Catch-up service: The Social Media Cage Fight

Barbearheimer

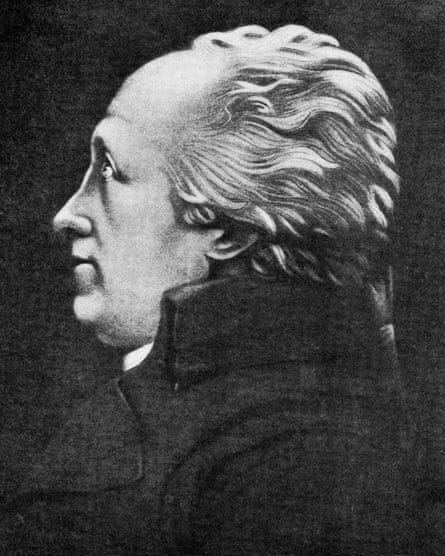

This is Henry Cort. You probably haven’t heard of him unless you’re an Industrial Revolution nerd (I hadn’t until this week). He isn’t as well known as James Watt or Joseph Priestley – he wasn’t one of the Lunar Men – but Cort played a critical part in the creation of the modern world. He invented a method of production which made it much easier and cheaper to turn scrap iron into high-quality iron, ready to build railways, warships, bridges and balconies.

Cort pioneered and combined two innovations. One was an improvement on Peter Onions’s puddling process, which we needn’t dwell on here – really, I just wanted to write out, “Peter Onions’s puddling process”. The other was the use of grooved rollers. Traditional rolling mills used flat rollers to roll hot metal into simple, flat shapes. Cort’s rollers had grooved edges which made for perfectly smooth, welded bars.

The “Cort process”, introduced in the 1780s, led to a quadrupling of Britain’s iron production over the following twenty years, making Britain one of the world’s leading iron producers. Fifty years after his death, the Times called Cort “the father of the iron trade” and today he’s regarded as one of the twenty or so most important innovators of the era.

Now comes a twist in the tale. A lecturer in science and technology at UCL called Jenny Bulstrode has published a paper which argues that what she calls “the myth of Henry Cort” is based on a lie.

In the prestigious journal, History and Technology, Dr Bulstrode argues that Cort stole his innovations from black slaves who had developed them independently in an iron works in Jamaica. Bulstrode traces a complex chain of events by which Cort, who as far as we know never visited Jamaica, ended up claiming credit for a process which was collectively invented by 76 enslaved factory workers (Bulstrode refers to them as “Black metallurgists”).

Bulstrode’s paper centres on a Jamaican ironworks run by an English industrialist called John Reeder. Within a few years of setting up, his foundry became successful and profitable. Reeder’s workforce included slaves trafficked from West Africa and trained by English experts he shipped over. Bulstrode argues that the black workers, drawing on ancient African traditions of ironwork, and from their experience of sugar production (where a kind of grooved roller is used) developed these new methods of their own volition, and that it was this which accounted for the factory’s impressive profits.

So how did Cort find out about it? Well, he ran an ironworks in Portsmouth, which he took over in 1775. Bulstrode notes that in 1781 a man with the surname of Cort arrived in Portsmouth from Jamaica. She describes him as a ‘cousin’ of Henry Cort, although as she notes, that term was often used to mean a distant relative. This second Cort had no connection to Reeder’s mill either, but Bulstrode argues that he must have heard all about the foundry and its innovative process when he was in Jamaica. She says he then met Henry Cort in Portsmouth, and passed on this valuable information.

A few months later, in 1782, Reeder’s factory was razed to the ground under orders from the British government. This was previously thought to have been because the colony was under threat from rival European powers and the British wanted to prevent the foundry from falling into French or Spanish hands. Bulstrode says that the military governor disclosed an ulterior motive: the British wanted to stop the factory from being taken over by black Jamaicans, who might then be empowered to overthrow their colonial rulers (in an interview with a podcast called The Context of White Supremacy, Bulstrode even suggests that Henry Cort instigated the destruction via contacts in the British government). Bulstrode says that components from the destroyed factory were then shipped to Portsmouth, with the implication being that Cort then reverse-engineered the process, and patented the secrets under his own name.

Bulstrode’s paper has made a big splash. It’s been hailed by her academic peers as a major breakthrough, and picked up by big media outlets including the Guardian, the New Scientist, and NPR. If you Google “Henry Cort”, it’s these reports which come up. Wikipedia has already incorporated it into Cort’s biography. Bulstrode’s paper fits the zeitgeist in historical studies – that the economic success of Britain and the West owes much more to the exploitation of black ingenuity and ideas than mainstream historians have hitherto allowed for.

If the story Bulstrode tells sounds incredible, that’s because it is. Right after Bulstrode’s paper made the headlines, Anton Howes, the proprietor of an excellent Substack on the history of innovation, noted the almost total lack of evidence for the paper’s central claims. Last week, he returned to it in a piece sparked by a new paper from Oliver Jelf which examines Bulstrode’s paper in detail and provides the most thorough debunking of it imaginabl