Iceland is a place to see natural wonders: mountains, glaciers, craters, and coastlines. With my love of historical sites, though, there were a few human-built things that I also wanted to see. In particular, I was curious about what Icelandic turf houses look like inside.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links. That means that if you click on one of the links and make a purchase, I will get a small percentage of what you spend. This will not affect your price.

Building with turf

The first settlers in Iceland were Vikings and the occasional Irish monk. They had timber they could use for building: about 30% of Iceland’s land area was birch woods, according to Wikipedia. That didn’t last long, though. They eventually cleared almost all trees from Iceland, either for building materials or firewood or to clear land for farming.

Instead, turf became a commonly used material right through from the Middle Ages until just the last century.

They cut thick pieces of the earth, grass and roots and all, from the ground and used the pieces as bricks to build walls. The base of each wall is stone, then the turf is stacked like bricks on top of that, or in a herringbone pattern. These walls are thick: perhaps a meter or more, and offer good insulation. Wood beams hold up the roof, which is also turf. On the outside, the roof grows grass.

The wooden beams, by the way, as well as the gables that are also made of wood, were, historically speaking, mostly driftwood, a lot of which lands in Iceland. I’m sure that has something to do with ocean currents, but we certainly saw a lot of driftwood on the coastline as we drove around Iceland.

Organic structures

Because it is made of turf, an older Icelandic turf house looks almost as if it’s part of the landscape, if you see it from a distance: just a series of low bumps. The more recent ones, with wooden gables on the front, look like a row of houses.

These were organic structures in that they changed and adjusted over the centuries depending on what the residents needed. The owners could add rooms or remove them relatively easily. They could add or change floors of wood or stone.

Poorer people – fishermen and such – lived in very small turf houses in Iceland: just a room or two, with perhaps another room up a ladder. The ground floor served as the work and storage space, and it was likely where cooking was done. Upstairs was the living space: sleeping and working in one room.

The two large turf houses in this article, though, belonged to wealthier families. You could see them as the equivalent of a manor house, even if they appear humble on the outside.

By far the best way to get around in Iceland is by renting a car and driving. At this site, you can compare the prices from all the major companies.

And speaking of getting around Iceland, here is the entire 3-week itinerary for a road trip around Iceland.

Laufás turf house

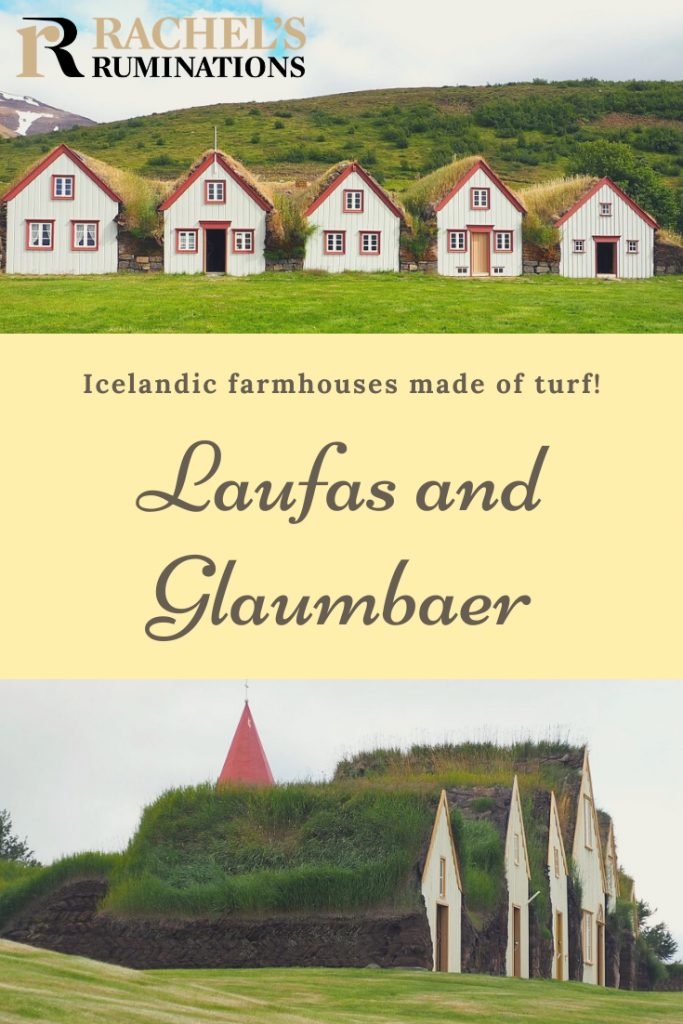

Laufas is a preserved example of a turf manor farmhouse. While it looks like a series of five row houses, it is actually one dwelling around a central hallway linking them all. Each “house” is a room, or sometimes two or three under one roof. In its current form, it dates to between 1866 and 1870, but it probably replaced other earlier turf houses on the site going back centuries.

