It’s not every week that someone with my particular employment profile and expertise has something they’re knowledgable about become a hot topic of national discussion, but the release of OpenAI’s, ChatGPT interface generated a sudden flurry of discussion about how we teach students to write in school, which is something I know a lot about.

I’m never sure how much overlap there is for the various audiences that consist of the John Warner Writer Experience Universe, but while to folks here I am, “The Biblioracle,” book recommender par excellence, to a whole other group I am the author of Why They Can’t Write: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities, and The Writer’s Practice: Building Confidence in Your Nonfiction Writing, and a blogger about education issues at Inside Higher Ed.

Modesty aside, and somewhat to my surprise, I have become an expert in how we teach writing. That expertise was birthed from the frustration I experienced in trying to teach writing to first-year college students over the years, and finding them increasingly disoriented by what I was asking them to do, as though there was no continuity between what they’d experienced prior to college, and what was expected of them in college.

These were well-above average students at selective schools (University of Illinois, Virginia Tech, Clemson), who did not necessarily lack writing skill, but had very negative attitudes towards writing. To cut to the chase, and to keep from repeating everything I cover in Why They Can’t Write, rather than having students wrestle with the demands of trying to express themselves inside a genuine rhetorical situation (message/audience/purpose), they were instead producing writing-related simulations, utilizing prescriptive rules and templates (like the five-paragraph essay format), which passed muster on standardized tests, but did not prepare them for the demands of writing in college contexts.

My books are a call to change how we approach teaching writing at both a systemic and pedagogical level. What teachers and schools ask students to do is not great, but that asking is bound up with the systems in which it happens, where teachers have too many students, or where grades or the score on an AP test are more important than actually learning stuff. It’s not just that we need to change how and what we teach. We have to fundamentally alter the spaces in which this teaching happens.

It is difficult to overstate how bad things have been for a couple of generations of students. This tweet from the writer Lauren Groff (Matrix), lamenting what school had done to her son’s attitudes towards writing is a not uncommon testimony I hear from parents and students alike.

Deep down, this is a question about what we value, in what we read, what we write, and unfortunately, we have attached a set of values to student writing that are disconnected from anything we actually value about what we read, and what we write.

Along with many others, I’ve been shouting about these problems for years, often into what felt like a void, but this past week, once people had a chance to see what the ChatGPT could produce, suddenly attention was being paid.

It’s important to understand what ChatGPT is, as well as what it can do. ChatGPT is a Large Language Model (LLM) that is trained on a set of data to respond to questions in natural language. The algorithm does not “know” anything. All it can do is assemble patterns according to other patterns it has seen when prompted by a request. It is not programmed with the rules of grammar. It does not sort, or evaluate the content. It does not “read”; it does not write. It is, at its core, a bullshitter. You give it a prompt and it responds with a bunch of words that may or may not be responsive and accurate to the prompt, but which will be written in fluent English syntax.

