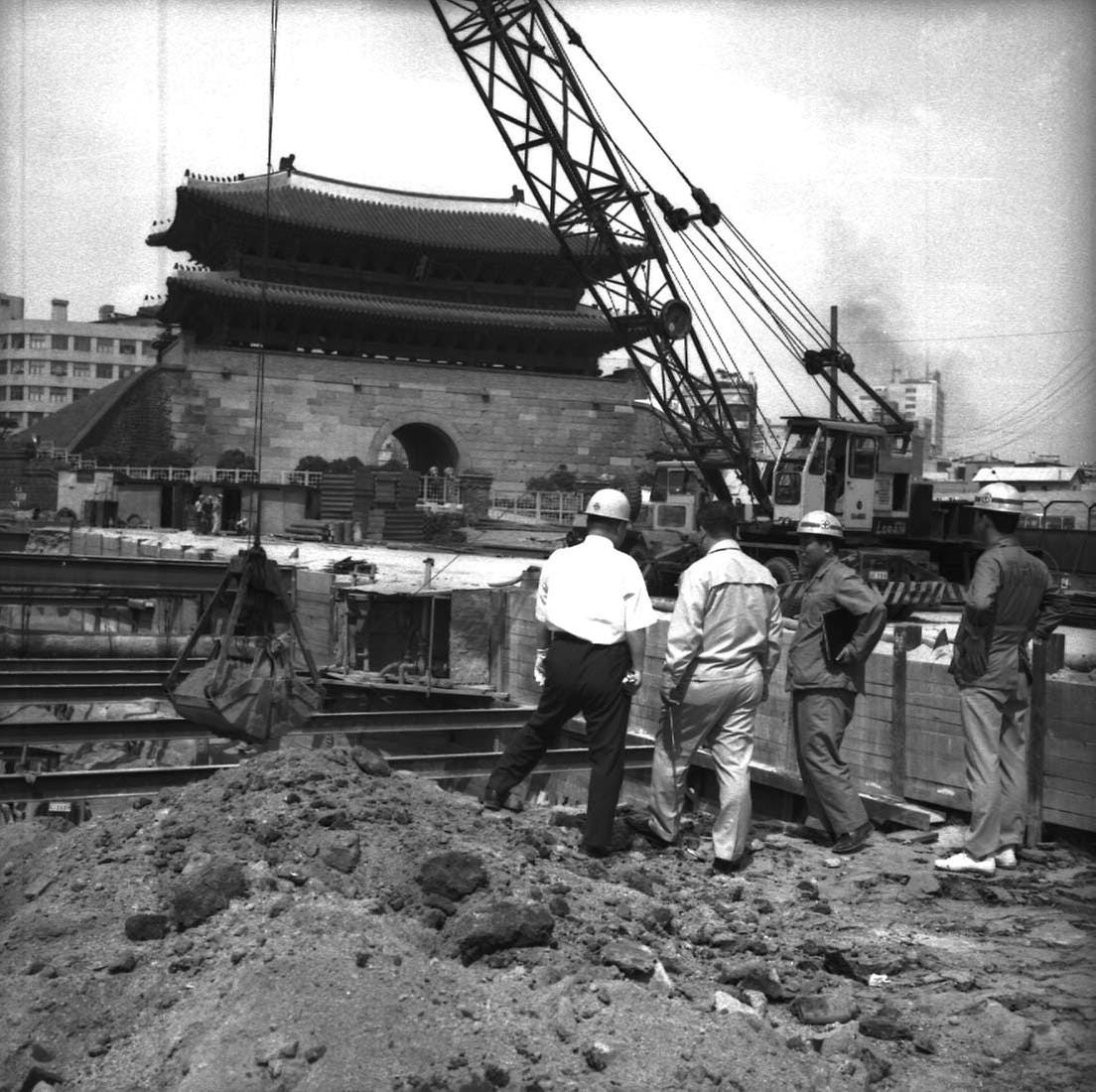

Despite restarting service in 1952 and entering peacetime following the Korean War’s armistice in 1953, the Seoul tram network struggled due to its wartime damages. In the 1950s, Seoul received nearly 60 trams from the United States to shore its depleted rolling stock: nearly 20 from the Atlanta streetcar system, discontinued in 1949, and nearly 40 from the Pacific Electric Railway Company in Los Angeles, which too was on its decline. However, the Seoul tram network continued to decline under aging infrastructure and growing deficits due to a government-imposed fare freeze. Under a fast-growing Seoul with rising rates of automobile ownership by a small but emergent urban middle class in the 1960s, the Seoul government put the kibosh on the nearly 70-year-old tram network. Concrete was poured over discontinued tram lines across Seoul. The last tram in Seoul ran for service on November 30, 1968.

Video timelapse of the growth and dismantling of the Seoul tram system, with advent of Line 1, between 1899 and 1970

Between 1955 and 1970, the population in the city of Seoul more than tripled from 1.6 million to 5.5 million, as displaced postwar families from both North and South moved in search of industrial jobs. Traffic jams became an increasingly common sight, with trams offering little relief. After 1968, buses and automobiles were the only modes of moving within the city of Seoul. Intercity trains connecting Seoul, Yongsan, and Cheongnangnyi stations to Incheon to the west, Suwon to the south, and Baengmagoji to the north (part of a line to Wonsan in North Korea, now disconnected) ushered in and out commuters to add to Seoul’s crowding issues.

The first discussions of a subway line in Seoul were recorded in 1958, under Rhee Syngman’s presidency, a surprisingly early register for a rebuilding South Korean government looking toward its future. In 1965, Seoul Mayor Kim Hyun-ok unveiled his plans for a four-line Seoul subway system, with Line 1 as an underground tunnel through central Seoul connecting to the intercity lines at Seoul Station in the west and Cheongnangnyi station in the east. As an aggressive and haphazard builder-mayor of a rapidly industrializing metropolis, Kim dreamed of a subway network before he was forced to resign in 1970, after a public apartment built under Kim’s administration collapsed and killed 34 residents.

Kim was succeeded by Yang Taek-sik as Seoul Mayor, a like-minded mayor who built on Kim’s subway dreams. Yang modified Kim’s four-line plan, with the Line 1 tunnel running up north up Sejongro, then a sharp right on Jongro heading east to Cheongnyangni — a near-identical route as the first tram line of heavy symbolism built under King Gojong. Shortly after his promotion on April 1970, Yang made subway construction a key priority and directly inquired President Park Chung-hee to green light the project.

Then Vice Prime Minster and Minister of Economy Kim Hak-ryeol, however, vehemently opposed Yang’s proposal for a Seoul subway. Kim asserted to Park that a subway construction would increase prices, accelerate Seoul’s ongoing population explosion, and unduly test South Korea’s developing economy; in one conversation with Park, Kim warned “if you build this subway, the country will be ruins”. One story believes Kim’s opposition was not economics but personal politics: he was furious at Yang for bypassing him and asking Park directly. Another story goes Park was on the fence about Yang’s request until he met the Japanese Ambassador to South Korea. The ambassador told Park “the subway is a global trend. In the case of Tokyo, citizens cannot live a day without the subway. Therefore you will have to build one.” Park soon gave Yang his blessings to build a four-line subway network, beginning with the Line 1 tunnel between Seoul Station and Cheongnangnyi Station.

In the summer of 1970, Park solicited the help of Japanese expertise to plan and oversee construction and import Li