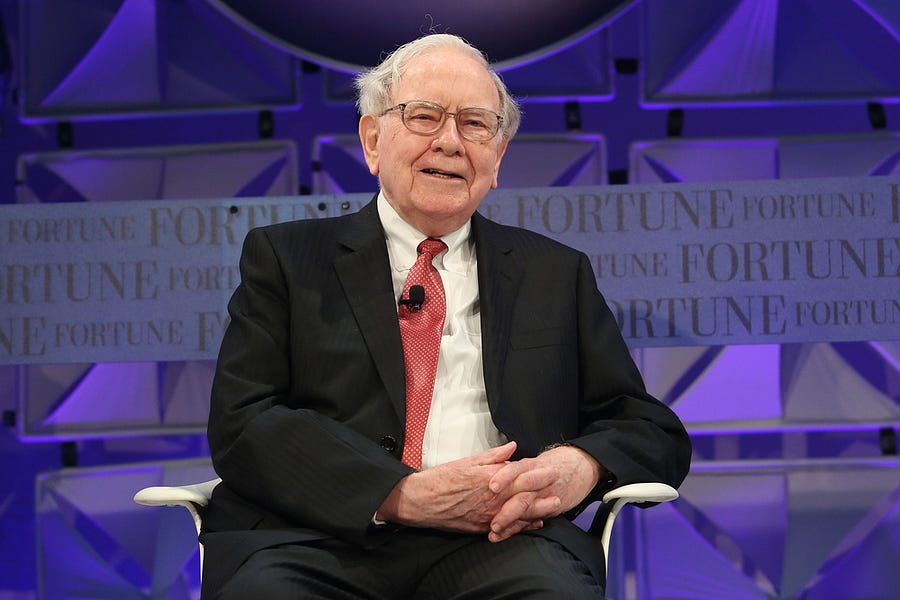

Use Warren Buffett’s 3 Principles:

1. Only invest in companies that you understand, and where you can reasonably estimate the future economics 10+ years out. That should eliminate most companies for most people.

Here is an example of one such company for me. A glass bottle manufacturer. The product has been around for a very long time. Demand is stable. There are substitutes, such as aluminum cans and plastic bottles, but share shifts are very slow. Capacity takes a long time to bring on stream. It’s a small portion of the total cost of the end product but important to how the end consumer perceives it. It is unlikely that a new alternative will be invented any time soon, and even if it were, there are both perceived and real switching costs.

Here are examples of companies that don’t pass this test for me: An early-stage biotech company working on a new drug. An electric vehicle manufacturer that has a strong brand but with a lot of competition and an industry with a history of many an exciting company having fallen by the wayside. A commodity producer whose long-term economics are dependent on the price of a commodity that I can’t confidently estimate.

The specifics aren’t as important as that you are comfortable with the answer. You might be quite happy estimating the economics of a company that I or someone else might pass on. As long as your confidence is based on insight and an honest self-assessment rather than on hubris, that’s totally fine.

2. Feel comfortable doing nothing most of the time. Good ideas are rare. The math of waiting is very forgiving – you can get 0% for a while and still have a good long-term rate of return as long as you have high returns when you do invest. On the other hand, it’s hard to have a good rate of return if you have large losses.

Let’s say that you have two choices. You can earn 0% on your money for 3 years, after which you are going to invest it at a 15% annualized rate of return. Or you can invest it right away at a 7% annual rate of return. The first choice is meant to represent you not being able to find a sufficiently good idea for the first 3 years of looking – a fairly unlikely, but possible, scenario if you know where and how to look.

You can of course disagree with the assumptions. A 15% rate of return with moderate risk isn’t easy to find, right? Well, that’s the point. Good things are worth the wait. On the other hand, the 7% assumption is somewhere in the neighborhood of what the current, early-2023 U.S. stock market seems to offer on a long-term basis. Some would argue that’s even an optimistic interpretation of the current price levels.

Also, if instead of needing 3 years to find a 15% annual return idea it takes you only 2, then the 10-year annual rate of return becomes 12%, a full 5% per year above settling for being invested in sub-par returning investments. That’s a more realistic amount of time needed to find a good investment, and so I will use that as Scenario 1 going forward.

Let me be clear: I am not advocating market timing. Market timing is when someone says something like “gee, I think the market will go down a lot this year, so I am going to sit on the sidelines.” This isn’t that – it’s absolute value investing, as opposed to relative value investing.

We are simply saying that we have a minimum hurdle rate that we require in order to invest. If an investment meets that hurdle rate as well as our qualitative requirements, then we invest, regardless of what the market may or may not do. If we don’t find enough ideas that meet our absolute return threshold, we wait until we do. So waiting or investing isn’t a function of our opinion about what stock prices will do, it’s a residual of our valuation discipline.

Let me add one more scenario. In this case, you start investing in a 7% annual rate of return investment and receive that return for the first 4 years. However, in year 5 something goes wrong and you end up with a big, 40%, loss. That, by the way, is not that different than what we saw some of the more, shall we say,