Getting those customers would require abandoning the company’s mechanical inertial-sensor systems in favor of a new, unproven quartz technology, miniaturizing the quartz sensors, and turning a manufacturer of tens of thousands of expensive sensors a year into a manufacturer of millions of cheaper ones.

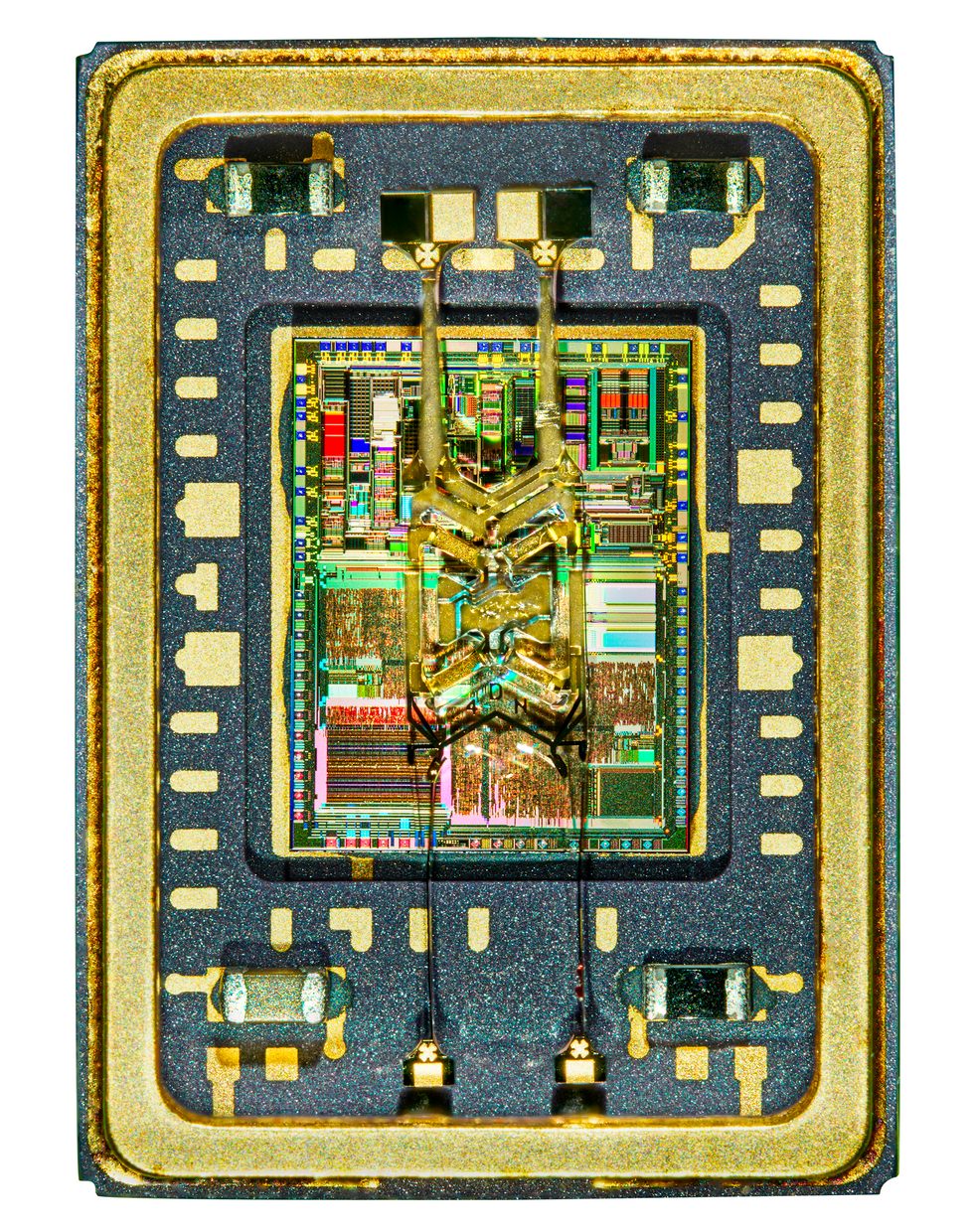

Madni led an all-hands push to make that happen—and succeeded beyond what anyone could have imagined with

the GyroChip. This inexpensive inertial-measurement sensor was the first such device to be incorporated into automobiles, enabling electronic stability-control (ESC) systems to detect skidding and operate the brakes to prevent rollover accidents. According to the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, in the five-year period spanning 2011 to 2015, with ESCs being built into all new cars, the systems saved 7,000 lives in the United States alone.

