I have been in love with quantum theory since before I started my Ph.D. in the subject over 30 years ago. Suddenly, however, I feel like we should maybe take a break.

The trigger for this quantum of doubt was a new paper. There’s nothing particularly special about it; it’s just a proposal for an experiment that might tell us something more about how the universe works. But, to me, it felt like the final straw. It has opened my eyes to the possibility that, without radical change, quantum physics may forever let me down.

Essentially, I just want to know what I am made of. One hundred years ago this year, the Danish physicist Niels Bohr received the Nobel prize “for his services in the investigation of the structure of atoms.” But I’m still waiting for a straight answer as to what the structure of the atoms that make up my body is. Quantum theory seems to promise an answer that it can’t deliver, at least not in any way that I can comprehend. As Bohr once put it, “When it comes to atoms, language can be used only as in poetry.”

We cover our ignorance with made-up stories known as “interpretations.”

Bohr is often fêted as the founding father of quantum theory and was one of the champions of its oddness. It’s true that quantum is both mysterious and attractive—as enigmatic as the Mona Lisa’s smile. However, there seems to be something troubling about the quantum grin. Whether probing it through theory or through experiment, we quickly arrive at an impasse: We can’t use any of the results to tell us what stuff actually is.

The trouble starts with the workhorse of quantum theory: Erwin Schrödinger’s famous wave equation. It assumes that all quantum stuff can be mathematically modeled as if it were a wave. Schrödinger’s equation is a huge success: It allows us to predict, for instance, exactly what colors of light an atom will emit when stimulated with electromagnetic energy.

However, the beautiful utility of this equation, which is put to work by physicists every day around the world, masks its enigmatic silence about the actual nature of the atoms whose behavior it so successfully describes. While Einstein won a Nobel Prize for proving that light is composed of particles that we call photons, Schrödinger’s equation characterizes light and indeed everything else as wave-like radiation. Can light and matter be both particle and wave? Or neither? We don’t know.

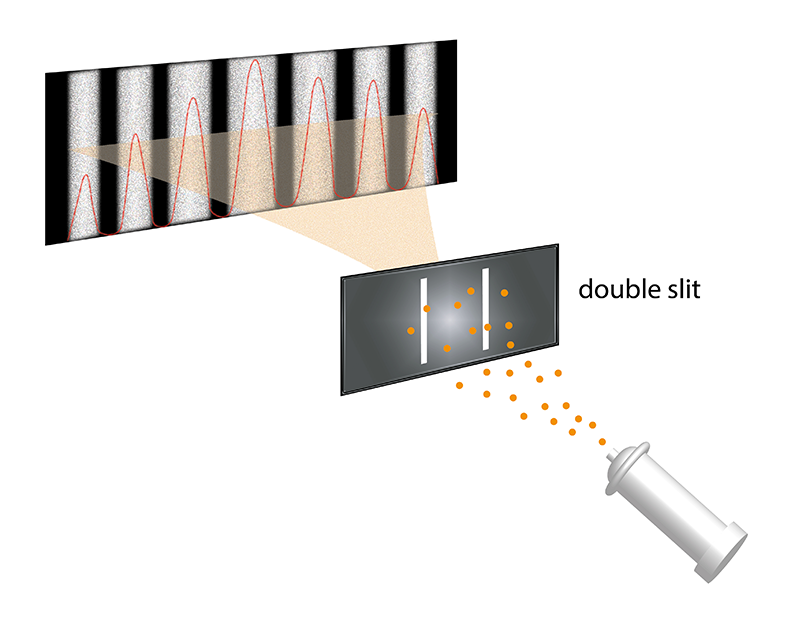

We cover our ignorance with made-up stories known as “interpretations.” There is one classic laboratory setup that inspires most of these stories. Known as the double-slit experiment, it involves a single quantum object being fired toward a pair of openings whose physical dimensions are tailored to the mass and velocity (combined as momentum) of the object. At the far end of the experiment is a detector that records the original object’s final location.

We tend to interpret this experiment through the lens of Schrödinger’s wave equation. To speak of an “object” that we “fire” is to picture it as a particle. But we ascribe it a wave-like character to explain the ensuing observations. So we say that a quantum object can pass through both slits simultaneously, just as a water wave would. The object then emerges from the slits as two separate waves. As these travel on toward the detector, they meet each other, creating a pattern that is characteristic of interacting waves.

This “interference pattern” is a comb-like pattern of alternating high and low density of electron impacts as you look from left to right across the detector. Waves—water waves, for example—produce interference patterns. And so, we reason, there is definitely something wave-like about the quantum object.

However, the interference pattern does not appear at the detector straight away. The single quantum object manifests in the detector as a single particle at a single location. We then repeat the process, and the next object manifests at a different location on the detector. After a million detections, say, we see a clear interference pattern.

The Nobel Prize-winnin