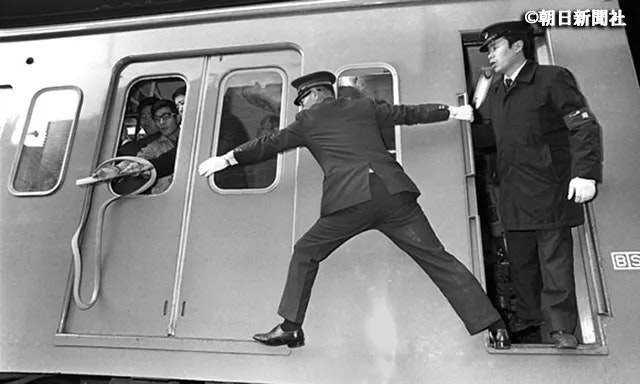

A train operator (or subway pusher?) holds onto rail as a window is busted open showing a packed train

Imagine a city whose suburbs have outsized the core in a span of few years. Thanks to an economic boom and a severe housing crunch, residents are increasingly pushed to the outer ring of the city. Due to an influx to the outer areas, train services quickly become outstretched to its limits. Crowds pack the trains during rush hour, leaving no wiggle room inside cars. Decades of lack of major investments exacerbate the issue. Frustrations mount at the lack of progress.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, these were predicaments ailing probably any North American metropolis. But this scenario sums up an unlikely city in an unlikely time: Tokyo in the 1960s.

Thanks to a massive population boom in the 15 years after World War II, Tokyo and its satellite cities – such as Saitama, Yokohama and Chiba – saw their populations nearly double in total from 9.78 million in 1945 to 17.86 million in 1960.1 Despite a population expanding outwards to find affordable housing, the main work centers remained in the core of Tokyo. This growing job-to-housing imbalance in the suburbs put severe pressure on the long-standing regional rail lines in the Greater Tokyo Area.

In 1965, the Japanese National Railways launched arguably its most transformative rail infrastructure project in postwar Japan not named Shinkansen: the Commuting Five Directions Operation (通勤五方面作戦, tsukin-gohomen-sakusen). It was an ambitious package of infrastructure improvements to significantly add capacity on five trunk lines connecting Tokyo to nearby cities in five directions. This was accomplished through any means necessary: adding extra tracks on the same right-of-way; diverting rider demands with new lines and extensions; and/or separating or even seizing freight lines to make space for passenger rail lines. This was a marked change in JNR’s approach to regional rail as well, a full pivot from a JNR which once claimed this is an issue metropolitan governments should entirely handle with better distributed housing policies and projects.

The work in total took nearly two decades to complete. While crowded trains in Tokyo never went away (the “subway pushers” were a thing then and a thing now), JNR’s goal of relieving crowding – with expected population growth accounted for – was accomplished, as all five lines saw crowding percentages decrease despite ridership increasing manifold. In addition, the substantially added capacity unlocked many new potentials in Tokyo’s rail network which became integral to its regional economy and quality of life. In the grand scheme, it became the skeletal foundations from which a thriving and profitable JR East, the privatized descendant of JNR, was able to blossom from.

A commute on the Chuo Line, also nicknamed “Murder Line”. Watch the whole video

Methodology and Background

Unlike my Seoul Metro Line 9 post, which made heavy use of my Korean mother tongue, Japanese is a language I have no familiarity with. Research took three-plus months of collecting sources in Japanese (or English, as occasionally lucky) as broadly as I can and translating them all using Google Translate — and mostly translating again somewhere else if the passages are translated nonsensically. The scarcity of English written materials on Japanese rail history has been very frustrating, and this has proven to be a very labor-intensive post to research and write.

I fully acknowledge that I may have blind spots or inaccuracies in this report easily identifiable to those who are fluent in Japanese or in Japanese rail history. As a former newspaper reporter, I gave my due diligence to this work but I will happily review any requests to correct any factual inaccuracies and clarify any mistranslation or misunderstanding.

