Liquid-fueled rocket engines operate by flowing fuel and oxidizer into a combustion chamber at high pressure in order to eject mass out of the rocket nozzle at high velocities. While there exist many ways for these propellants to be mixed (called engine cycles), they all have one major technical hurdle: how does a rocket engine get up to operational pressures? Furthermore, how is this done in the zero-normal force environment of orbit?

Starting a liquid rocket engine is a very complex sequence of managing pressures and temperatures throughout all of the valves and pumps in the engine, where the smallest of errors leads to the engine experiencing a RUD (rapid, unscheduled disassembly).

Starting a Solid Rocket Booster/Motor

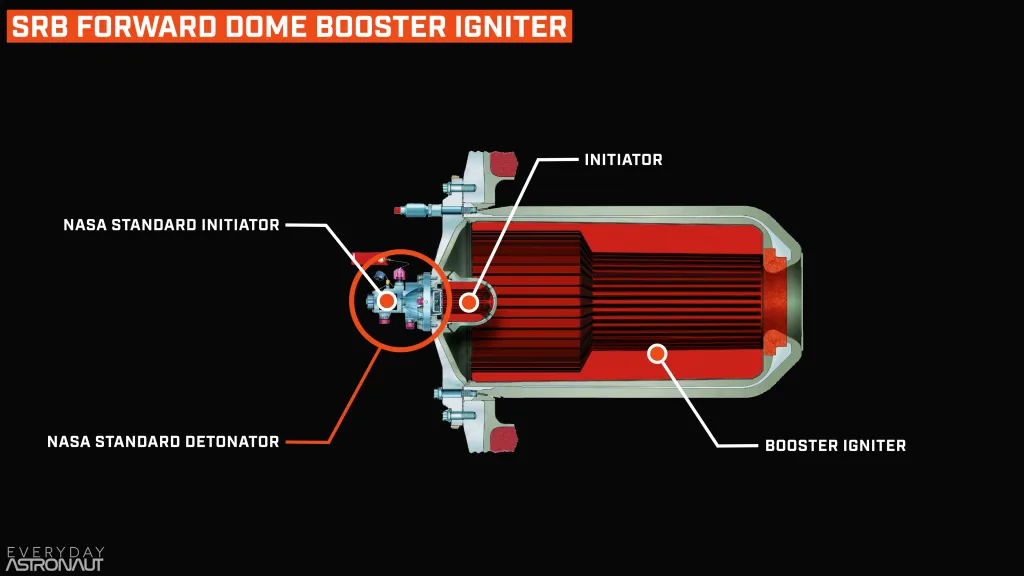

By far the simplest rocket engine to start are solid rocket boosters, which are widely used in the industry; most notably, NASA’s Space Launch System and Space Transport System (the space shuttle) have used two massive solid rocket boosters. Since solid propellant is fuel and oxidizer mixed into a solid sludge, to light a solid engine a small amount of energy is needed to start combustion.

To start these SRBs, a signal is sent to two completely redundant NSDs to ensure both boosters light properly. The NSDs burst a thin seal, which then ignites a pyrotechnic booster charge. That booster charge then ignites propellant in an igniter initiator, which is what fires down the entire length of the solid rocket motor, lighting the entire surface of the core of the booster simultaneously.

This highlights the entire benefit of solids: they are super simple and super reliable. This comes with disadvantages, such as not being able to shut them down and lower performance than liquid rocket engines.

Igniting Liquid Rocket Engines

Preconditioning The Engine

Before a liquid-fueled rocket engine is able to start, the engine must be prepared for the extremely low temperatures it’s about to experience from the liquid propellants. As discussed here, not only do orbital rocket engines run propellant through the walls of the engine to keep the combustion chamber from melting, but the pumps themselves flow upward of thousands of liters per second of cryogenic propellants, which makes the metals, valves, and bearing brittle and prone to failure. This is especially true for engines that run on RP-1 and liquid oxygen (called kerolox) and especially true for liquid hydrogen and oxygen (called hydrolox), or liquid methane and oxygen (called methalox).

The majority of liquid-fueled rockets are one of the aforementioned propellant combinations. Examples of RP-1 and LOx are SpaceX’s Merlin, the Saturn V’s mighty F1 engine, Rocket Lab’s Rutherford, the Atlas V’s RD-180, the Soyuz’s RD-107 and RD-108 engines, Firefly’s Reaver and Lightning engines, and so on.