The device went on to serve as the heart of stability-control systems in countless commercial and private aircraft and U.S. missile guidance systems, too. It even traveled to Mars as part of the

Pathfinder Sojourner rover.

Vital Statistics

Name: Asad M. Madni

Current job: Distinguished adjunct professor, University of California, Los Angeles; retired president, CEO, and CTO, BEI Technologies

Date of birth: 8 September 1947

Birthplace: Mumbai, India

Family: Wife (Taj), son (Jamal)

Education: 1968 graduate, RCA Institutes; B.S., 1969, and M.S., 1972, University of California, Los Angeles, both in electrical engineering; Ph.D., California Coast University, 1987

Patents: 39 issued, others pending

Hero: My father, overall, for teaching me how to learn, how to be a human being, and the meaning of love, compassion, and empathy; in art, Michelangelo; in science, Albert Einstein; in engineering, Claude Shannon

Most recent book read: Origin by Dan Brown

Favorite books: The Prophet and The Garden of the Prophet, by Kahlil Gibran

Favorite music: In Western music, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Elvis Presley; in Eastern music, Ghazals

Favorite movies: Contact, Good Will Hunting

Favorite cities: Los Angeles; London; Cambridge, U.K.; Rome

Leisure activities: Reading, hiking, listening to music

Organizational memberships: IEEE Life Fellow; U.S. National Academy of Engineering; United Kingdom Royal Academy of Engineering; Canadian Academy of Engineering

Most meaningful awards: IEEE Medal of Honor: “For pioneering contributions to the development and commercialization of innovative sensing and systems technologies, and for distinguished research leadership”; UCLA Alumnus of the Year 2004

For pioneering the GyroChip, and for other contributions in technology development and research leadership, Madni received

the 2022 IEEE Medal of Honor.

Engineering wasn’t Madni’s first choice of profession. He wanted to be a fine artist—a painter. But his family’s economic situation in Mumbai, India (then Bombay) in the 1950s and 1960s steered him to engineering—specifically electronics, thanks to his interest in recent innovations embodied in the pocket-size transistor radio. In 1966 he moved to the United States to study electronics at the RCA Institutes in New York City, a school created in the early 1900s to train wireless operators and technicians.

“I wanted to be an engineer who would invent things,” Madni says, “one who would do things that would eventually affect humanity. Because if I couldn’t affect humanity, I felt that I would have an unfulfilling career.”

After two years completing the electronics technology program at the RCA Institutes, Madni went on to

the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), receiving a B.S. in electrical engineering in 1969. He continued on to a master’s and a Ph.D., using digital signal processing along with frequency-domain reflectometry to analyze telecommunications systems for his dissertation research. While studying, he also worked variously at Pacific States University as an instructor, at Beverly Hills retailer David Orgell in inventory management, and at Pertec as an engineer designing computer peripherals.

Then, in 1975, newly engaged and at the insistence of a former classmate, he applied for a job in Systron Donner’s microwave division.

Madni’s started at Systron Donner by designing the world’s first spectrum analyzer with digital storage. He had never actually used a spectrum analyzer before—these were very expensive instruments at the time—but he knew enough about the theory to talk himself into the job. He then spent six months working in testing, picking up practical experience with the instruments before attempting to redesign one.

The project took two years and, Madni reports, led to three significant patents that started his climb “to bigger and better things.” It also taught him, he says, an appreciation for the difference between “what it is to have theoretical knowledge and what it is to commercialize technology that can be helpful to others.”

He went on to develop numerous RF and microwave systems and instrumentation for the U.S. military, including an analyzer for communications lines and attached antennas built for the Navy, which became the basis for his doctoral research.

Though he moved quickly into the management ranks, eventually climbing to chairman, president, and CEO of Systron Donner, former colleagues say he never entirely left the lab behind. His technical mark was on every project he became involved in, including the groundbreaking work that led to the GyroChip.

Before we talk about the little quartz sensor that became the heart of the GyroChip, here’s a little background on the inertial-measurement units of the 1990s. An IMU measures several properties of an object: its specific force (the acceleration that’s not due to gravity); its angular rate of rotation around an axis; and, sometimes, its orientation in three-dimensional space.

The GyroChip enabled electronic stability-control systems in automobiles to