I also made the difficult decision to split the piece into two to better allow both to shine on its own merits. Part II will focus on the legacies of the Commuting Five Directions Operation.

A Quick Geography Lesson

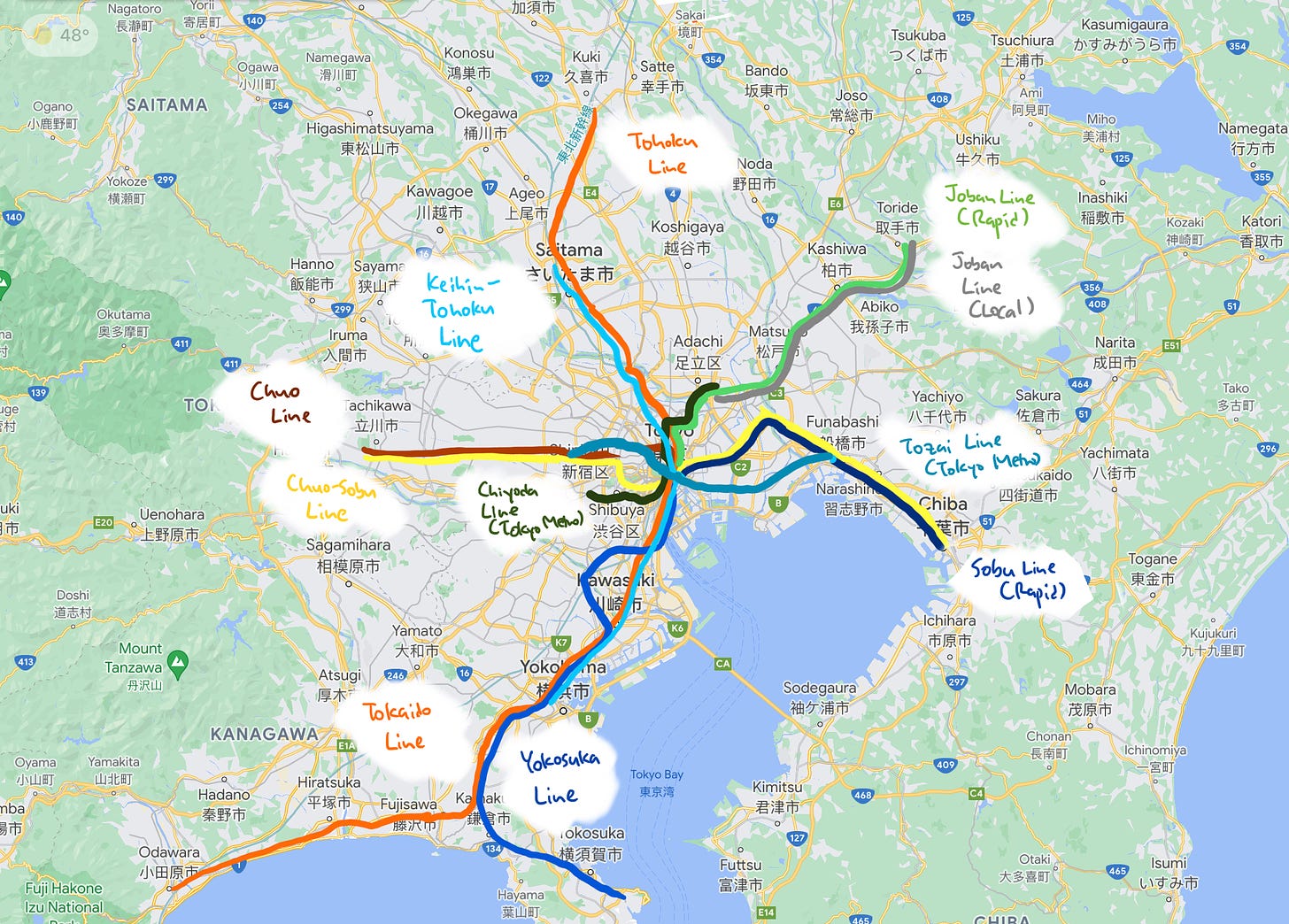

Tokyo is a sprawling metropolis with so many satellite cities and train lines that it can be easily intimidating to follow along. Japanese rail networks are commonly identified by a line name, often either a portmanteau of two endpoint cities or just the terminus point. I will not be able to list nor delve into the several dozen passenger rail lines which crisscross the Greater Tokyo Area. But I do want to take a moment to identify the train lines I will be referring to repeatedly and the directions they go from central Tokyo as a compass for the reader:

Five main lines:

-

Tokaido Line: Runs southwest from Tokyo.Full route connects to Osaka and Kyoto. The regional line connects Tokyo to Yokohama and Odawara (near Mt. Fuji)

-

Chuo Line: Runs west from Tokyo in a straight line.

-

Tohoku Line: Runs north from Tokyo. Connects Tokyo to Saitama.

-

Joban Line: Runs northeast from Tokyo.

-

Sobu Line: Runs east from Tokyo. Connects Tokyo to Chiba

Secondary lines:

-

Yokosuka Line: Runs south from Tokyo. Runs parallel with Tokaido Line from Tokyo until Ofuna and turns east.

-

Keihin-Tohoku Line: Runs north-south through Tokyo. Connects Saitama, Tokyo and Yokohama. Runs on both Tohoku Line and Tokaido Line

-

Chuo-Sobu Line: Runs west-east through Tokyo, does NOT go through central Tokyo. Runs on both Chuo and Sobu trunk lines

-

Chiyoda Line (Tokyo Metro): Connects southwest suburbs of Tokyo (including Shinjuku) to northeast suburbs of Tokyo. Runs parallel to Joban Line in northeast side

-

Tozai Line (Tokyo Metro): Connects west and east of Tokyo through Koto City and Edogawa sitting by the Tokyo Bay. Its two terminus stations – Nakano in the west, and Nishi-Funabashi in the east – also are Chuo-Sobu Line stations.

A hand-drawn regional rail lines of the Greater Tokyo Area to show its orientation and clarity in understanding the Commuting Five Directions Operation. Not every small directional turns for every line may be entirely accurate but I vouch for its directional accuracies.

Tokyo’s Rebirth and its Metropolitan Crises, 1945-1965

In 1945, the year Japan unconditionally surrendered to the Allies in World War II, the Greater Tokyo Area was hollowed out in population by the near-daily bombings and economic destruction. The Greater Tokyo Area’s population (which includes the four Tokyo, Saitama, Chiba and Kanagawa prefectures) dropped 27% from its 1940 peak from 12.74 million to 9.37 million; Tokyo alone saw a 48% decline from 7.35 million to 3.49 million.2

Japan – and Tokyo, especially – recovered from its postwar ruins at breakneck speed. Thanks to the Korean War from 1950 to 1953, Japan’s industrial production expanded rapidly, with factories, plants and offices mushrooming inside Tokyo’s city limits. By 1950, the Greater Tokyo Area recovered its wartime population loss at 13.05 million. By 1960, the area added nearly 5 million residents at 17.86 million.3

For the first 15 years of postwar recovery, Japan focused on providing massive amounts of public housing to address both rapidly growing demand in the war-scarred Greater Tokyo Area and the existent poor quality housing stock constructed organically out of postwar ruins. Shoddily built and densely packed wooden apartments proliferated in Tokyo; a dense area of these buildings were formed around the popular ring-shaped Yamanote Line earning the moniker “wooden rental apartment belt.”4 To replace unplanned and high-disaster risk housing stock, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government and other newly formed public housing corporations built massive quantities of high-rise public housing as close to the city center as possible.5

In the 1960s, the Japanese government adjusted its housing policies as worker income and standard of living quickly rose. The government began pushing for home ownership and began building massive construction projects in the outer parts of the Greater Tokyo Area. Public housing projects in Tokyo city limits proved increasingly difficult to construct as land prices soared in Tokyo under a booming economy.6