Slowly the industry has been moving toward the next-generation rocket propellant: methalox. As previously discussed, CH4 is a good middle ground between keralox and hydrolox, generating a moderate amount of thrust at a moderate specific impulse. The majority of upcoming rockets engines use methalox, including SpaceX’s Raptor, Blue Origins BE-4 (which will fly both on ULA’s Vulcan rocket and Blue Origin’s New Glenn), Relativity’s Aeon engine, Zhuque-2’s TQ-12, and the Archimedes engine on Rocket Lab’s Neutron.

<br />

” data-image-description=”” data-image-meta=”{“aperture”:”0″,”credit”:””,”camera”:””,”caption”:””,”created_timestamp”:”0″,”copyright”:””,”focal_length”:”0″,”iso”:”0″,”shutter_speed”:”0″,”title”:””,”orientation”:”0″}” data-image-title=”Starting-Rocket.00_06_39_24.Still010″ data-large-file=”https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Starting-Rocket.00_06_39_24.Still010-1024×576.jpg” data-lazy-sizes=”(max-width: 1024px) 100vw, 1024px” data-lazy-src=”https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Starting-Rocket.00_06_39_24.Still010-1024×576.jpg?is-pending-load=1″ data-lazy-srcset=”https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Starting-Rocket.00_06_39_24.Still010-1024×576.jpg 1024w, https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Starting-Rocket.00_06_39_24.Still010-300×169.jpg 300w, https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Starting-Rocket.00_06_39_24.Still010-768×432.jpg 768w, https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Starting-Rocket.00_06_39_24.Still010-1536×864.jpg 1536w, https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Starting-Rocket.00_06_39_24.Still010-2048×1152.jpg 2048w, https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Starting-Rocket.00_06_39_24.Still010-1200×675.jpg 1200w, https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Starting-Rocket.00_06_39_24.Still010-380×214.jpg 380w, https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Starting-Rocket.00_06_39_24.Still010-800×450.jpg 800w, https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Starting-Rocket.00_06_39_24.Still010-1160×653.jpg 1160w, https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Starting-Rocket.00_06_39_24.Still010.jpg 3840w” data-medium-file=”https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Starting-Rocket.00_06_39_24.Still010-300×169.jpg” data-orig-file=”https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Starting-Rocket.00_06_39_24.Still010.jpg” data-orig-size=”3840,2160″ data-permalink=”https://everydayastronaut.com/how-to-start-a-rocket-engine/starting-rocket-00_06_39_24-still010/” decoding=”async” height=”576″ src=”https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Starting-Rocket.00_06_39_24.Still010-1024×576.jpg” width=”1024″><figcaption>A scale of propellant temperatures. (Credit: Everyday Astronaut)</figcaption></figure>

</div>

<p>Taking temperatures to extremely low depths, many rocket engines use hydrolox. These engines are extraordinarily hard to start due to hydrogen’s boiling point being -252°C and its very low density. Some of these engines include the RS-25 on the Space Shuttle and SLS, the RL-10 variants that fly on Atlas, Delta, SLS, and soon Vulcan, the J-2 on the Saturn V, the RD-0120s on Energia, or the RS-68A on the Delta. Additionally, Stoke Space’s upcoming engine will also run on hydrolox.</p>

<p>However, before an engine can be conditioned by flowing propellants through the engine, it must be purged. This process generally involves blasting gaseous nitrogen throughout the engine, purging the lines eliminating air pockets and moisture. This is important as any water vapor in the lines before cryogens are introduced will freeze, causing damage to the engine, potentially clogging orifices and damaging sealing surfaces.</p>

<div>

<figure><img alt=) Chill Down

Chill Down

Chill down starts at vastly different times depending on the engine. For instance, the nine Merlin engines on the Falcon 9 begin chill-down at T-7 minutes, whereas the RS-25 on SLS starts chilling down hours before launch. This event is usually paired with a callout on the nets with “engine cool-down” or “engine chill-down.”

Closer to T0, the rocket will transition from the inert gas and will begin to flow some of the propellants through the system at a low flow rate, where it will start to thermal condition the engine to get it to the cryogenic temperatures. This process is surprisingly easy, due to the rocket’s tanks storing propellant at relatively high pressure, usually three-to-six bars. Because of this, some valves can just be opened, and the pressure from the tanks will ensure propellant flows from the tanks through the engine.

Depending on the engine, the rocket, and the ground systems, the propellant that has gone through the engine may be vented into the air. This is especially true with liquid oxygen, which poses no risk when being vented into the atmosphere. However, for CH4 and H2, it will generally be either cooled down again into a liquid or burned in a flare stack, to reduce their impacts on the atmosphere.

