For the entirety of my adult life, routine psychiatric appointments have been an inconvenient constant. Though I rarely talk about it in detail, I have always been prone to fits of depression and suffer from an anxiety disorder, both of which impact my ability to think or really function at all if left unchecked. I hate these appointments, and I really wish that I didn’t need them in my life. That said, if there is one thing I take solace in, it’s the straightforward, predictable nature of this otherwise annoying necessity. There are almost never surprises, which I’m grateful for. I’m not looking for surprises when I’m talking to a doctor.

But during my most recent check-in, the nurse practitioner I spoke with did just that when she advised that I start “grounding”.

Initially – logically – I assumed that grounding had to be some sort of psychological coping strategy that used the word figuratively. However, it soon became evident that the nurse practitioner was talking about literally grounding. In an electrical sense. Alongside the familiar Wellbutrin/Prozac regimen that’s been prescribed to me for the better part of a decade, I was instructed to spend no less than twenty minutes per day outside, barefoot, in direct contact with the ground. According to her, this would serve as a means of evening out “energy imbalances” I might be experiencing.

My immediate knee-jerk reaction was that a patch of grass, no matter how idyllic, could not possibly have the miraculous healing powers capable of eliminating symptoms I’ve dealt with since approximately the second grade. But the fact that this advice came directly from a medical professional lent some degree of credence. Presumably, the person prescribing this peculiar practice underwent countless clinical hours and years of postgraduate studies. Surely, these experiences would have made her immune to spouting entirely baseless snake oil pitches.

Right???

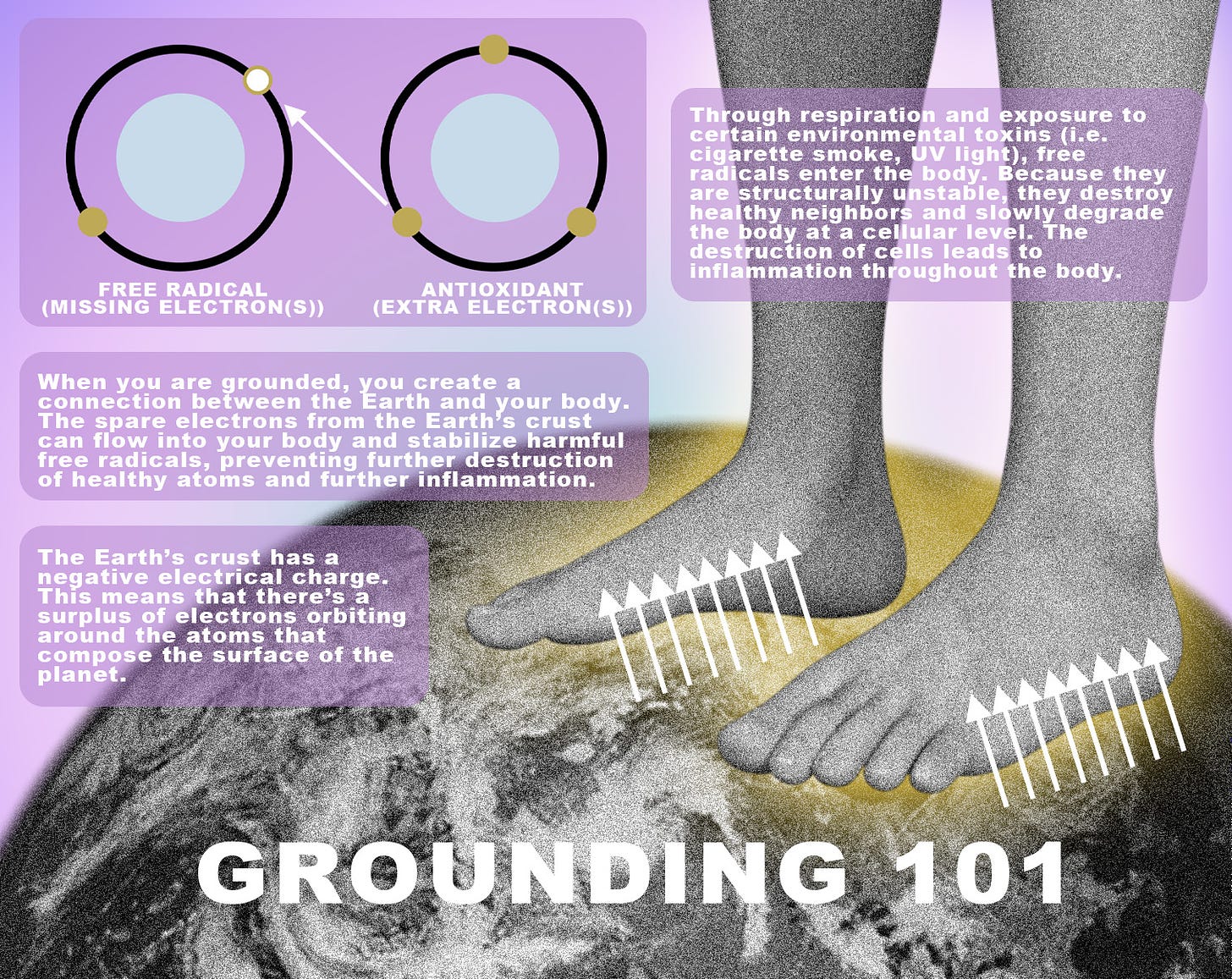

So, I second-guessed my gut reaction and started looking into how exactly grounding (also known as earthing) helps the body. I’m including a footnote with a more detailed description

of grounding theory for those interested, but here’s a rudimentary diagram that more or less covers how it (allegedly) works:

Though not necessarily an inflammatory disease, experts around the world have long suspected links between depression and inflammation (which is probably why it was suggested that I try grounding in the first place). But depression management is only the tip of the iceberg – a growing number of people believe that grounding directly benefits physical as well as mental health. Advocates consistently insist that grounding can, at the very least, improve circulation, speed up immune systems, and even regulate circadian rhythm.

To a certain extent, it’s difficult to argue that the reported positive effects of grounding in nature

are entirely the product of a placebo. Numerous studies connect stress reduction with immunological and cardiovascular health, and a growing body of evidence suggests a correlation between recreational contact with nature and lowered stress levels. It’s entirely possible that spending time barefoot in a green space may indirectly

improve the overall well-being of an individual.

A quick search revealed that my NP is far from the only person hooked on grounding. #Grounding has over 550 million views on TikTok, yields nearly 2 million results on Instagram

, and appears to have vocal, dedicated followers across the social media spectrum. In August 2023, USA Today posted an article that covered growing interest in the practice and offered tips on how to efficiently ground. The Wall Street Journal included brief concessions that admitted the implausibility of it all, only to profess that grounding poses little danger or risk outside of an occasional bee sting.

And perhaps at a surface level, there’s truth to that sentiment. Even so I couldn’t shake the feeling that something corrupt and hideous lurked behind the seemingly harmless call to touch grass.

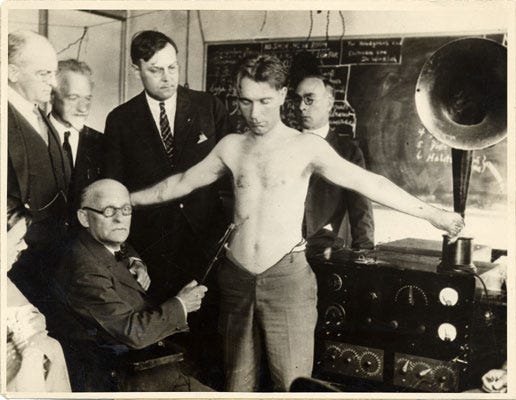

My skepticism toward the idea of electricity-as-cure-all isn’t unfounded. For as long as electricity has been accessible, there have been people fervently advertising its ability to heal.

The idea of medical electricity dates back to at least the 1740s, and a few tinkerers even created unusual apparatuses that surgeons and doctors used in experimental treatments. Though the results of many such experiments were, as one authority wrote, “too uncertain to be worth mentioning,” surviving manuscripts suggest that physicians recognized that the field of medical electricity had the potential to be profitable. However, in those early days of trial and error, electricity was not understood or accessible enough to realistically be employed in healing.

As we all know, things didn’t stay that way for long. The 19th century was a time of rapid electrical innovation, with influential scientists and electrical engineers like Michael Faraday, Thomas Edison, Heinrich Hertz, and Nikola Tesla more or less working in tandem. By the year 1900, the streets of major cities like Paris and New York were lit with streetlamps powered by thermal power stations, and a handful of wealthy homes were outfitted with electrical sockets that fueled the earliest incandescent lightbulbs.

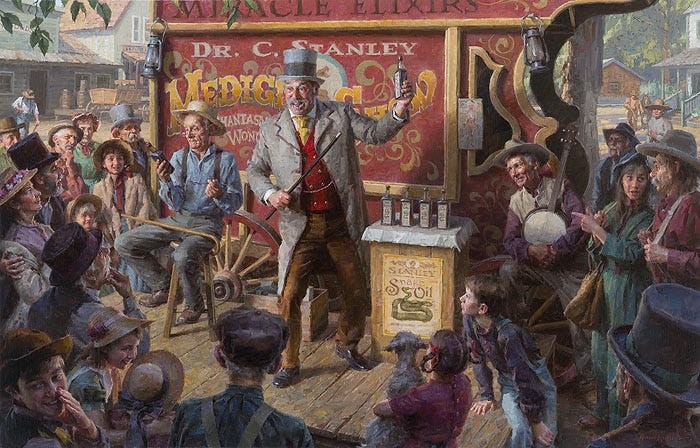

Coincidentally, the 19th century was also an international golden age for medical quackery. Beginning in the late 1700s, there was an explosion of questionable patent medicine coming out of Great Britain. The business of marketing sensational cure-alls quickly spread across the (then expansive) British empire. When the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 soured international trade relations between Britain and the United States, inventive American conmen started brewing medicinal tonics and elixirs of their own. Traveling snake oil salesmen peddled their wares westward, using theatric pitches that praised the therapeutic benefits of whatever they happened to have on hand. By the time unsuspecting customers realized they were swindled into buying sugar pills or salt water, the combination salesman/showman would have already moved on to the next town.