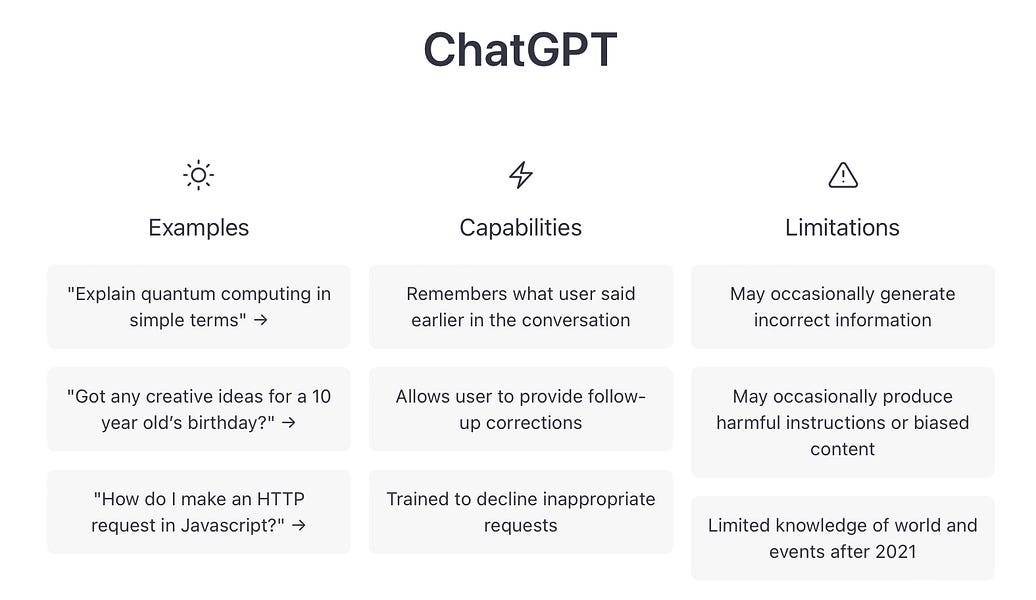

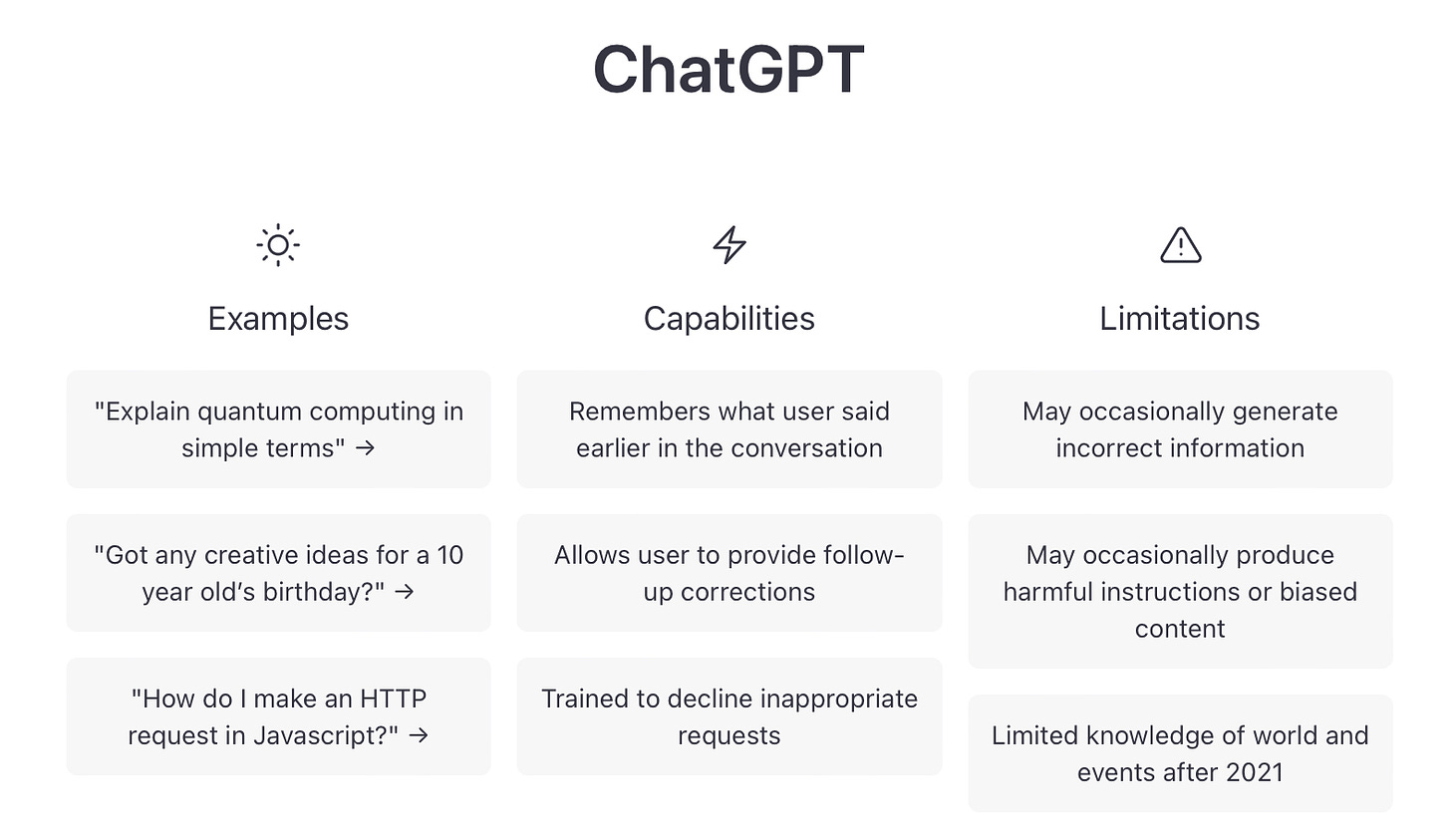

This snapshot from the ChatGPT homepage is a good overview of what OpenAI says ChatGPT can do.

I first wrote about the underlying algorithm (GPT3) at Inside Higher Ed back in March 2021, when it was put to the task of trying to answer some college-level writing assignments and then compared to the output of human students answering the same questions.

For three of the four subjects – research methods, U.S. history and law – the AI passed with a C or better grade. The top human scored better than the AI in each category, but in two categories (research methods, law), the AI beat one or more of the humans.

The subject it tanked was creative writing.

It would not tank creative writing anymore.