Not only is the engine chilled to protect itself from the cold propellant, it’s also done to protect the propellant from the warm engine. If the propellant boils before reaching the impellers in the pumps, it can cause cavitation (small bubbles in the liquid). These bubbles can chip away material from the pumps and damage the blades. SpaceX CEO and CTO Elon Musk talked about this in Everyday Astronaut’s tour of Starbase:

But, not only can these bubbles damage the pumps by chipping at them, but they can also cause the pumps to overspeed, meaning they deliver the incorrect amount of propellant to the combustion chamber. This can cause the engine to burn at stoichiometric conditions, which releases the most heat to the engine, damaging or even destroying it.

This chill-down process is absolutely vital. In fact, SLS’ launch attempt in August of 2022 was scrubbed for this reason; engine 3’s temperature sensor wasn’t showing that the engine had chilled down to the required temperatures, scrubbing the launch for the day. It later turned out that this data was due to a faulty sensor and not the engine not being at operational temperatures.

Exceptions

This all said, there are exceptions to the chill-down process: hypergolics. Hypergolic propellants are those that combust upon contact with each other. The hypergolics that are used in rocketry have a high boiling point, meaning that they can be kept at room temperature. Because of this, the engines do not need to be chilled down.

Obviously, this has its advantages for many intercontinental ballistic missiles and their derived rockets, which generally run on hydrazine. The fuel can be either unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine, hydrazine, or monomethylhydrazine with the oxidizer being nitrogen tetroxide.

The US’ use of hypergolic-based rockets has been limited. The LR87 on Titan II and the AJ-10 on Delta II’s upper stage were hypergolic. That said, hyperbolic rockets were very popular in the Soviet Union, which can be seen in this article. Additionally, many of China’s launch vehicles run on hypergolics, but they are slowly shifting away from this.

<br />

” data-image-description=”” data-image-meta=”{“aperture”:”0″,”credit”:””,”camera”:””,”caption”:””,”created_timestamp”:”0″,”copyright”:””,”focal_length”:”0″,”iso”:”0″,”shutter_speed”:”0″,”title”:””,”orientation”:”0″}” data-image-title=”Hypergolics storage” data-large-file=”https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Hypergolics-storage-1024×576.jpg” data-lazy-sizes=”(max-width: 1024px) 100vw, 1024px” data-lazy-src=”https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Hypergolics-storage-1024×576.jpg?is-pending-load=1″ data-lazy-srcset=”https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Hypergolics-storage-1024×576.jpg 1024w, https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Hypergolics-storage-300×169.jpg 300w, https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Hypergolics-storage-768×432.jpg 768w, https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Hypergolics-storage-1536×864.jpg 1536w, https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Hypergolics-storage-1200×675.jpg 1200w, https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Hypergolics-storage-380×214.jpg 380w, https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Hypergolics-storage-800×450.jpg 800w, https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Hypergolics-storage-1160×653.jpg 1160w, https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Hypergolics-storage.jpg 1920w” data-medium-file=”https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Hypergolics-storage-300×169.jpg” data-orig-file=”https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Hypergolics-storage.jpg” data-orig-size=”1920,1080″ data-permalink=”https://everydayastronaut.com/hypergolics-storage/” decoding=”async” height=”576″ src=”https://everydayastronaut.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Hypergolics-storage-1024×576.jpg” width=”1024″><figcaption>Hypergolic propellants stored at room temperature. (Credit: NASA / Everyday Astronaut)</figcaption></figure>

</div>

<h3 id=) Spin Up

Spin Up

After the engine has been pre-conditioned for starting, the next goal is to spin up the pumps. To do this, engineers must take into account one of the most fundamental laws of the universe: pressure flows from high pressure to low pressure. In order to ensure that a flame is not sent backwards through the system, which would lead to a catastrophic failure, the pressure upstream an engine must be very high. In fact, for some engines like SpaceX’s Raptor, pressures upstream can approach 1,000 bar!

