Abstract

Lead-formulated aviation gasoline (avgas) is the primary source of lead emissions in the United States today, consumed by over 170,000 piston-engine aircraft (PEA). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that four million people reside within 500m of a PEA-servicing airport. The disposition of avgas around such airports may be an independent source of child lead exposure. We analyze over 14,000 blood lead samples of children (≤5 y of age) residing near one such airport—Reid-Hillview Airport (RHV) in Santa Clara County, California. Across an ensemble of tests, we find that the blood lead levels (BLLs) of sampled children increase in proximity to RHV, are higher among children east and predominantly downwind of the airport, and increase with the volume of PEA traffic and quantities of avgas sold at the airport. The BLLs of airport-proximate children are especially responsive to an increase in PEA traffic, increasing by about 0.72 μg/dL under periods of maximum PEA traffic. We also observe a significant reduction in child BLLs from a series of pandemic-related interventions in Santa Clara County that contracted PEA traffic at the airport. Finally, we find that children’s BLLs increase with measured concentrations of atmospheric lead at the airport. In support of the scientific adjudication of the EPAs recently announced endangerment finding, this in-depth case study indicates that the deposition of avgas significantly elevates the BLLs of at-risk children.

Significance Statement

In the United States, hundreds of millions of gallons of tetraethyl lead-formulated gasoline are consumed by piston-engine aircraft (PEA) annually, resulting in an estimated half-million pounds of lead emitted into the environment. About four million persons reside, and about six hundred K-12th grade schools are located, within 500 meters of PEA-servicing airports. In January 2022, the US Environmental Protection Agency launched a formal evaluation of “whether emissions of lead from PEA cause or contribute to air pollution that endangers public health or welfare.” In support of the EPA’s draft endangerment finding and request of public comment, an ensemble of evidence is presented indicating that the deposition of leaded aviation gasoline significantly elevates the blood lead levels of at-risk children.

Introduction

Over the last four decades, the blood lead levels (BLLs) of children in the United States declined significantly, coincident with a series of policies that removed lead from paint, plumbing, food cans, and automotive gasoline. Most effective among these interventions was the phase-out of tetraethyl lead (TEL) from automotive gasoline under provisions of the Clean Air Act of 1970 and amendments in 1990.

While TEL is no longer used as an additive in automotive gasoline, it remains a constituent in aviation gasoline (avgas) used by an estimated 170,000 piston-engine aircraft (PEA) nationwide. TEL is one of the best-known additives for mitigating the risk of engine knocking or detonation, which can lead to sudden engine failure. In the United States, hundreds of millions of gallons of TEL-formulated gasoline are consumed by PEA annually, resulting in an estimated half-million pounds of lead emitted into the environment. Today, the use of lead-formulated avgas accounts for about half to two thirds of current lead emissions in the United States (1). In a recently published consensus study on options for reducing lead emissions by PEA by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, the authors note: “While the elimination of lead pollution has been a U.S. public policy goal for decades, the GA [General Aviation] sector continues to be a major source of lead emissions” (2).

Several studies have linked avgas use to elevated atmospheric lead levels in the vicinity of airports (3–8). The U.S. EPA estimates that four million persons reside, and about six hundred K-12th grade schools are located within 500 meters of PEA-servicing airports (9). Two studies have statistically linked avgas use to BLLs of children residing in the vicinity of general aviation airports. In their groundbreaking study, Miranda et al (10) reported a striking relationship between child BLLs and airport proximity, noting that “[t]he estimated effect on BLLs exhibited a monotonically decreasing dose-response pattern” with children at 500 and 1,000 meters of an airport at greatest risk of elevated BLLs. In a study involving over 1 million children and 448 airports in Michigan, Zahran et al (11) found that child BLLs: (1) increased dose-responsively in proximity to airports; (2) declined measurably among children sampled in the months after the tragic events of 9-11, resulting from an exogenous reduction in PEA traffic; (3) increased dose-responsively in the flow of PEA traffic across a subset of airports; and (4) increased in the percent of prevailing wind days drifting in the direction of a child’s residence.

