Was Rembrandt van Rijn a bad student? Birgit Boelens, a conservator at the Hermitage Amsterdam art museum and curator of the 2023 exhibit titled Rembrandt & His Contemporaries, hesitates. One would think that someone with Rembrandt’s innate talent must have been a bit of a rulebreaker, but this was not necessarily the case. “He certainly had a mind of his own,” Boelens says. “But above all, he was curious and eager to learn, and his teachers appreciated that.”

During the Dutch Golden Age, aspiring painters started their careers working as apprentices in the studios of established artists. From his teacher, Pieter Lastman, Rembrandt learned how to make history paintings. Combining portraiture, figure painting, architectural painting, and still life, this genre was long considered the pinnacle of artistic expression. As an apprentice, Rembrandt not only inherited Lastman’s affinity for creating grand, complex images but also his ability to imbue scenes from the past with a contemporary significance.

Just as Lastman’s David Gives Uriah a Letter for Joab (1619) treated the rivalry between the Israeli king and his general as a reflection of the deteriorating relationship between Maurice, Prince of Orange, and the (beheaded) grand pensionary Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, so does Rembrandt’s Conspiracy of Claudius Civilis (1661), which depicts the ancient inhabitants of Holland rebelling against the Romans, mirror the Eighty Years’ War in which the Netherlands sought to liberate itself from the Spanish Empire.

The study of Rembrandt’s education dispels one of the biggest myths in art history. We tend to place iconic painters in a vacuum, picturing them painting in their studios or nature, removed from the outside world and its distractions. However, this could not be further from the truth. The art market in which Rembrandt operated was a tightly interwoven ecosystem, and exhibits like Rembrandt & His Contemporaries trace how stylistic influence pass from one generation of artists to the next.

Rembrandt studied under Lastman for only six months. Others trained for more than eight years. He was also only 22 when he opened his own studio with apprentices Gerrit Dou and Isaac de Jouderville, who paid him an annual fee of 100 guilders in exchange for his tutelage (the equivalent of $6,000 today). Dou and Jouderville made copies of Rembrandt’s works and even helped him with commissions. It’s been said that large parts of The Night Watch were painted by his pupils, with Rembrandt focusing on the design and the finish. Dou and Jouderville also learned how to mix paints — a complicated practice before the age of chemistry and art supply stores.

The paintings on display at the Amsterdam Hermitage reveal how strong an impact Rembrandt left on his apprentices. Boelens points towards Carel Fabritius, whose painting Hagar and the Angel (1645) could easily be mistaken for a Rembrandt. In the Bible, Hagar was a slave impregnated by Abraham, the father of Judaism, because his wife, Sara, couldn’t have children. When Sara found out, she sent Hagar and her newborn son Ishmael out into the desert. With Ishmael at death’s door, a weeping Hagar fell onto her knees to pray for his survival. Fabritius chose to depict this moment from the story, doing so with a sensitivity that rivals his master.

“It’s emotional, but not sentimental,” Boelens says. “Her despair is completely and utterly believable.”

Fabritius is widely recognized as the most gifted of Rembrandt’s apprentices, as well as the one who most closely followed his style. Unfortunately, Fabritius died in 1654 at the age of 32 when a gunpowder store exploded in the city of Delft. The explosion killed more than 100 people and injured thousands more. It not only took Fabritius’ life but also incinerated many of his paintings. Hagar and the Angel was preserved, but one wonders what its creator could have achieved had he lived even a little bit longer.

Rembrandt’s style evolved drastically throughout his career. Initially, the painter followed the Dutch tradition of Lastman and others, applying a painstaking finish to his work. In time, however, Rembrandt’s paintings increasingly came to resemble his sketches: loose, expressive, and borderline abstract. Brushstrokes, previously blended to the point they were hardly noticeable, were rapidly smeared across the canvas to reveal his process.

