Risk-free rate

In 1964, William F. Sharpe introduced a theory of capital asset pricing[1], commonly referred as Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). Today, CAPM is the foundation for modern financial asset price theory[2]. For his work, Professor Sharpe of Stanford University received the 1990 Nobel Prize in Economics for his foundational contribution to financial economics[3].

The CAPM assumes the existence of a type of riskless asset. If an investor invests in a riskless asset, the investor is guaranteed to receive a rate of return, called the risk-free rate.

This risk-free rate is a key input in the pricing of near all types of financial assets, including stocks, debt, options, and real estate. A fundamental assumption in valuations, the cost of capital is calculated from an assumed risk-free rate.

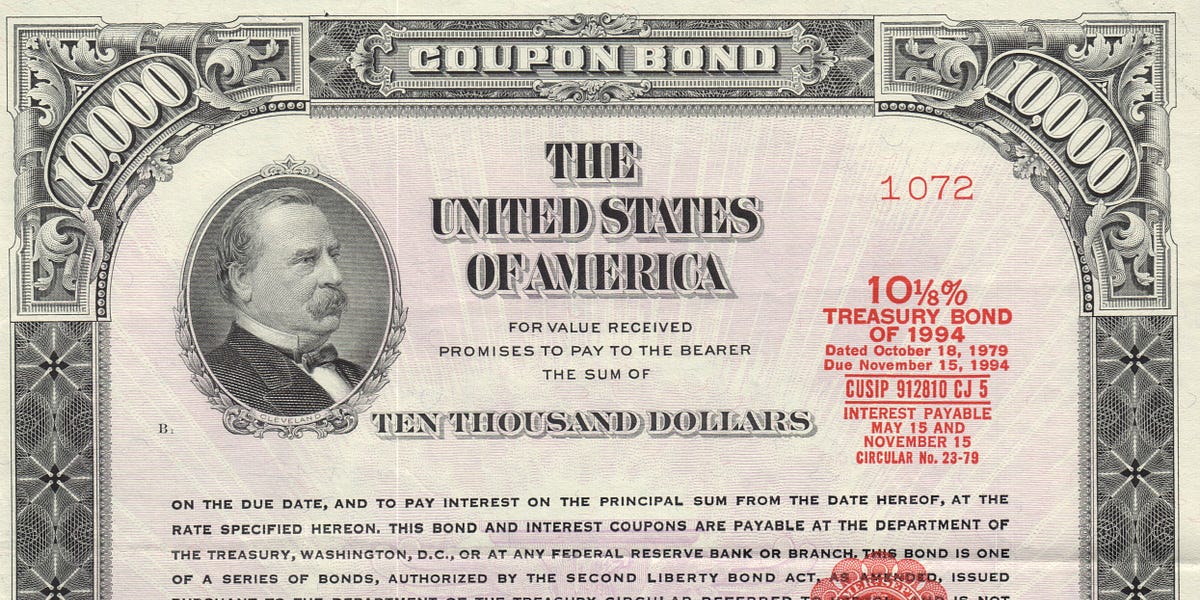

While choosing the best risk-free rate is quite literally an academic exercise[4]. The global financial system, for the most part, uses U.S. treasury yields[5] as proxies for the risk-free rate.

The global financial system assumes U.S. treasury debt is a type of riskless asset. In financial lingo, U.S. treasuries have zero credit risk. The investor assumes they will always receive their money on time:

-

Risk of U.S. treasuries defaulting = 0

So, what if risk > 0?

The United States federal government has never defaulted on its debt. Such an event has never been observed by the world. It will be unprecedented.

Since January 19, 2023, the United States federal government had been unable to issue more debt beyond its $31.381 trillion statutory limit[6]. As a result, the Department of Treasury projects that the federal government will run out of money on June 1, 2023[7]. If the debt limit is not raised by then, the United States will default on its