On the basis of such studies and decades of research on the harm to human health caused by lead, various public interest organizations have petitioned the EPA to make an endangerment finding under Section 231 of the Clean Air Act for aviation gasoline (avgas) emissions. While the EPA recognizes that there is no known safe level of lead exposure, it has cautioned that additional scientific research is needed “to differentiate aircraft lead emissions from other sources of ambient air lead” (12) that may cause elevated BLLs in nearby children.

Subsequent to a report prepared for the County of Santa Clara showing that exposure to leaded avgas contributes to child BLLs (13), and a new petition by various nonprofit and governmental organizations, in January 2022 the EPA launched a formal evaluation of “whether emissions of lead from PEA cause or contribute to air pollution that endangers public health or welfare.” In recent weeks, the EPA published its draft endangerment finding and is currently accepting public comment. In this paper, we present relevant information for the scientific adjudication of the EPA’s draft endangerment finding, supporting the conclusion that emissions from PEA independently contribute to child BLLs, potentially endangering the health and welfare of populations residing near over 21,000 general aviation airports that service avgas-consuming aircraft.

Our paper analyzes the BLLs of children (≤5 y of age) over a 10-y observation period (from 2011 January 31 to 2020 December 31) who reside near one PEA-servcing airport–Reid-Hillview Airport (RHV) in Santa Clara County. Of the more than 21,000 airports appearing in the 2017 EPA National Emissions Inventory, RHV ranks 36th in terms of the quantity of emissions released. From 2011 January to 2018 December , 2.3 million gallons of avgas were sold at RHV. At about 2 grams of lead per gallon, and based on an EPA estimate that 95% of lead consumed is emitted in exhaust, over this 8-y period about five metric tons of lead was emitted at RHV.

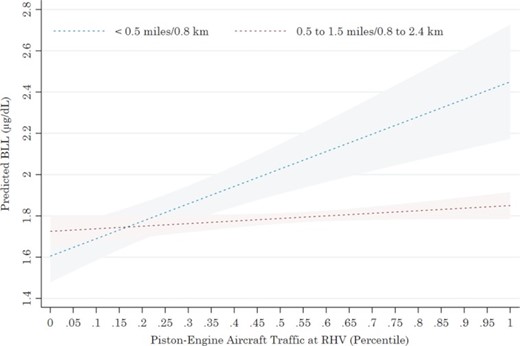

The purpose of our analysis is to test key indicators of exposure risk, including child residential distance, residential near angle (or downwind residence), and volume of traffic from the date of the blood draw. We follow with extended analyses involving the statistical interaction of residential distance and air traffic, a natural experiment exploiting an observed contraction in PEA traffic at RHV following pandemic-related social distancing measures enacted countywide, and an analysis linking child BLLs to atmospheric lead measurements at the airport. Across all tests, we find consistent evidence that exposure to avgas increases child BLLs, adding a data-rich and in-depth case study to the nascent scientific literature on the epidemiological hazard of leaded avgas.

Results

Main analysis

We begin with analysis of our three main indicators of avgas exposure risk: (1) child residential distance, (2) child residential near angle, and (3) child exposure to PEA traffic. Table 1 reports regression coefficients on our main indicators of exposure risk. Our response variable of child BLL is measured in μg/dL units. Following others (10,11), residential distance is also divided into intervals: <0.5 miles (or <0.8 km), 0.5 to 1 mile (or 0.8 to 1.6 km), and 1 to 1.5 miles (or 1.6 to 2.4 km) from RHV (Our inner orbit of exposure risk at < 0.5 miles conforms to previous research. Miranda et al (10) find that children at 500m to 1km from a general aviation airport in North Carolina are at highest at-risk of presenting with elevated BLLs. Zahran et al (11) find that sampled children within 1km of 448 airports in Michigan are at greatest risk. The EPA (14