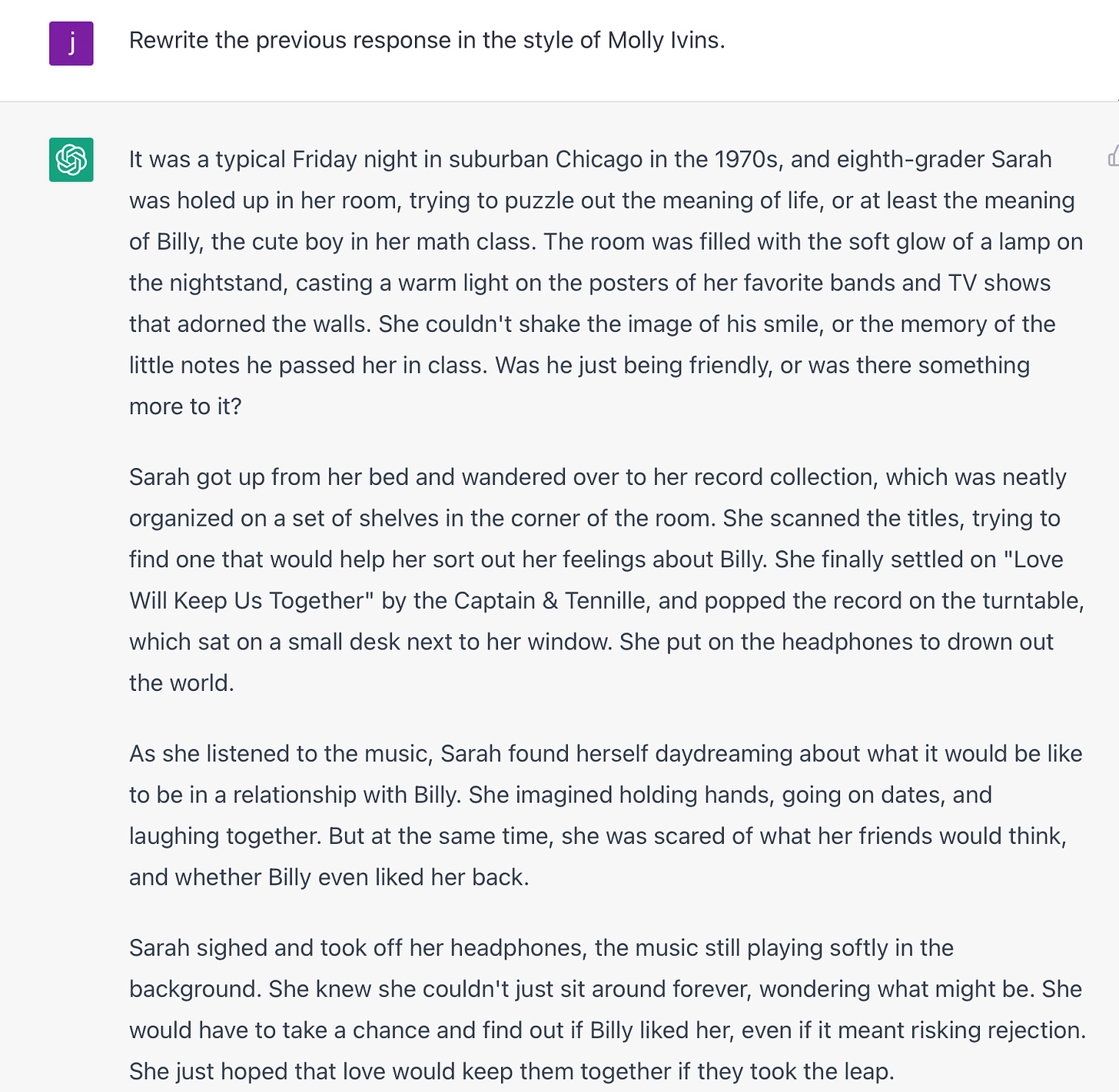

At the top next to the purple icon is my prompt. Below that is ChatGPT’s response. It took about 60 seconds for it to process and produce the text.

This is not good, exactly, but it also isn’t bad. It’s perfectly okay, not unlike the kind of thing that a student would produce in an introductory creative writing course. For a short story, that opening sentence is weird, but a clever student making a quick edit could excise it and improve the outcome immediately. In fact, a good overall editorial strategy would be to cut any line that’s explicitly in my prompt, so what remains is learned via inference. The weirdest part is perhaps the choice of song, as the upbeat spirit of the song and lyrics about a woman telling her partner not to be tempted by other girls doesn’t quite fit the scenario. It’s a good example of how the algorithm has no appreciation of meaning and context.

The passage also lacks a sense of place and atmosphere. The descriptions are sterile. I’m going to fix that with an additional prompt.

That’s actually starting to approach not bad. It’s not good, exactly, but in an introductory class, you don’t necessarily expect good. Still, it’s lacking something. It feels rather generic, voiceless. Let’s see if I can help it out a bit:

If you don’t know Molly Ivins, you should because she’s the best political commentary writer in the history of the genre, and she wrote in a very distinctive style.

This doesn’t actually sound like Molly Ivins writing about politics, but the prompt is enough to inject some spark of life into the prose. You can see a couple of immediate improvements over the previous version.

Compare these two sentences:

Eight grade student, Sarah sat on her bed in her room, staring at the ceiling as she thought about Billy, the cute boy in her class.

And

Eighth-grader Sara was holed up in her room, trying to puzzle out the meaning of life, or at least the meaning of Billy, the cute boy in her math class.

The latter is clearly better, more alive. “Holed up” and “puzzled out” are common phrasings, but clearly better than the generic language of the first example. And that line about puzzling out the “meaning of Billy” is downright good.