Inside, the farmhouse is a mixture of very rough, unfinished spaces and remarkably well-furnished rooms, tastefully decorated. The entrance, for example, has a floor, walls and ceiling of bare wooden planks. Stepping through it, you enter an even less-finished narrow hallway down the center of the structure; it has stone and turf walls supported by wooden beams, and a dirt floor. Doorways along its length lead to the various rooms.

The parlor has neatly-painted paneled walls, tidy floorboards, and furnishings upholstered in red. Framed family photos hang on the walls. The dining room behind it is similarly furnished. These living spaces are on the outer sides of the house, so they have windows.

By contrast, some of the work and storage spaces are much simpler. In the original kitchen, for example, the turf walls are visible, and what served as the stove is made of rough stones. The fire in the hearth there could heat the house, and the smoke would escape through a hole in the roof. Upstairs there is a more modern kitchen, added later, with a proper cast-iron stove.

Bedrooms are upstairs too, and the rooms up there have slanted ceilings. This particular farmhouse was quite prosperous, and the bedrooms are larger than you’d imagine from seeing the house from the outside.

Other rooms in the complex have had a variety of functions: a classroom, a workshop, a pantry, a bridal room (where the women sat during wedding parties), storage, a cold cellar, warehouses (including one for cleaning down from local ducks) and a smithy. It was a residence until as recently as 1936.

Laufas was home to the priest of the church next door. That dates to 1865, but along with the farmhouse, churches stood on this spot starting in the 11th century. It is a lovely example of a typical Icelandic style: a wooden structure, bright and colorful. Inside is a pulpit dating to 1698.

Laufas Heritage Site and Museum: Laufas, northern Iceland, about five hours’ drive from Reykjavik. Open daily 9:00-17:00 May 15-October 1. Admission: Adults 1800 ISK (€11/$13), Children free. Website.

Glaumbaer turf house

Glaumbaer farmhouse is part of a group of historical buildings that together make up Skagafjörður Heritage Museum, part of the National Museum of Iceland. It is very similar to Laufas, but larger, with six gables on the front instead of five, and a bigger complex of rooms behind them (13, if I counted correctly). Like Laufas, it has been here for centuries, and, like Laufas, it sits next to church. Also like Laufas, the walls are stone and turf, with turf roofs held up by wooden beams. This one was occupied until 1947.

Some of the ground-floor rooms at Glaumbaer are quite rough and unpolished. The walls are stone and turf, complete with tufts of dried grass. It has a similar unfinished central hallway to Laufas, but longer, with small, steep stairways – more like ladders – leading off it to the upstairs rooms. Like at Laufas, the living spaces are more “modern” than the work spaces.

Glaumbaer’s baðstofa

As we were exploring the warren of rooms, we noticed a group of people dressed in traditional outfits. They followed us upstairs into a long room under a slanted roof. Like many upstairs spaces in Icelandic turf houses, this room, called a baðstofa, has a row of beds on either side. It would have served both as a bedroom and as a living and working space.

According to the flyer we received at the door, this room held up to 22 people, men and women, in 11 beds. The owner/farmer (who was the priest of the church next door), and his wife had the privilege of sleeping in the separate compartment at the end of the baðstofa. His laborers probably occupied the rest of the beds. Each would sleep, work and eat on his or her own bed. The women stayed on the side with the windows, since they needed light for their needlework.

At night, people slept two people to a bed, still dressed in their woolen clothing since the baðstofa was unheated. Their bedboards would keep them from falling out, and also keep their bedding well tucked in.

A musical interlude

Anyway, this group of people who had followed us upstairs – five or six women and one or two men – stepped ahead of us and sat themselves down on the beds on either side of the long room. The women quickly settled into doing various handicrafts like knitting and spinning yarn.

At the end of the room, a man in traditional clothing sat on a chair and settled in with a musical instrument in his lap. More people, dressed in modern clothes, crowded into the room as well. It became clear that a concert of sorts was about to begin.

I stood there in the center of the room along with Albert, unsure of what to do. Normally I love stumbling into events like this and was curious to hear what sort of music this man would play.

At the same time, it was July 2020, in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic. This room had too many people in it, too close together, and some of them, particularly the ones in traditional dress, seemed older. No one seemed very concerned, though. One of the spectators, a tourist sitting on one of the beds, indicated the space next to her that was free and gestured to me to sit down.

I plunked myself down on the bed, as did my husband on a free chair nearby. I pulled my scarf up over my mouth and the concert began.

Use the map below to book your accommodations in Iceland. Zoom in to see your options in the towns where you plan to stay.

The instrument the man played sounded much like a sitar, and it lay flat on his lap as he played, using a bow like a violin’s. Another musician playing a guitar accompanied him and they performed two beautiful ballads, one instrumental and one in French.

