By demanding that morality tests be imposed on scientific journal authorship, Geoff Marcy’s critics are creating a dangerous precedent.

Are we alone in the universe? It’s one of the most compelling existential questions facing humanity. And the past half-century has witnessed a revolution in our ability to scan the cosmos in search of an answer. When I was a university student, the possibility of discovering, much less observing, planets in other star systems seemed like science fiction. But that has changed. Thanks to orbiting observatories such as the James Webb Space Telescope, and huge ground-based telescopes such as the Keck Observatory in Mauna Kea Hawaii, astronomers could be on the cusp of finding evidence for life around one or more of the thousands of extrasolar planets (also known as exoplanets) that have now been discovered.

And yet, even as new technology allows humanity to peer into distant galaxies and answer profound questions about the universe, some scientists working in this field are being hounded by colleagues more focused on leading terrestrial outrage mobs than finding new discoveries in the heavens.

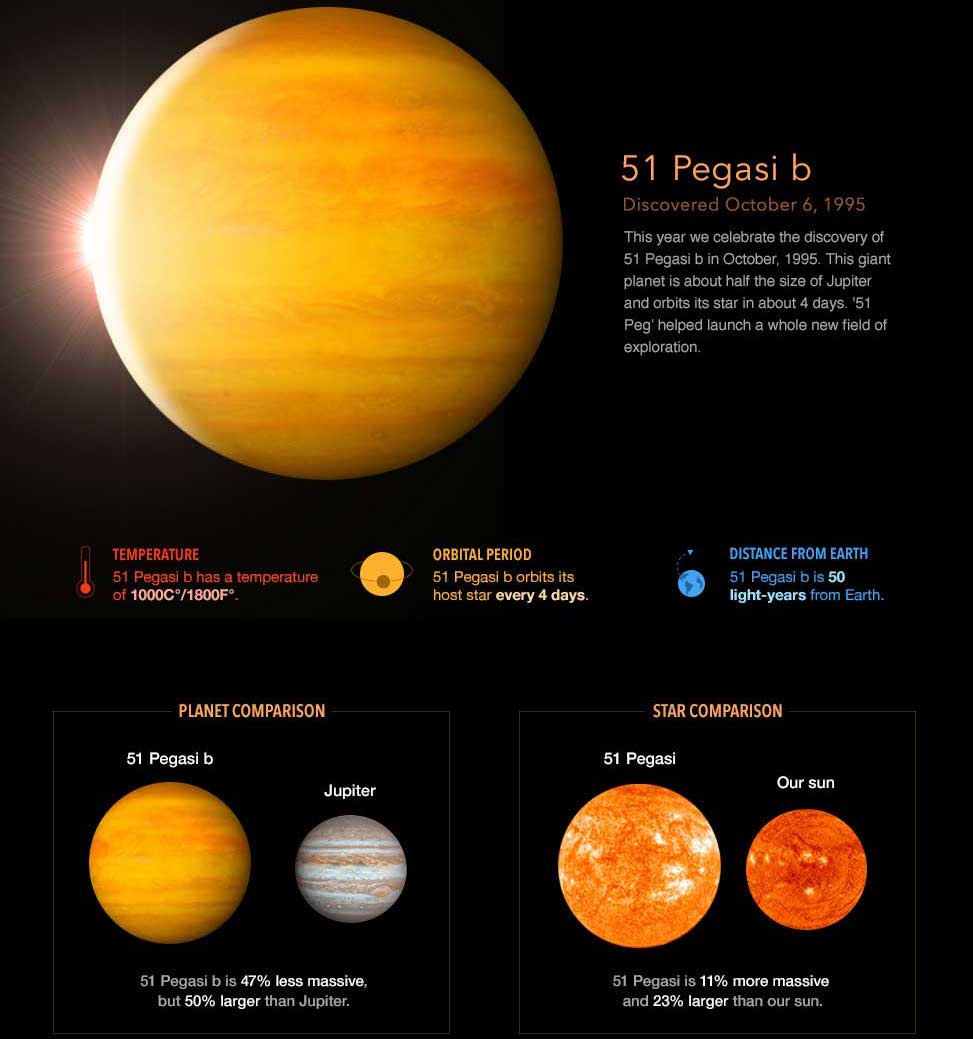

The existence of planets orbiting other main sequence stars (a category that includes about 90 percent of the stars in the universe) was first demonstrated in 1995, when Swiss astrophysicist Michel Mayor and Swiss astronomer Didier Queloz inferred the existence of a Jupiter-mass companion of the star 51 Pegasi, approximately 50 light years away from our own solar system. They did this by observing cyclic “wobbles” in the star’s path—tiny oscillatory movements whose maximum speed is about 70 meters per second, negligible in astronomical terms. These oscillations reflect the gravitational tug of 51 Pegasi’s planetary companion, which orbits the star once every four days, at a distance far closer than Mercury orbits our Sun.

The discovery was accomplished using a technique that Mayor and Queloz spearheaded in parallel with similar work done by American astronomer Geoff Marcy. Both teams based their observations on the Doppler effect, the well-known phenomenon by which a wave’s apparent frequency will change depending on whether the observer is moving toward, or away from, the radiation source. (It’s similar to the principle that police use to measure your car’s speed with a radar gun.) To the extent that a star’s wobble aligns with the axis of observation, the frequency of its emitted light, as observed on Earth, would also vary, albeit by a minute amount.