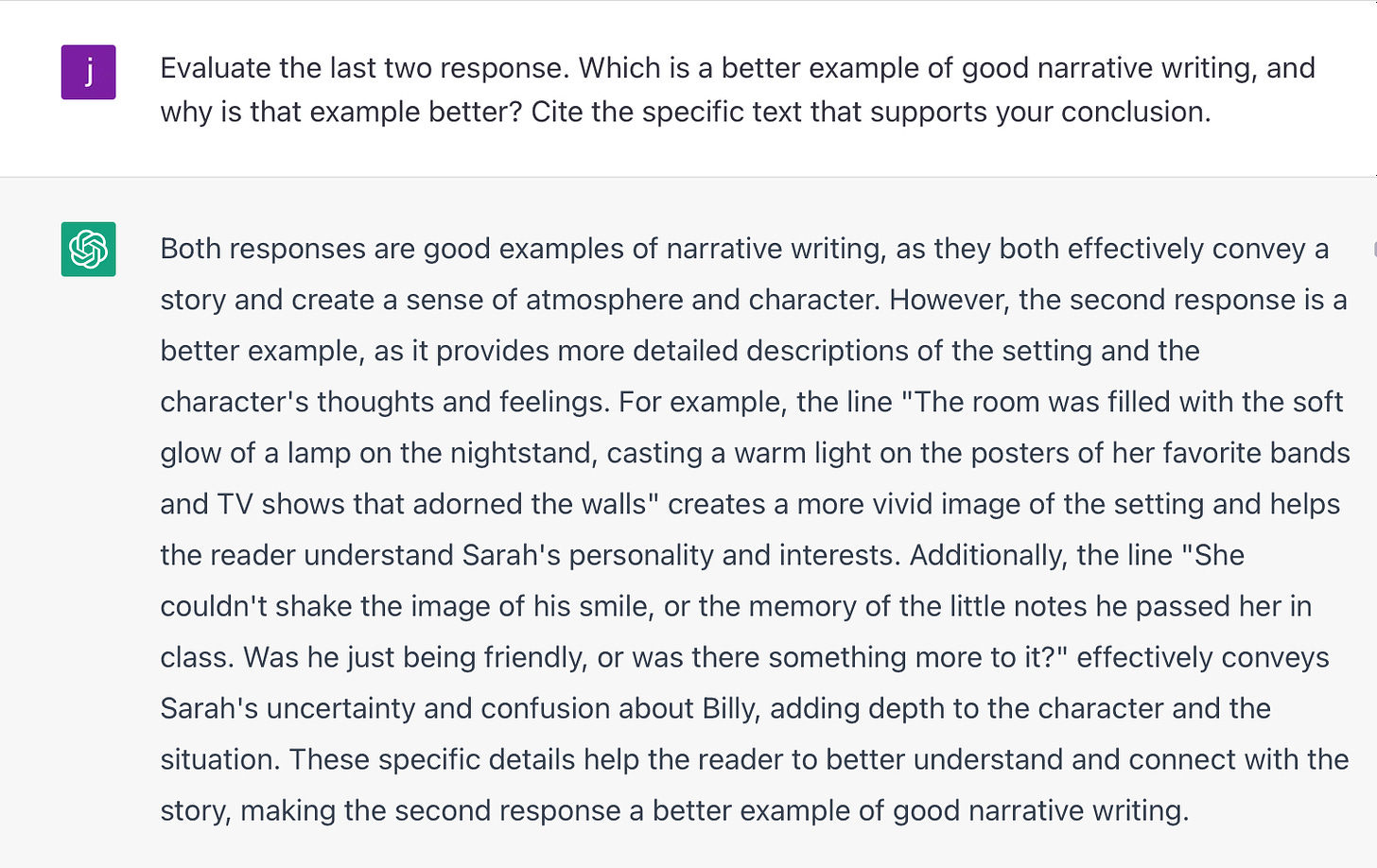

You know who agrees with me about which is the better narrative? ChatGPT.

If the AI can produce this, imagine what it can do with a canned prompt that you might commonly find in a literature-based high school English class, such as this one, from a sample AP Literature exam, “In many works of fiction, houses take on symbolic importance. Such houses may be literal houses or unconventional houses (e.g., hotels, hospitals, monasteries, or boats). Choose a work of fiction in which a literal or unconventional house serves as a significant symbol. Then, in a well-written essay, analyze how this house contributes to the interpretation of the work as a whole. Do not merely summarize the plot.”

I won’t bore you by pasting the answer, because it’s not worth your time to read it, but it would easily receive the maximum score a 5, particularly given the fact that the AP graders do not pay any attention to whether or not the content of the answer is accurate or true.

I cannot emphasize this enough: ChatGPT is not generating meaning. It is arranging word patterns. I could tell GPT to add in an anomaly for the 1970s – like the girl looking at Billy’s Instagram – and it would introduce it into the text without a comment about being anomalous. It is not entirely unlike the old saw about a million monkeys banging on a typewriter for along enough, that one of them would produce the works of Shakespeare through random chance, except this difference is, ChatGPT has been trained on a data set that eliminates all the gibberish.

Many are wailing that this technology spells “the end of high school English,” meaning those classes where you read some books and then write some pro forma essays that show you sort of read the books, or at least the Spark Notes, or at least took the time to go to Chegg or Course Hero and grab someone else’s essay, where you changed a few words to dodge the plagiarism detector, or that y