I couldn’t enjoy the music very much, though. All my anxieties about the pandemic woke up – anxieties that had all but disappeared traveling in the wide-open spaces of Iceland.

I knew that Iceland had had nearly zero cases when we arrived. But I also knew that about 2000 people were arriving every day, and that, despite required testing on arrival at the airport, some probably had the virus. Here I was, sitting in a crowded room with a bunch of random tourists.

After two songs, Albert and I left, just to get away from the crowd. I breathed easier outside.

Continuing the tour

Once we’d finished exploring all the rooms – parlor, kitchen, pantries, bedroom (for male students of the priest), dairy, guest rooms, storerooms and a smithy – we moved on to the other two historical buildings in the Skagafjörður Heritage Museum.

Both of these wooden houses date from the 19th century. One of them houses the museum’s offices and gift shop. The other has what looks like a very cozy tea room downstairs. Upstairs is an exhibition that is worth visiting. The rooms are decorated to period, meaning the late 19th century when people gradually moved away from turf houses in the country to wood houses and reinforced concrete structures in the bigger towns. Here you’ll see all sorts of handicrafts: brightly painted trunks, for example, and carved eating pots and children’s toys and so on.

To me, the church at Glaubaer isn’t quite as pretty as the one at Laufas, but you might as well look in while you’re there.

Skagafjörður Heritage Museum: Varmahlid, in northern Iceland, about four hours’ driving from Reykjavik. Open daily 10:00-18:00 from mid-May to end of August; Monday-Friday 10:00-16:00 in September-December and February-March; daily 10:00-16:00 in April until mid-May. In December only open by appointment. Admission in 2020: 1000 ISK (€6/$7) for adults, children 0-17 free. Website.

Other Icelandic turf houses

Laufas and Glaumbaer are two Icelandic turf houses that give a good impression of Icelandic life before the advent of timber or concrete houses in the 20th century. Both are fully furnished and have become museums for Icelanders and tourists to learn about Icelanders’ history.

However, they are not the only turf houses that are open to the public. There are many more, and some can give a more well-rounded view of other, less affluent, parts of Icelandic society. We only saw a few other ones, but I think they’re also worth a mention.

Fisherman’s cottage at the Maritime Museum in Hellissander

The Maritime Museum in Hellissander is more of a museum of fishing than a true maritime museum. It has a large room devoted to fish and other sea creatures, as well as sea birds and the natural history of the sea around Iceland. The second room covers fishing and the fish-drying industry.

Apparently some people did not work as fishermen all year. They worked on the land – for landowners like the people at Laufas and Glaumbaer – in the summers and then their bosses sent them to work as fishermen at the coast. They lived in temporary huts with six to ten men in each hut.

Other people did cobble together a living as a fisherman all year, and they lived in simple cottages. They had no livestock because they owned no land. The turf house at the Maritime Museum is a replica of one of these cottages. The original was torn down in 1951, but not before it was carefully measured and plans could be drawn for rebuilding.

Unlike Laufas and Glaumbaer, which have five and six gables respectively, as well as a warren of rooms behind the gables, this little house has two low gables and that’s all.

The entrance on the left leads into a very low-ceilinged space; too low for me to stand up in. I assume it was used for storage.

Upstairs on the left is the house’s only finished space, a large room with a window at each end. Since it is right under the roof, the walls slant inwards and two single-sized beds line each side, for a total of four. This would mean that up to eight people could sleep there. When they weren’t outside fishing, this is where they would work and sleep. The floors here are neat floorboards and the walls are wood paneling.

The entrance on the right leads into a single room with a peaked ceiling. Because of the single window, it gets a bit of light, but this was probably not a living space either. The floor is stone. At one end is a rough stone hearth for cooking. Presumably the space also served as a pantry, and perhaps, since it would be warm from the cooking fire, people might sit and eat here too.

The walls are bare turf, this time in simple horizontal rows, not in a herringbone pattern like at Laufas and Glaumbaer, and the rows of turf alternate with rows of stone. The ceiling is wooden planks supporting a layer of turf.

The Maritime Museum: Hellissandur. This is in western Iceland, near the tip of the long peninsula between the Westfjords and the southern peninsula (where Reykjavik is). From Reykjavik it’s about a three-hour drive. Open daily 10:00-17:00. Admission: Adults 1300 ISK (€8/$9.50), Children 0-16 free. Website.

If you’re thinking of travel to Iceland, you might also enjoy reading my article on whale watching in Husavik, or the one I wrote about a hike to have a soak in a hot spring thermal river!

Skogar Museum

We saw two turf farmhouses at Skogar Museum in the south of Iceland as well. You can read about them and see photos in my earlier article about Skogar. Both are smaller and a bit less fancy than either Laufas or Glaumbaer, but decidedly more upscale than the one a