Gravitational lenses are rare in the sky – galaxies bending the light-paths of light from other galaxies behind them to form distorted or even multiple images. Even rarer is a perfect alignment of the two galaxies with us, the obervers, with the light being bent into a so-called Einstein Ring. And the rarest case was now observed by Euclid: this happening in an extremely nearby NGC galaxy.

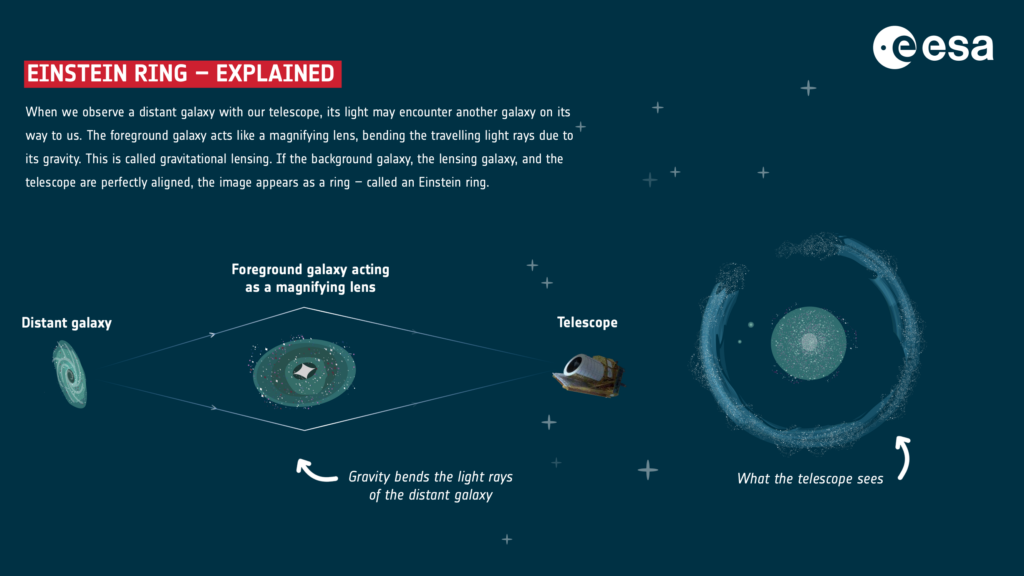

Gravitational lensing is the effect of mass bending space and light following along this bent space. If the masses are high enough, as for a galaxy, then this can lead to an image of an object behind a galaxy to be distorted or even split up into several images: a strong gravitational lens. If vary rare cases – for a perfect alignment of source, galaxy, and observer on a line – the image gets bent into a ring. These so-called Einstein Rings have been found before, but in all configurations only approximately 1000 gravitational galaxy–galaxy lenses are currently known across the sky.

The phenomenon of strong gravitational lensing has been first discussed already in the late 1700s, in the case of Newtonian gravity. But only Albert Einstein was able to calculate the correct angle of light-bending, using his General Theory of Relativity in 1915. In the years after, expeditions to properly measure the lensing effect for the mass of the sun during a solar eclipse then actually confirmed General Relativity based on the lensing effect. This was for the sun.

Coming back much more massive galaxies, the realisation that they could act as lenses – and image sources in the background – took until 1937 when Fritz Zwicky used the new knowledge about galaxies being really distant collections of stars like our own Milky Way. And in the 1960s it was realized that quasars, very bright, point-like active centers of galaxies, would make the perfect sources for lensing. And so it took until 1979, when the first “twin” quasar was found and identified as two images of the same background source – the first observed gravitational lens.

To dive deeper, the chance of a galaxy – or galaxy cluster – acting as a gravitational lens is highest for some intermediate distance from us observers, and for the source galaxy to be quite a bit further away. Most gravitational lens galaxies are therefore several billions of light-years away. So it’s extremely rare for lensing galaxies to be very close to us. A galaxy has to be very massive to have enough impact to create multiple lensed images, so what we would call “in our neighbourhood”, within a distance of 700 million light years, only 2400 galaxies exist th

2 Comments

sheepscreek

It still blows my mind when I come across images brimming with galaxies. How insignificant are we in the vast universe? Even our entire solar system, it’s likely not even a blip in the cosmic scheme. Just wow…

jl6

The bit I find amazing in these galaxy fields is the apparent randomness of the orientation of each galaxy. Why is this? Are we seeing a remnant of chaotic behavior where tiny random variations at the smallest scale in the early universe led to the wildly diverse objects that we see today? There is great variation in the color, size, and shape of galaxies too, but somehow it’s the apparent orientation that baffles my intuition.