The 1960s brought new transportation modes to Tokyo. Higher worker incomes fueled the appetite for the automobile. The number of privately-owned automobiles in Tokyo tripled in eight years, from 490,000 in 1959 to 1.54 million in 1967.7 Under the guise of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, the Japanese government funded expressways and wider roads for the car to better roam the metropolis. As the Tokyo streetcar network was sacrificed to make space for the car, Tokyo aggressively expanded its subway lines to buffer its urban mass transport systems.8 In the 1960s, five lines for both Tokyo Metro and Toei Subway opened. (Including the Chiyoda and Tozai Lines which we will visit later)

The automobile or the new subway lines could not ameliorate the growing crisis in the most popular mode of transport in the Greater Tokyo Area: regional rail lines. Despite some of the lines being the oldest in Japan, regional lines carried the growing weight imposed by Japan’s suburbanizing housing policy, the continued jobs concentration in central Tokyo and displacement of Tokyo residents to the suburbs due to rising rents. From 1955 to 1964, Tokyo’s western suburbs and surrounding prefectures added 830,000 daily commuters to an already packed commute ridership.9

The government-owned Japanese National Railways (JNR) tried in vain to improve the commute experience. They introduced new modernized rolling stock – the 101, 111 and 113 electric diesel units as some beloved examples for Japanese railfans – and ran more peak service to however the trunk lines can handle. But the commute crowding would not relent. Consider the following five major regional lines’ average congestion rate in 196510:

(A criteria set by the Railway Bureau of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, 100% congestion rate is every rider in a train car being able to get a seat, grab a hanging strap or hold onto a bar. 250% is defined as “every time the train sways, my body becomes slanted and can’t move, my hands are immobile”)11

-

Tokaido Line: 251%

-

Chuo Line: 256% (Author’s note: the video of the Chuo Line commute says congestion rates were above 300%)

-

Tohoku Line: 219%

-

Joban Line: 261%

-

Sobu Line: 288%

The dangerous crowding levels proved highly fatal when a train was involved in an accident. In 1962, a freight train and three consecutive passenger trains on the Joban Line collided, killing 160 passengers and injuring 296 in the Mikawashima Accident.12 In 1963, two passenger trains collided with a derailed freight train on the Tokaido Line, killing 162 passengers and injuring 120 in the Tsurumi Accident.13

With forecasted population growth at nearly the same rate into the late 1960s and 1970s in the Greater Tokyo Area, JNR found itself in an impossible position. It had to plan for a future ridership when current ridership was already suffocating. With car ownership skyrocketing across Japan, JNR was already seeing its near-monopolistic market share in passenger traffic decline in the early 1960s.14Nothing short of a radical rebuild of their most reliant infrastructure may be able to rescue them out of this crisis.

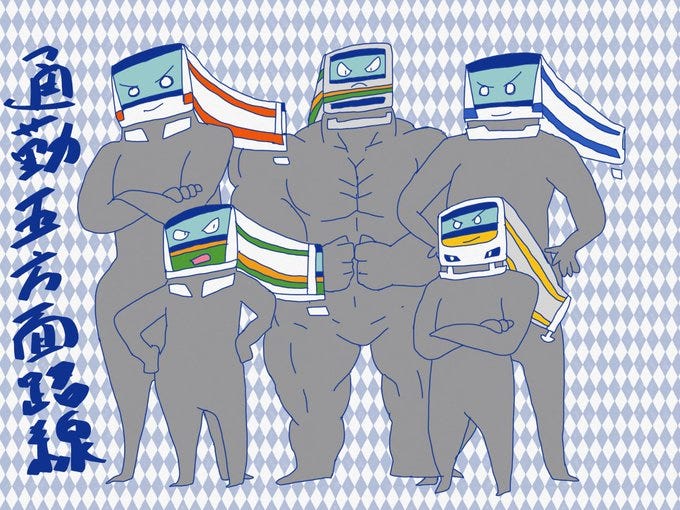

Spirits of the five lines of the Commuting Five Directions Operation. A go