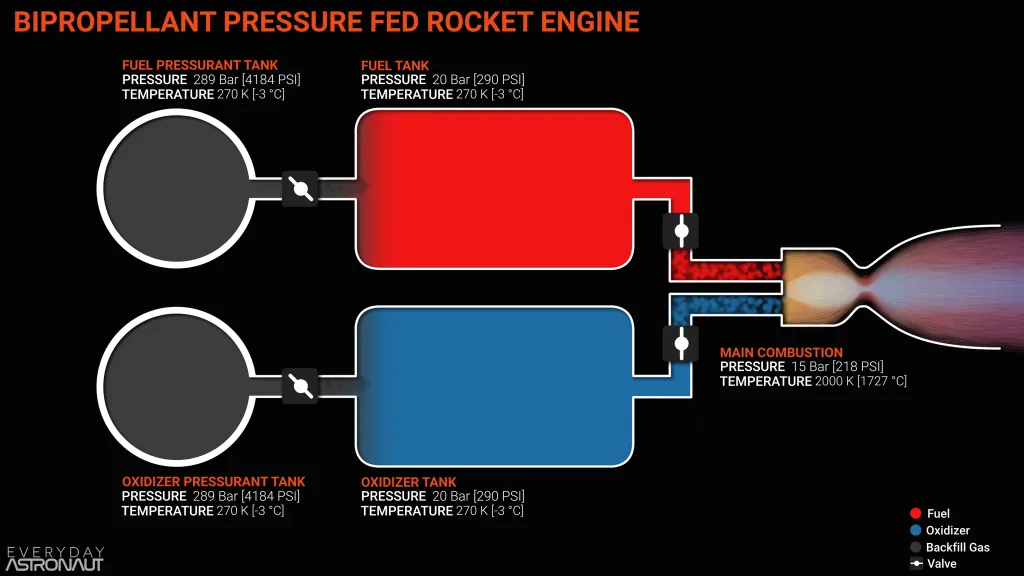

The simplest engine cycle to spin up is a pressure-fed engine. Because the propellant is already stored at high pressure, simply opening valves will allow propellants to flow into the combustion chamber at the necessary operating pressure.

This said, pressure-fed engines are not enough to get objects into orbit from the Earth’s surface. For this reason, high-power high-pressure engines are needed that have turbopumps. In most engines, the turbine has hundreds of thousands of horsepower from just one turbine. That turbine is of course spun by a gas generator or preburner, which is fed by the pumps. This creates a hard dynamic that the turbine must be spinning to get move propellants to the preburner/gas generator, but the preburner/gas generator must be burning to spin the turbine.

The simplest way of bypassing this, which is done by Rocket Lab’s Rutherford engine, is to use an electric motor to drive the turbine. Then, this is not a problem. But this is not feasible for larger engines, such as the RS-25, which needs 100,000 horsepower to spin its turbine when at full throttle.

What’s more, is the RS-25’s fuel preburner delivers 200 horsepower per kilogram, highlighting why electric motors would not be practical.

Spinning up a preburner/gas generator is generally done by using high-pressure gas to get the pumps spinning. This can either be supplied by an onboard system, like helium stored in COPVs, or by ground service equipment. Spinning up engines with GSE is advantageous since it removes mass and complexity from the rocket.

In either case, high-pressure helium or nitrogen is pumped into the gas generator/ preburner to get the turbine spinning at operational speeds. For a short period of time, the engine’s pumps are powered by what is basically a cold gas thruster, which is very inefficient. Alternatively, some engines use a little solid or hypergolic engine that acts as a gas generator for a small amount of time.

However, due to the low specific impulse of these systems, you don’t want to run the engine off this for any longer than necessary, so it’s only done until the engine can self-sustain combustion. This means that for engines that require multiple starts (such as engines on upper stages that may have to burn several times to reach a desired orbit or for a propulsive landing), the rocket must carry enough helium to spin up the engines.

Bootstrapping

However, there is another way of starting a rocket engine that doesn’t require a separate source to get the pumps up to speed. This process, called bootstrapping (or tank head / dead head starting) is where the engine carefully lights up using only tank pressure and energy stored in the thermal difference between the propellant and the engine. To do this, the preburner (powering the turbine) will begin to spin up due to hydrogen flowing through the preburner and boiling off. This raises the pressure, starting to spin the turbine. Then a very delicate dance takes place, as some oxygen is let in and the preburner lights. At first, the combustion is very weak, but as the pressure in the preburner rises, the pumps spin faster, providing more fuel to the preburners, causing the pressure to rise, spinning the pumps faster. This is done until the engine is at operational pressure.

This process is used on the RS-25 (both on the Space Shuttle and on SLS), wherein the RS-25, the high-pressure fuel turbopump must reach 4,600 RPM within 1.25 seconds for the engine to have enough propellant flow for ignition of the main combustion chamber (MCC). Additionally, Relativity has successfully bootstrapped the first stage of their Terran 1 vehicle, and Firefly’s ex-CEO Tom Markusic mentioned in an interview with Everyday Astronaut that firefly was looking into trying to bootstrap Alpha’s second stage.

Deadhead starting is an extremely complex process due to the precise control needed. But this is made even more complex given that when an engine is starting up it is in a transient: the time in b