After a century of customers falling victim to blatantly false advertising and accidental poisonings, Europe and the United States finally started passing food and drug legislation regulating medicinal contents around the start of the 20th century. As random home brew remedies became increasingly difficult to sell, some career conmen revisited the idea of electrical healing. Though electricity was becoming an increasingly common fixture in everyday life, the phenomenon was still poorly understood by most people, allowing persuasive merchants to pitch electrotherapy as something quasi-magical. Better yet, electrical healing products bypassed early food and drug regulations

by virtue of electricity not being a food or a drug.

Just three years after the formation of the US Food and Drug Administration in 1906, a physician by the name of Albert Abrams began purporting that he had the ability to diagnose and treat disease through a practice he dubbed radionics (or electromagnetic therapy). Soon after, he promoted an invention called the Dynomizer, which claimed to be able to diagnose any known disease from a single drop of blood

. Once equipped with a diagnosis, Abrams was able to “treat” ailments with a second invention called the Oscilloclast, which professed to treat various conditions by “harmonizing” irregular electronic vibrations occurring at an atomic level.

Abrams’ fantastic claims were fairly easily debunked by the American Medical Association

, and an in-depth exposé and investigation conducted by Scientific American further damaged Abrams’s credibility. But even after being accused of quackery, Abrams retained plenty of believers

. A 1922 issue of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal describes his written claims as “propaganda written up in a sensational way and very cleverly interlarded with a few scientific and many pseudo-scientific facts”. Thousands of practitioners were so convinced of the legitimacy of his claims that they’d lease machines from Abrams for hundreds of dollars per month (though only on the condition that lessees sign a contract agreeing to never pry open or examine the inner wirings of the device in question

).

After Abrams’s death in 1924, a few radionic-adjacent scams came and went. Over the next several decades, a few naturopaths peddled devices that claimed to zap away parasitic infections

or balance bioenergetic forces

. However, for the most part, electricity as a cure-all largely fell out of fashion.

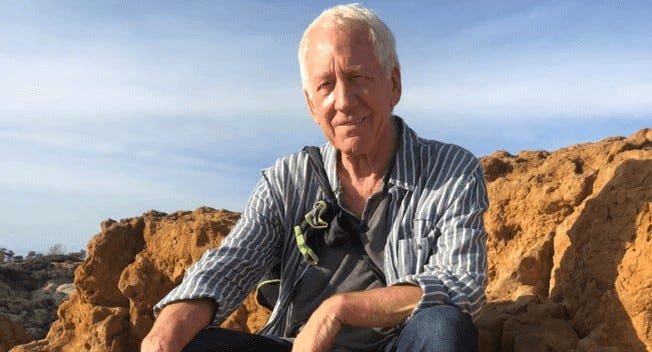

But in the last twenty-five years, a man named Clint Ober has almost singlehandedly revived and remodeled the ideas that Abrams popularized for a modern (but equally exploitable) audience.

Ober has enjoyed a life filled with success. Despite being thrust into the workforce without much in terms of formal education, he somehow managed to pull himself up by the bootstraps so hard that he became the CEO of a cable installation and distribution service before reaching age 30. The Telecrafter Corporation subsequently became the largest company of its kind in the United States during a time of unprecedented cable demand. This success allowed Ober to spearhead a new endeavor in the early 80s called X*PRESS Information Services. Partnered with publisher McGraw-Hill and cable TV magnate TCI, X*PRESS was a subscription-based newsfeed aggregate that transmitted real-time data to personal computers using existing satellite and cable infrastructure

.

Through these business ventures, Clint became rich. So rich, in fact, that he admitted in one interview to having had “a quarter million dollars worth of art hanging in [the] bathroom over the commode”.

But in 1993 (or ‘94 or ‘95 – the details mysteriously vary depending on who exactly Ober is talking to), Clint discovered that he had a life-threatening abscess on his liver. Treated with the best modern Western medicine had to offer, he made a miraculous recovery. Approaching the brink of death, however, sent Ober into an existential tailspin. What’s more, X*PRESS was rendered obsolete by the ever-growing capabilities of the internet. After the product line was discontinued in 1997, Clint reportedly got rid of all of his belongings, bought an RV, and embarked on a soul-searching journey across North America.

While visiting Sedona, Arizona (or in some versions of the story, Key West, Florida), Clint noticed a gaggle of bypassers wearing sneakers with rubber soles and started to think about the repercussions, if any, that came from a life spent disconnected from the Earth. Intrigued by his own idea, he retrofitted his own bed with “metallic duct tape connected by wire to a ground rod” to simulate barefoot contact with the ground. Like magic, the aches and pains that had plagued Clint since his hospitalization significantly diminished.

The authenticity of Clint’s personal anecdote is, of course, impossible to confirm or deny. What we do know is that by the start of 1999, he was the chairman and CEO of a brand new venture – EarthFX Inc.

Since then, Clint has undergone s