Years before she was even sure the James Webb Space Telescope would successfully launch, Christina Eilers started planning a conference for astronomers specializing in the early universe. She knew that if — preferably, when — JWST started making observations, she and her colleagues would have a lot to talk about. Like a time machine, the telescope could see farther away and farther into the past than any previous instrument.

Fortunately for Eilers (and the rest of the astronomical community), her planning was not for naught: JWST launched and deployed without a hitch, then started scrutinizing the early universe in earnest from its perch in space a million miles away.

In mid-June, about 150 astronomers gathered at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for Eilers’ JWST “First Light” conference. Not quite a year had passed since JWST started sending images back to Earth. And just as Eilers had anticipated, the telescope was already reshaping astronomers’ understanding of the cosmos’s first billion years.

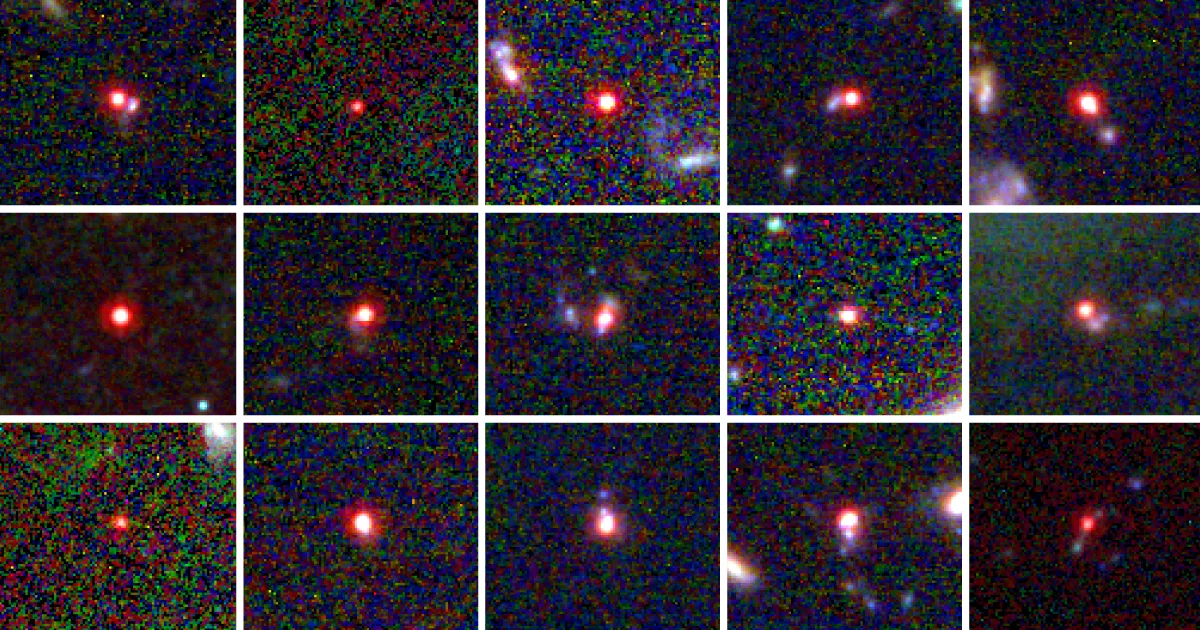

One set of enigmatic objects stood out in the myriad presentations. Some astronomers called them “hidden little monsters.” To others, they were “little red dots.” But whatever their name, the data was clear: When JWST stares at young galaxies — which appear as mere red specks in the darkness — it sees a surprising number with cyclones churning in their centers.

“There seems to be an abundant population of sources we didn’t know about,” said Eilers, an astronomer at MIT, “which we didn’t anticipate finding at all.”

In recent months, a torrent of observations of the cosmic smudges has delighted and confounded astronomers.

“Everybody is talking about these little red dots,” said Xiaohui Fan, a researcher at the University of Arizona who has spent his career searching for distant objects in the early universe.

The most straightforward explanation for the tornado-hearted galaxies is that large black holes weighing millions of suns are whipping the gas clouds into a frenzy. That finding is both expected and perplexing. It is expected because JWST was built, in part, to find the ancient objects. They are the ancestors of billion-sun behemoth black holes that seem to appear in the cosmic record inexplicably early. By studying these precursor black holes, such as three record-setting youngsters discovered this year, scientists hope to learn where the first humongous black holes came from and perhaps identify which of two competing theories better describes their formation: Did they grow extremely rapidly, or were they simply born big? Yet the observations are also perplexing because few astronomers expected JWST to find so many young, hungry black holes — and surveys are turning them up by the dozen. In the process of attempting to solve the former mystery, astronomers have uncovered a throng of bulky black holes that may rewrite established theories of stars, galaxies and more.

“As a theorist, I have to build a universe,” said Marta Volonteri, an astrophysicist specializing in black holes at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics. Volonteri and her colleagues are now contending with the influx of giant black holes in the early cosmos. “If they are [real], they completely change the picture.”

A Cosmic Time Machine

Th