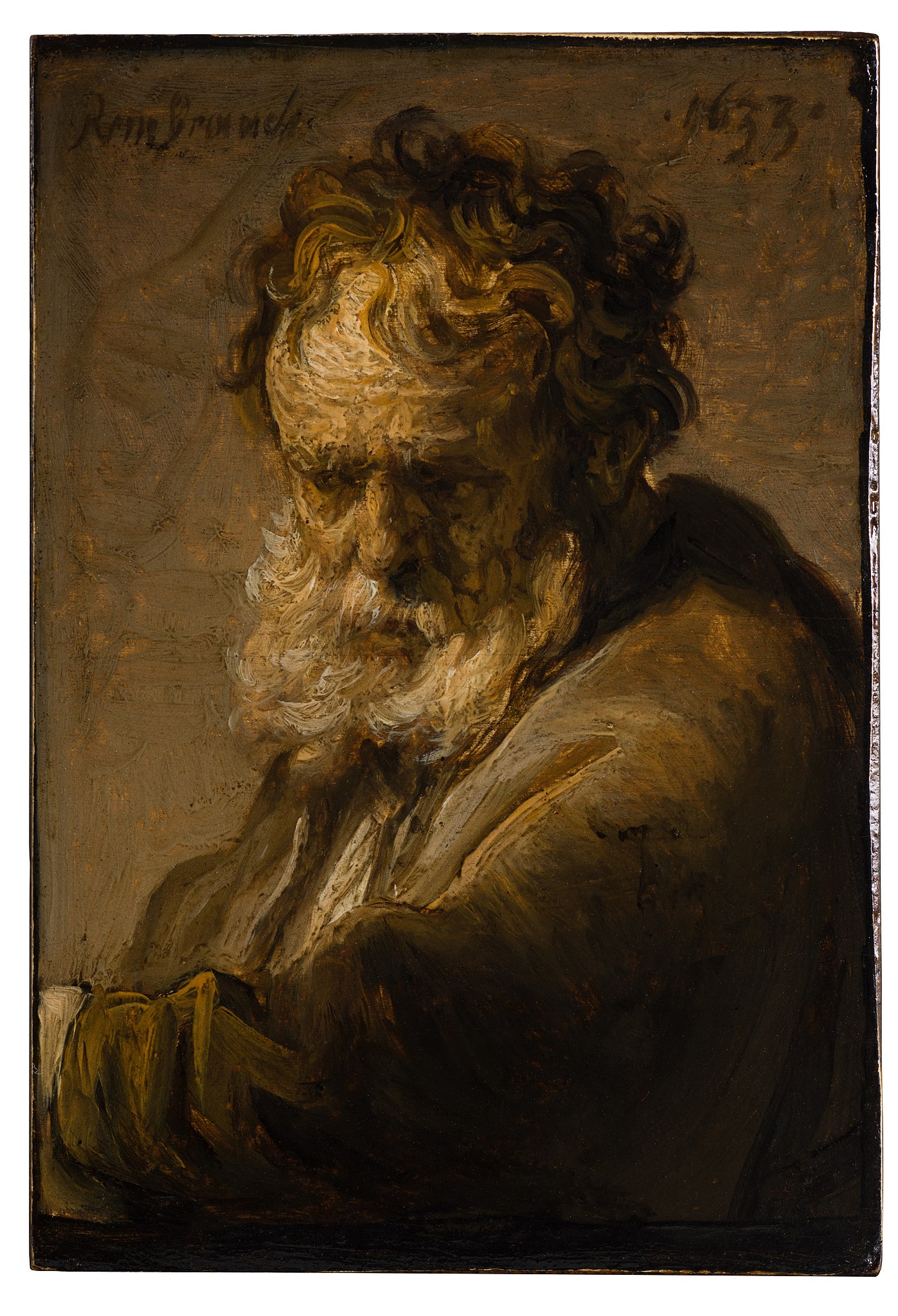

“Up close, it almost looks like Van Gogh,” Boelens notes of Bust of a Bearded Old Man (1633), a painting no larger than a playing card. Just as the eye assembles the checkered images of Impressionist paintings, so too do we turn Rembrandt’s patchwork of shape and color into a more precise, cohesive whole. “By doing so, we become participants in the artwork,” Boelens adds.

For a while, Rembrandt’s apprentices followed his example. In Aert de Gelder’s Christ on the Mount of Olives (1715), the last of Rembrandt’s pupils incorporated not just his trademark use of chiaroscuro – the stark contrast between light and dark,