The two teams used sensitive spectrometers that could measure such shifts. And within a month of Mayor and Queloz’s observations becoming known, their results were confirmed by Marcy and his own colleagues. Marcy’s team went on to identify 70 of the first 100 known exoplanets, including the first exoplanet located as far from its star as Jupiter is from the Sun. In 2005, Marcy and Mayor shared the prestigious Shaw Prize in Astronomy, awarded for outstanding contributions in the field.

Another planet-detecting technique—which I will admit to having previously dismissed as nearly impossible—was uncovered by Marcy’s group, working with Tennessee State University astronomer Greg Henry. Using this method, a planet’s existence is inferred from the fact that its associated star is dimmed (to a terrestrial observer) by a minute amount (less than one part in a thousand) when the planet passes in front of it. This “transit” technique of exoplanetary detection was used by NASA’s 2009 Kepler Mission, of which Marcy was a Science Team member, to discover approximately 4,000 planets. Many of these are the size of our Earth, and would seem to have surface temperatures conducive to biology (as we know it).

By now, we have discovered many systems with multiple planets orbiting a single star. And this naturally invites the question: Is the character of our own solar system, with large giant gas planets (Jupiter, Saturn, and Neptune) orbiting farther out, and smaller rocky planets (Mars, Earth, Venus, and Mercury) orbiting closer in (allowing the surface of at least one of these latter planets, Earth, to be sufficiently warm to host liquid water), a prerequisite for the development of life?

In March, a group of 16 authors—including Marcy; lead author Lauren Weiss, a junior faculty member in the astrophysics group at Notre Dame University, and a former PhD student of Marcy; and Caltech astronomer Andrew Howard, a former postdoctoral researcher who’s worked under Marcy’s direction—posted a paper entitled ‘The Kepler Giant Planet Search. I: A Decade of Kepler Planet Host Radial Velocities from W. M. Keck Observatory’ to arXiv, an archive for electronic preprints of scientific papers in certain fields. One of the authors’ purposes was to explore how the existence of Jupiter-size outer planets might correlate with the existence of smaller rocky inner planets. (A layperson might ask what the existence of a gas giant such a Jupiter has to do with the emergence of life on a rocky planet much closer to the sun. One answer is that—to take our own solar system as a representative example—Jupiter is believed to have absorbed or deflected large asteroids and comets from the outer solar system that otherwise would have vaporized Earth’s oceans, from which life first emerged.) Here is part of the abstract of that paper:

Despite the importance of Jupiter and Saturn to Earth’s formation and habi